Lecture 4

Externalities

September 5, 2025

Externalities

What is an Externality?

- An externality is a side effect of a market transaction—positive or negative—that affects the well-being of people who are not directly involved as buyers or sellers.

- Negative externality: imposes costs on others (e.g., air pollution from autos).

- Positive externality: confers benefits on others (e.g., tree planting—amenity value, carbon uptake, habitat).

- Comprehensive analysis must account for all members of society (and possibly ecosystems), not only buyers and sellers.

Tip

Key idea: Markets maximize total surplus only when all marginal costs and benefits are internal to decision‑makers.

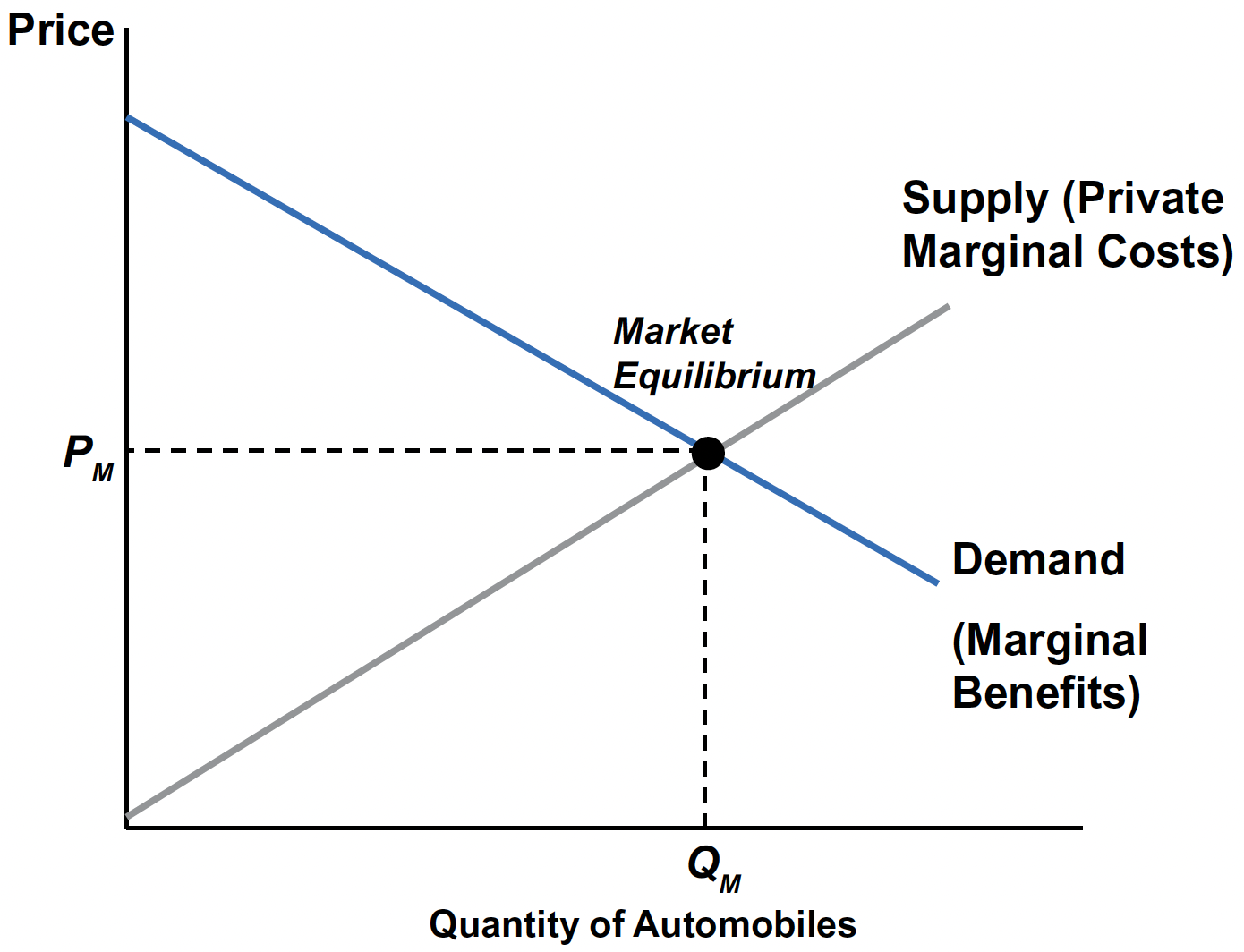

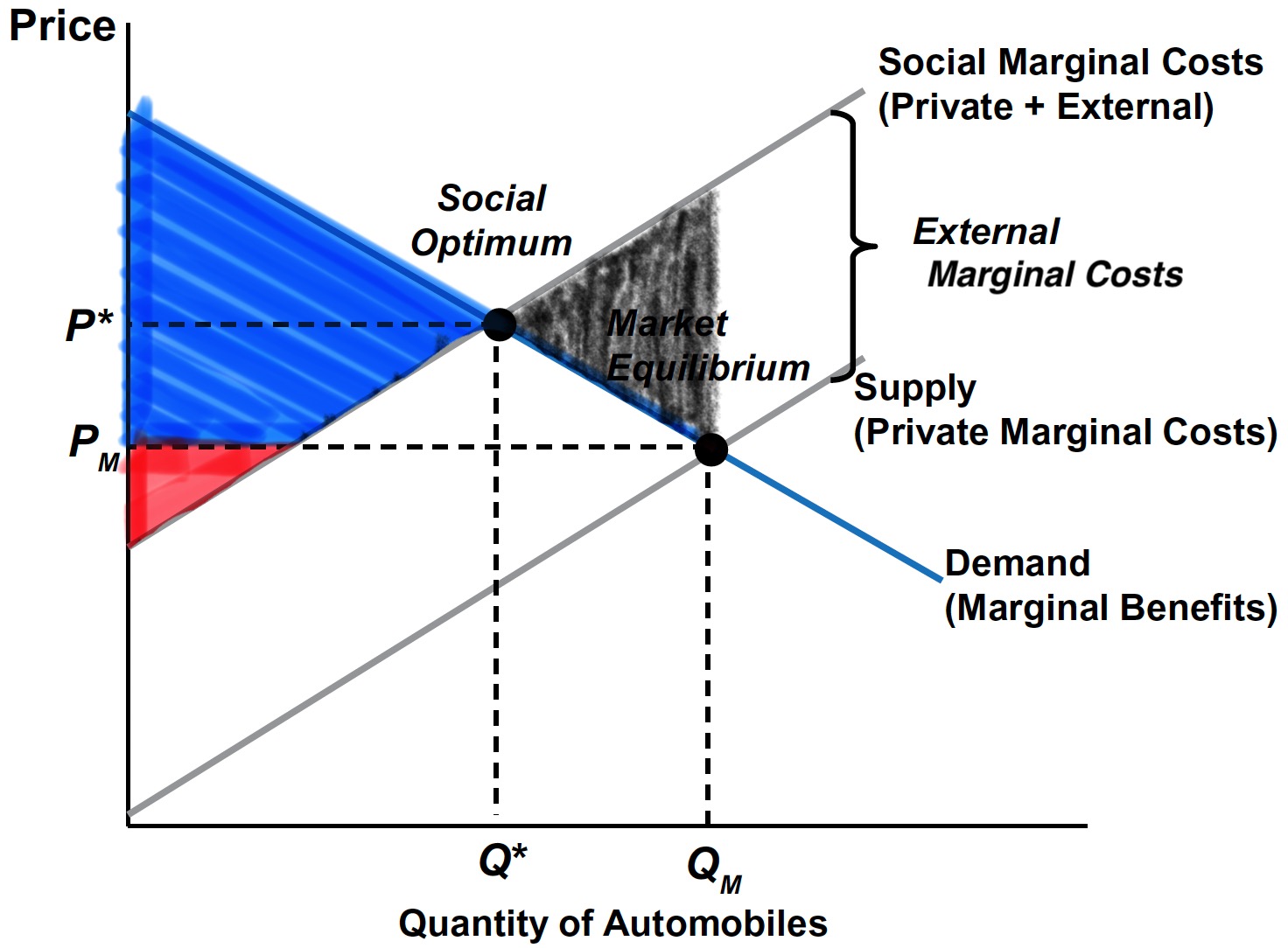

The Market for Automobiles

- Supply curve ≈ PMC: private marginal cost of producing one more unit (labor, materials, energy, etc.).

- Demand curve ≈ PMB: private marginal benefit (consumers’ willingness‑to‑pay for one more unit).

- Market equilibrium \((P_{M}, Q_{M})\) is efficient only if PMC = SMC and PMB = SMB (i.e., no externalities).

Accounting for Environmental Costs

- Auto production & use create multiple negative externalities: local/regional air pollution, CO₂, water contamination, toxic wastes, habitat loss, road salt runoff, congestion.

- These costs do not appear in the private supply curve; hence market overstates net social benefits at \((P_{M}, Q_{M})\).

- We must internalize external costs to evaluate the market’s true impact.

EPA Endangerment Finding on GHG Emissions

- Proposal Date: July 29, 2025 — EPA formally proposed rescinding the 2009 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Endangerment Finding (US EPA).

- Statutory Impact: Without the Endangerment Finding, EPA would lose authority under CAA §202(a) to regulate GHG emissions from motor vehicles (US EPA; Wikipedia).

- CAA §202(a) is the EPA’s authority to regulate tailpipe pollution from new vehicles when it threatens public health or welfare.

- Regulatory Effect: Proposal includes removal of GHG standards for light-, medium-, and heavy-duty vehicles and engines (US EPA).

- What Remains: Standards for criteria pollutants, toxic emissions, corporate average fuel economy (CAFE), and labeling will not be changed(US EPA).

EPA Endangerment Finding: Process & Reactions

- Public Hearing & Comment Period:

- Public hearings held August 19–21 (and possibly August 22), 2025.

- Comment deadline extended from September 15 to September 22, 2025 (Federal Register; Office of Advocacy; Holland & Knight).

- Public hearings held August 19–21 (and possibly August 22), 2025.

- Deregulatory Framing:

- Criticisms:

- Critics argue the rule ignores scientific consensus and is legally weak, potentially dismantling key rules and safeguards designed to protect against climate change (The Washington Post).

Valuing Damages

- Assign monetary values to external harms to build SMC:

- Direct costs (e.g., water treatment for contaminated sources).

- Health damages (medical expenses, morbidity, mortality risk).

- Aesthetic/amenity losses (visibility, recreation quality).

- Ecosystem impacts (biodiversity, habitat quality).

- If we assign no value, the market implicitly assigns zero—biasing decisions.

Warning

Valuation aggregates tangible and intangible impacts; precision is hard, but order‑of‑magnitude estimates guide better policy than zeros.

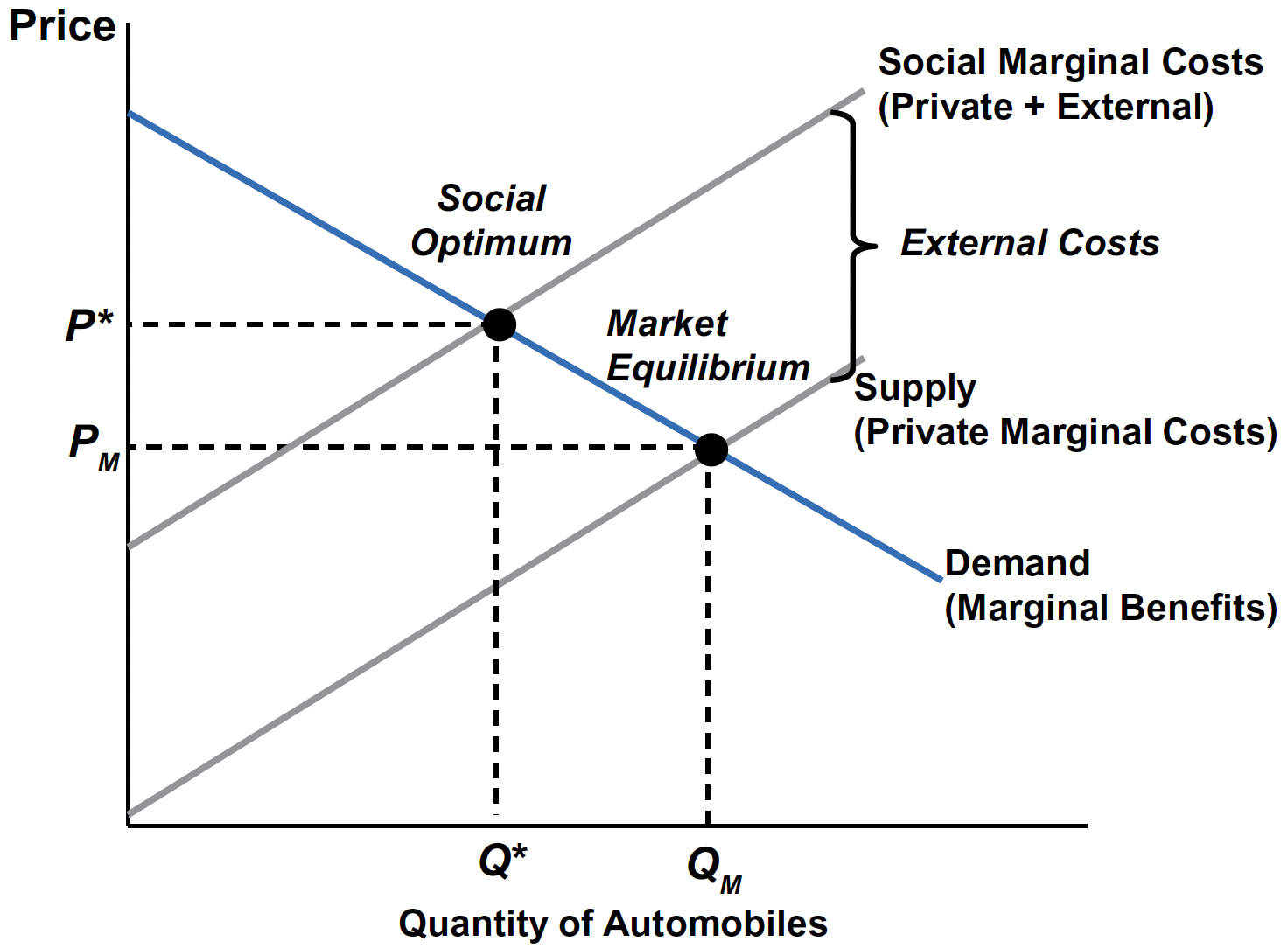

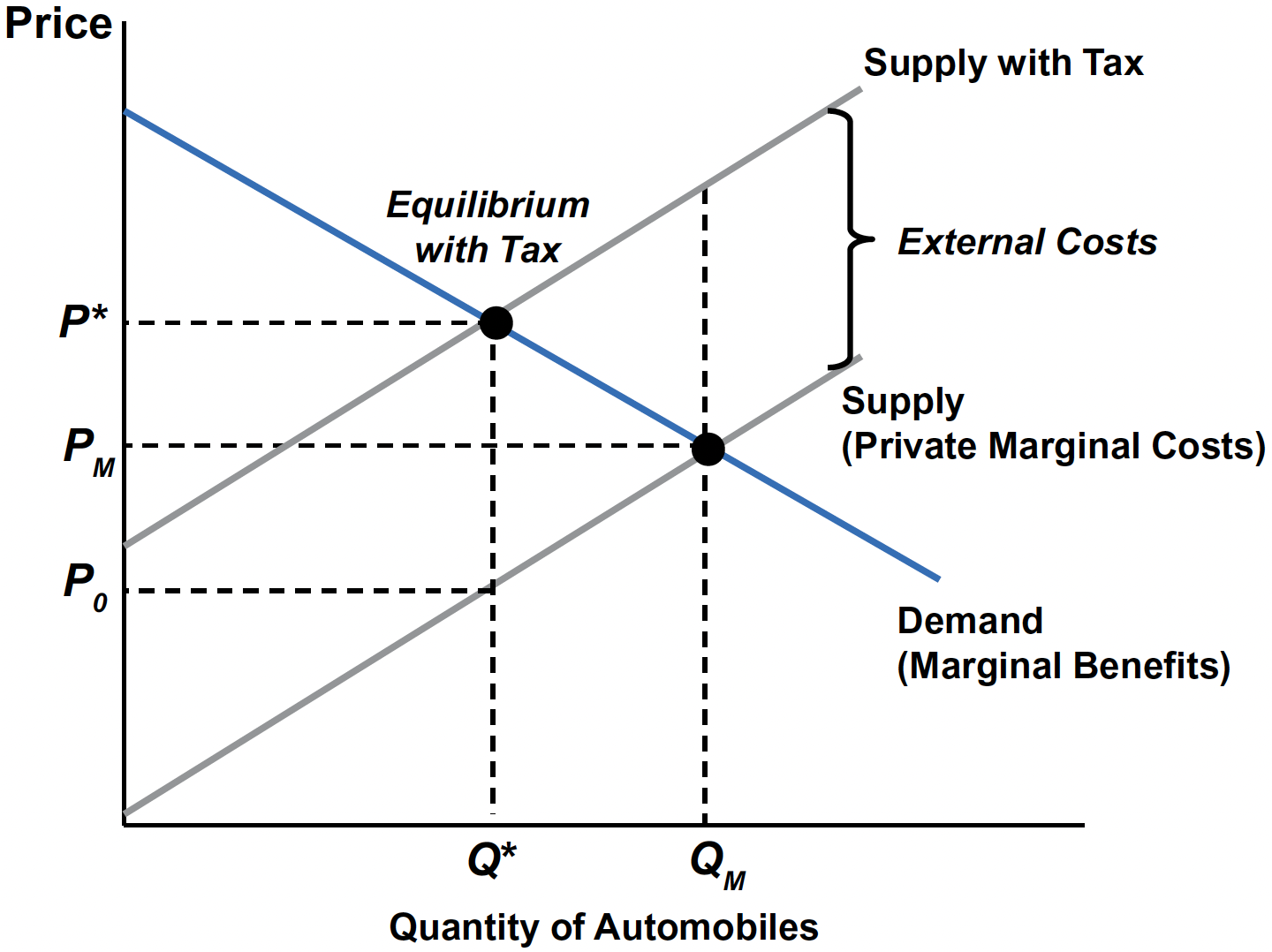

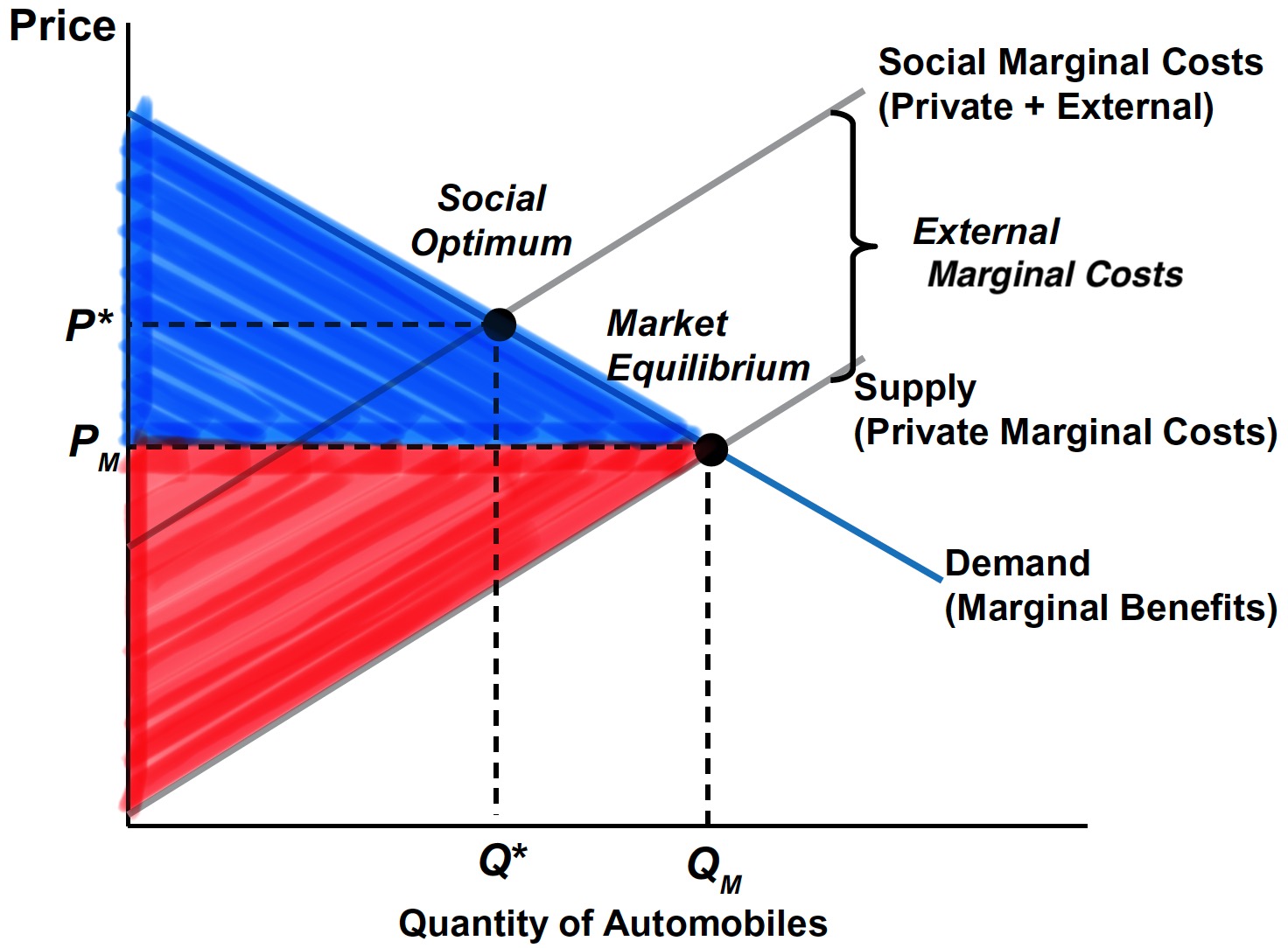

The Market for Automobiles with Negative Externalities

- SMC = PMC + EMC, where EMC is the external marginal cost.

- Typically, EMC rises with output when pollution/congestion intensify.

- SMC lies above PMC by the vertical distance equal to EMC.

Internalizing Environmental Costs

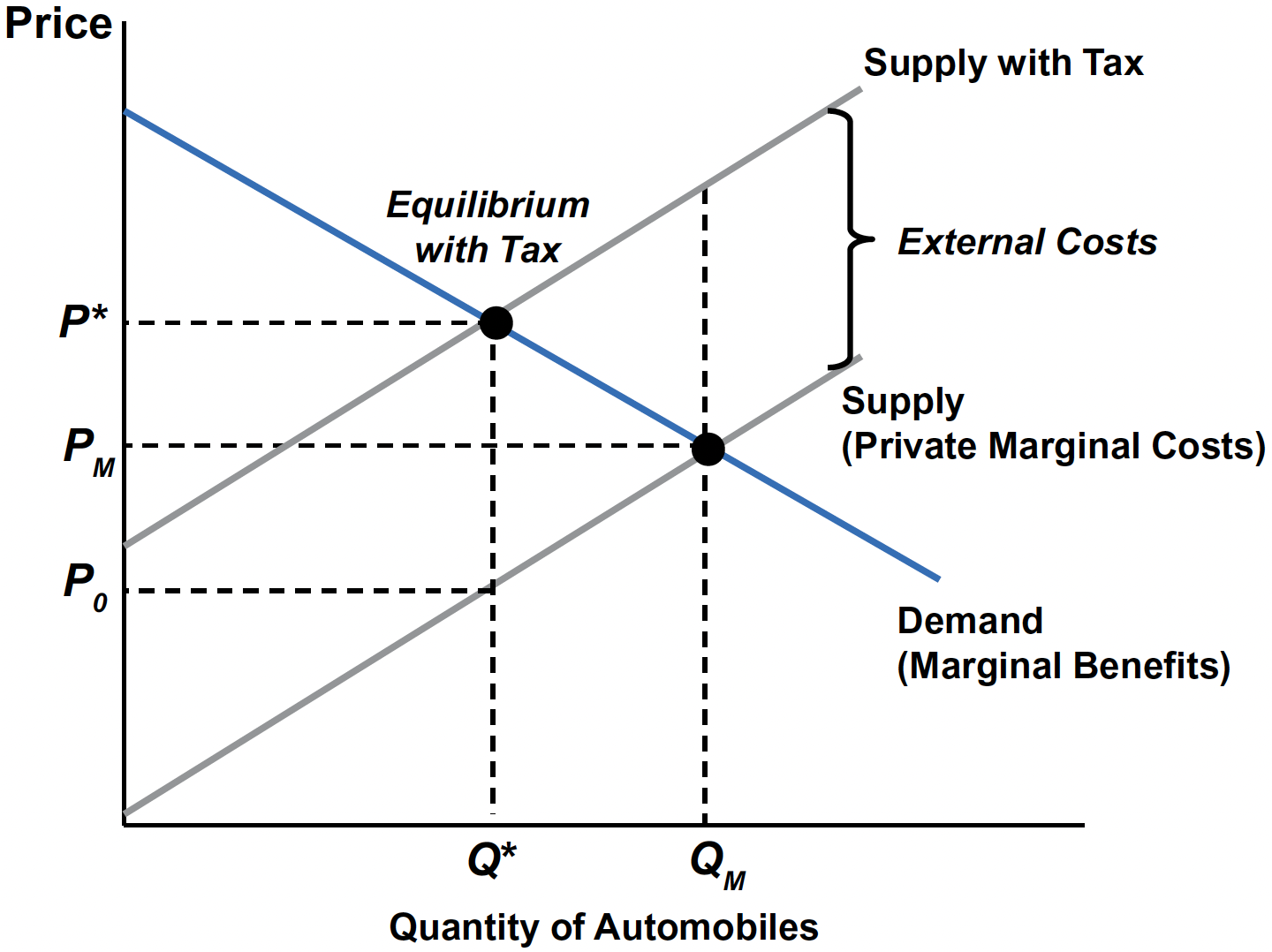

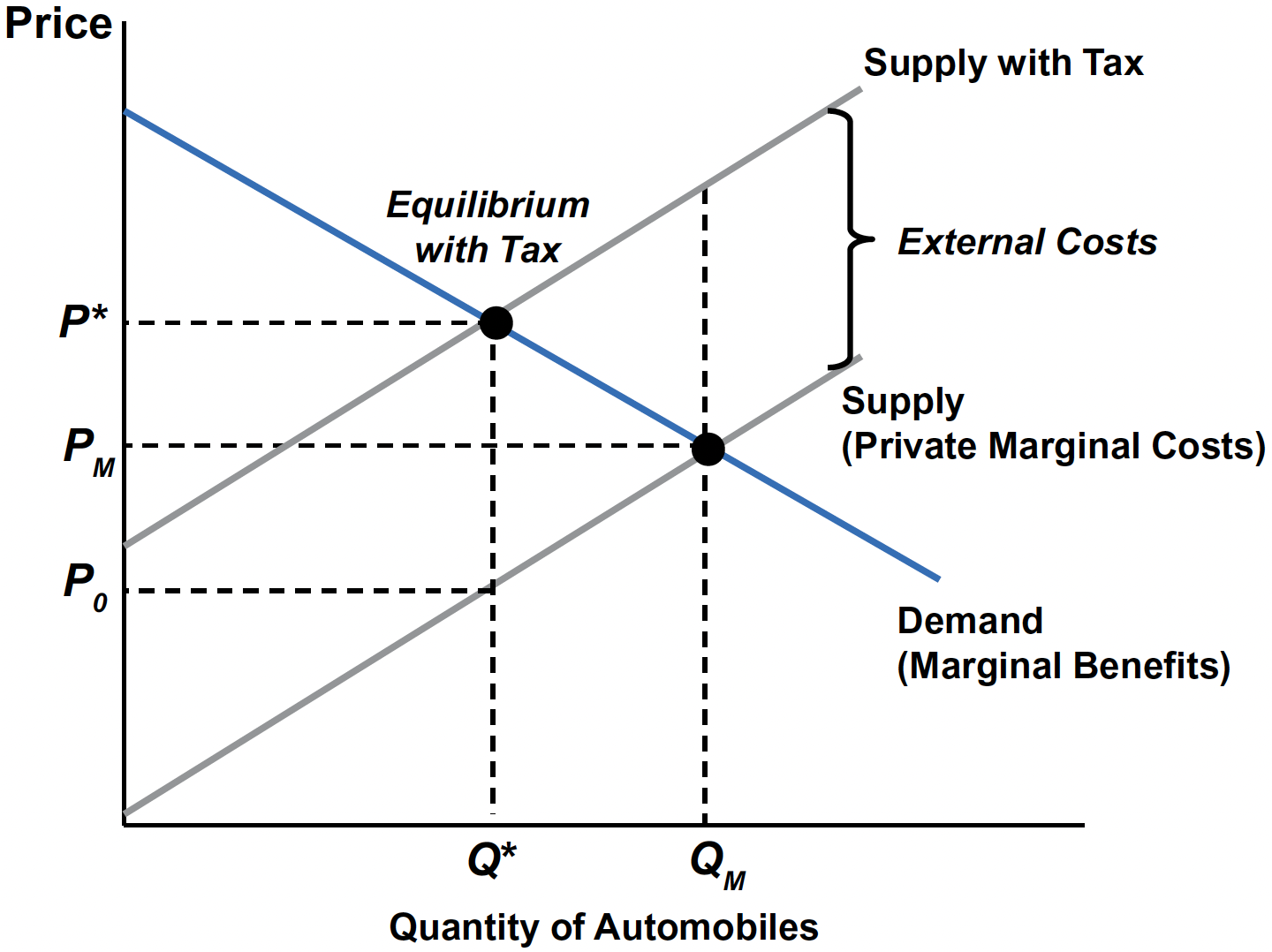

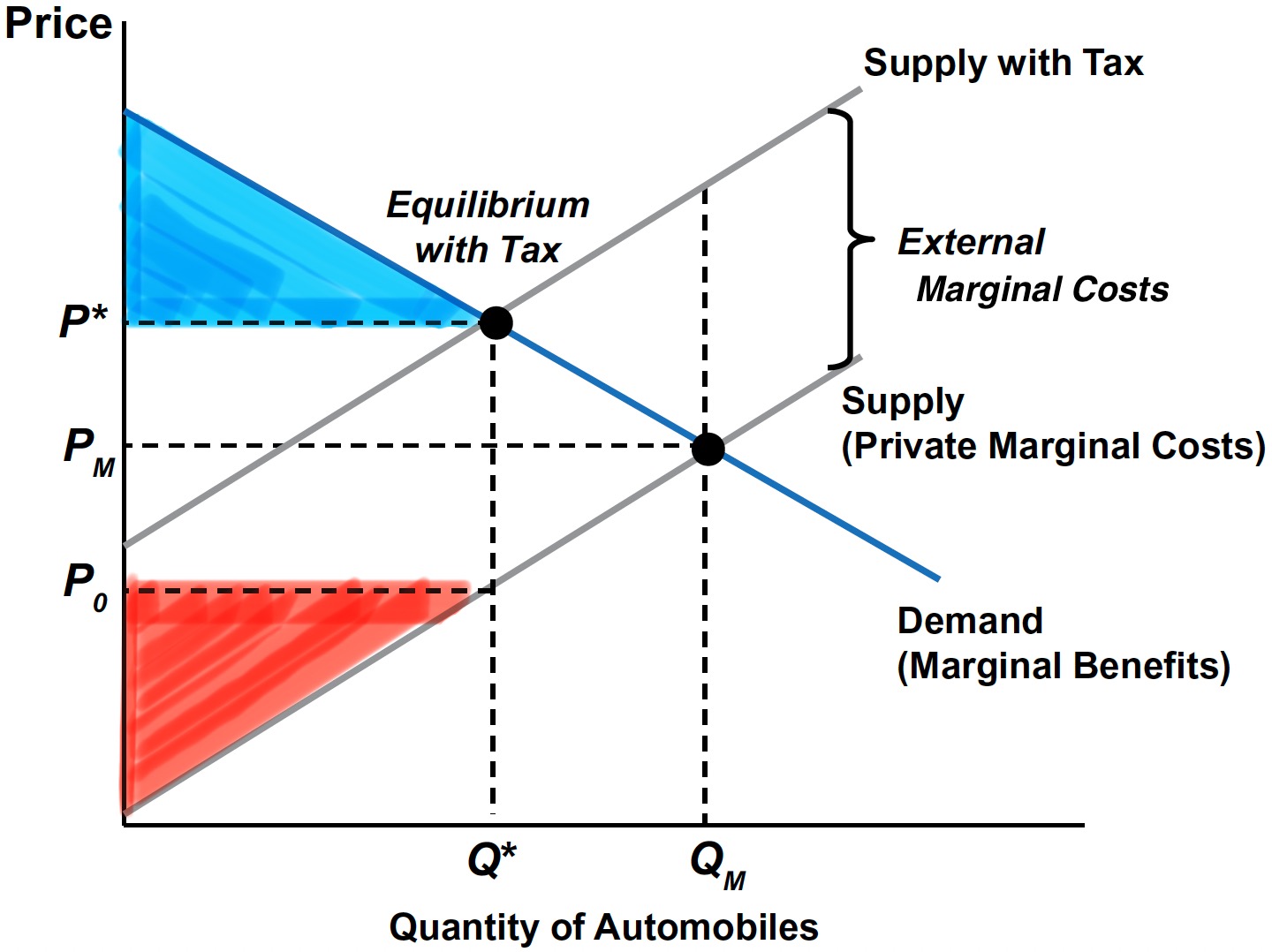

Fixing the Inefficiency: Pigovian Tax on Automobiles

- Market failure: Prices omit pollution damages ⇒ production beyond \(Q^{*}\) is socially undesirable.

- Goal: Get the price “right” by internalizing external costs so they enter consumer/producer decisions.

- Tool — Pigovian tax: A per-unit tax (t) on automobile production or emissions that makes

\[ \text{PMC} + t = \text{SMC} \quad \text{at } Q^{*}. \]- Reflects the Polluter Pays Principle (PPP): those causing pollution pay its external costs.

Automobile Market with Pigovian Tax

- Impose a per‑unit tax \(t\) equal to EMC at \(Q^{*}\).

- Effect: raises firms’ private marginal cost so the effective supply coincides with SMC.

- New equilibrium: \((P^{*}, Q^{*})\)—the socially efficient outcome.

- Set the right rate

- Target the per-unit external damage at \(Q^{*}\) so PMC + \(t\) = SMC.

Economic Tax Incidence & Elasticities

Note

A price elasticity of demand/supply measures how responsive the quantity demanded/supplied are to price changes.

An inelastic demand/supply ⇒ quantity changes little for a given price change.

- The more steeper, the less elastic.

- Consumer incidence: the amount of the tax revenue paid by consumers

- Producer incidence: the amount of the tax revenue paid by producers

Who Pays? Economic Incidence & Elasticities

- Who pays more?

- The less elastic (steeper) side of the market bears more of the tax.

- The less elastic (steeper) side of the market bears more of the tax.

- The claim “firms pass it all on” is generally false; division is empirical and depends on elasticities.

Distributional Concerns

Regressivity: Energy/fuel taxes can burden lower-income households (higher budget share on energy).

How to offset (Revenue recycling):

- Lump-sum dividends (“carbon cash-back”).

- Refundable credits (e.g., energy affordability credit, EITC (earned income tax credits) top-ups).

- Targeted transfers (rural mileage, extreme-climate heating, heating-oil users).

- Fixed bill credits / lifeline blocks for essential usage (avoid broad per-unit discounts).

- Just-transition support for affected workers/communities.

Design notes: Preserve price signals (don’t lower per-unit energy prices), make benefits visible, and address equity/political feasibility

Don’t tax everything

- Estimating the “right” tax requires economics + science.

- For small externalities, the revenue may not justify measurement + admin costs.

- Example: “shirts” would imply product-by-product rates (cotton vs. synthetics, dye processes, organic vs. recycled) → monumental complexity.

Go upstream (tax near resource extraction)

- Levy at raw inputs (e.g., crude oil, cotton, ores, toxic chemicals) so costs ripple through prices in proportion to input intensity.

- Focus on materials with widespread ecological damage (e.g., fossil fuels, key minerals, toxics).

- Benefits: far fewer tax points, lower admin burden, avoids bespoke rates on countless final goods.

Beyond Taxes: Standards & Mandates

- Performance/tech standards (e.g., fuel-efficiency rules) and mandated controls (e.g., catalytic converters) can cut emissions without directly pricing each unit.

- Standards often raise upfront/capital costs, so that prices can rise (resemble a tax), while energy-efficient equipment uses less fuel/power, so lifetime bills may fall.

- Useful where damage estimates are uncertain, admin is hard, or health/ecological thresholds justify minimum standards alongside prices.

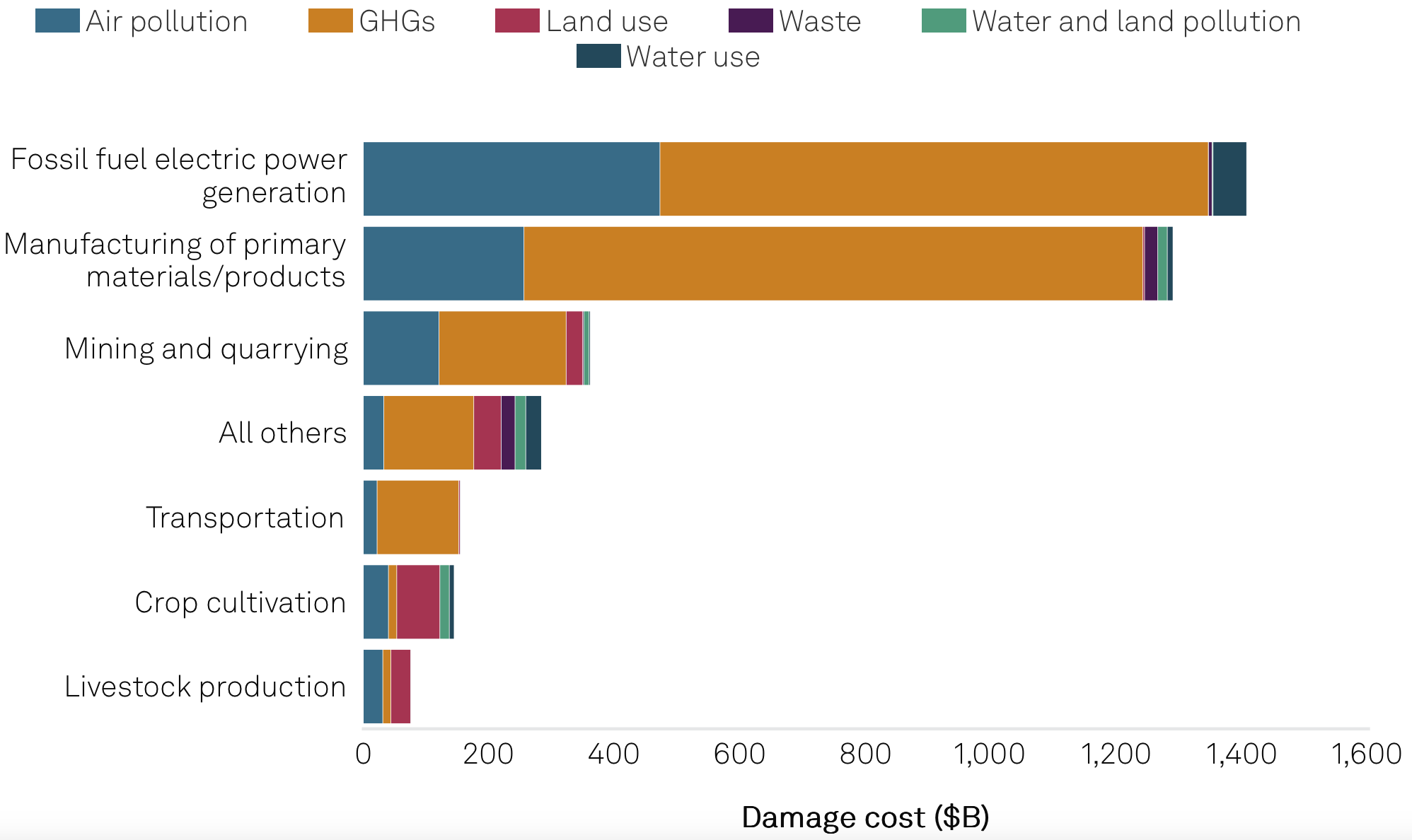

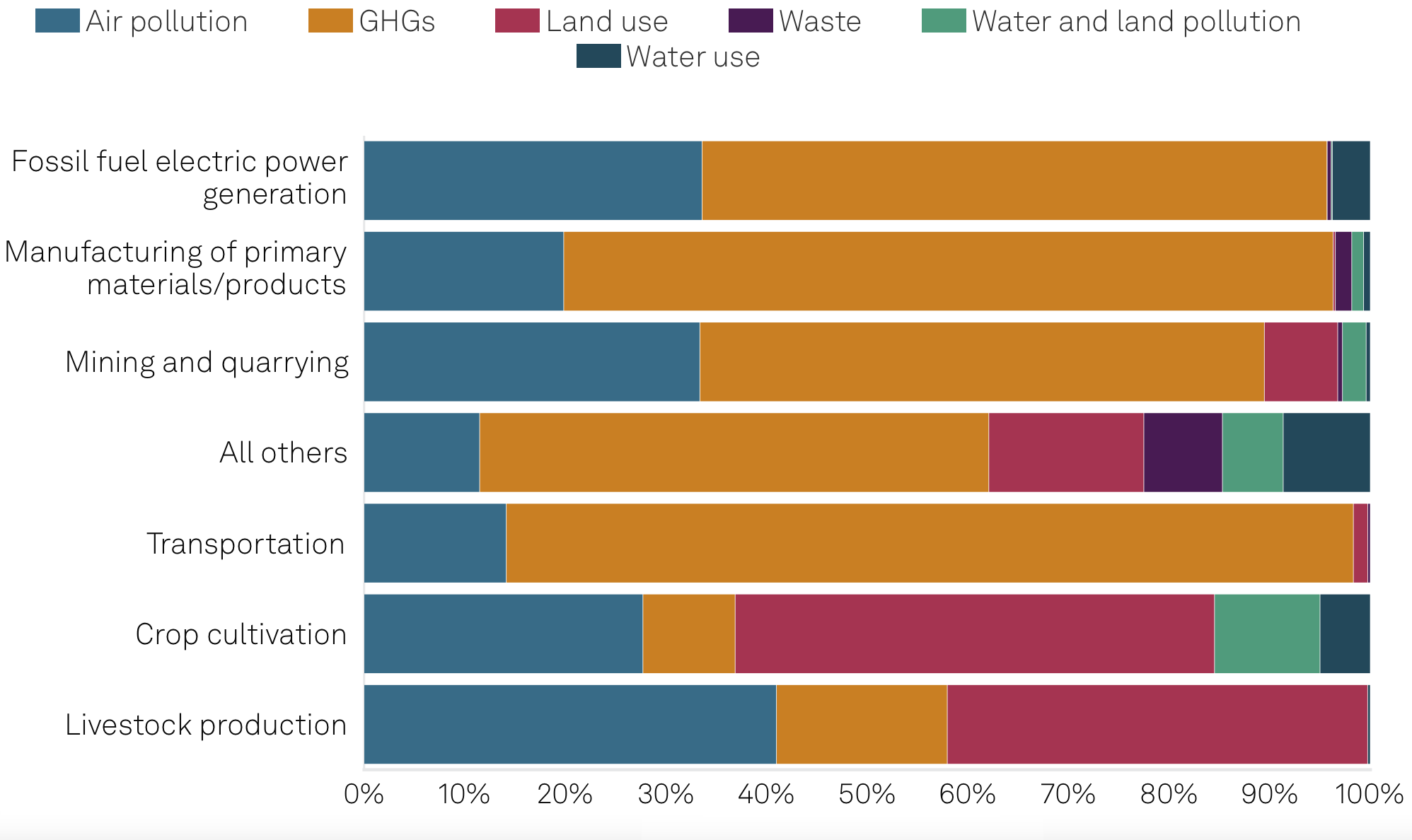

The Top Externalities of the Global Market

Environmental damage costs generated by companies in the S&P Global Broad Market Index by sector group in 2021.

The Top Externalities of the Global Market

Source: S&P Global Sustainable1.

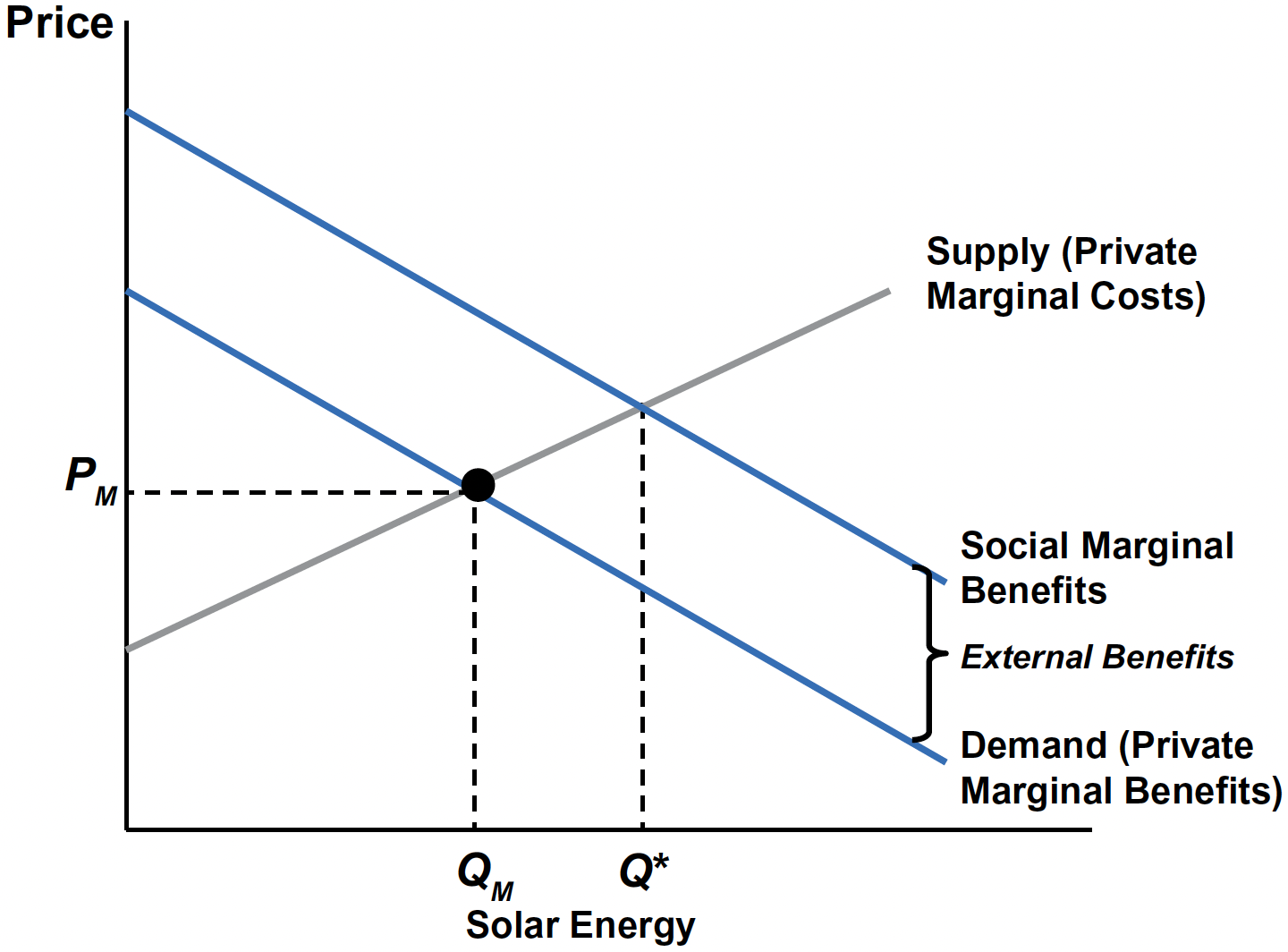

Positive Externalities

Positive Externalities: Market Outcome & Policy

Examples: solar panels (emissions reductions), vaccinations, R&D spillovers, urban trees.

In an unregulated market, beneficial spillovers aren’t rewarded → underproduction:

PMB < SMB ⇒ \(Q_{M}\) < \(Q^{*}\) → welfare loss.

- Goal: internalize social benefits to reach the efficient level \(Q^{*}\)

- Solar PV example:

- Neighbors learn from one household’s installation/operation experience.

- If one home’s solar panels make more electricity than that home uses during the day, the extra can flow onto the neighborhood.

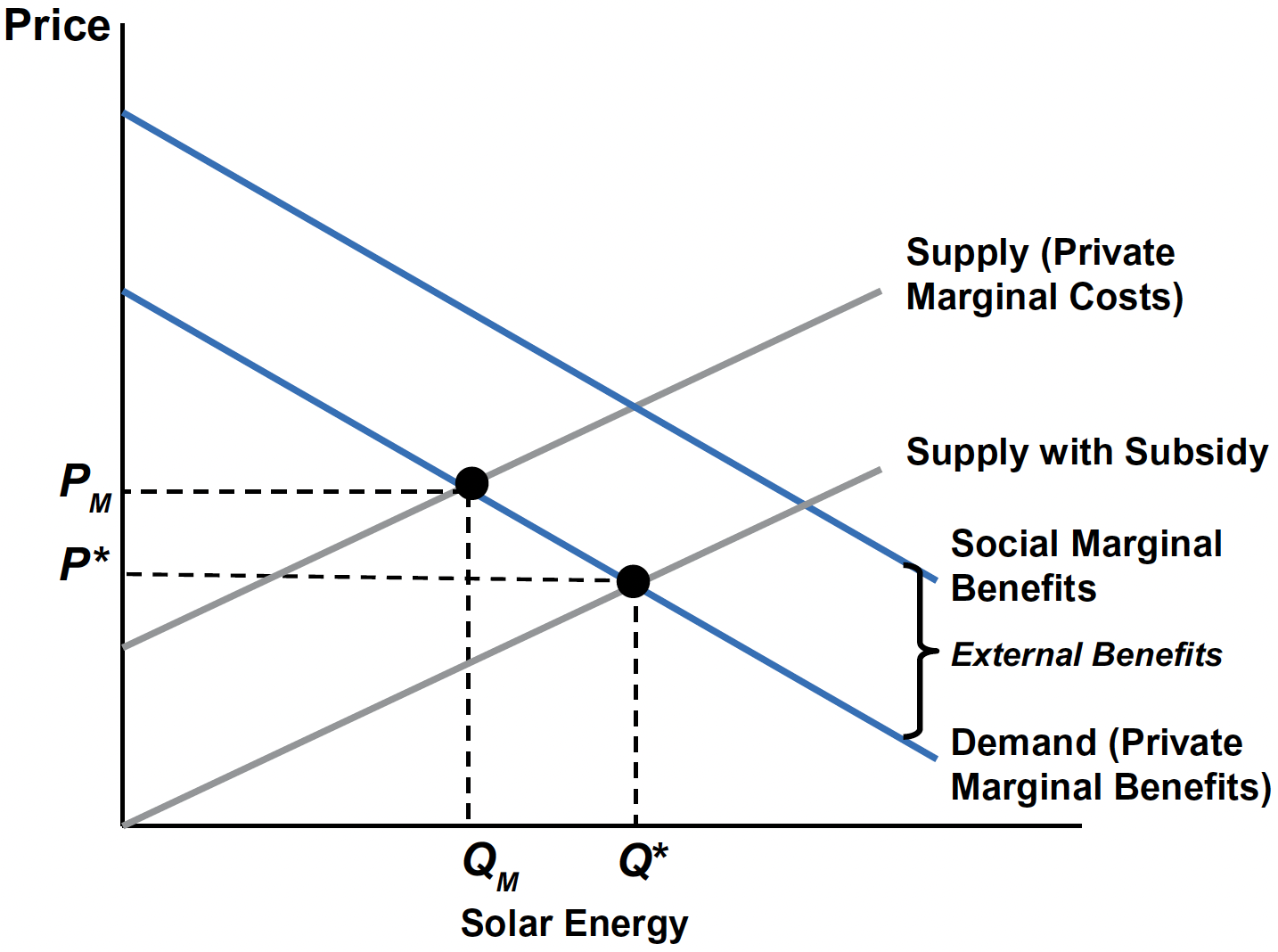

The Market for Solar Energy

- SMB = PMB + EMB, where EMB is external marginal benefit.

The Market for Solar Energy with a Subsidy

- A producer subsidy of \(s\) per unit lowers effective marginal cost (downward supply shift).

- A consumer subsidy (e.g., tax credit) raises effective willingness‑to‑pay (upward demand shift).

- Correct subsidy aligns the market with \(Q^{*}\) where SMC = SMB.

Welfare Analysis of Externalities

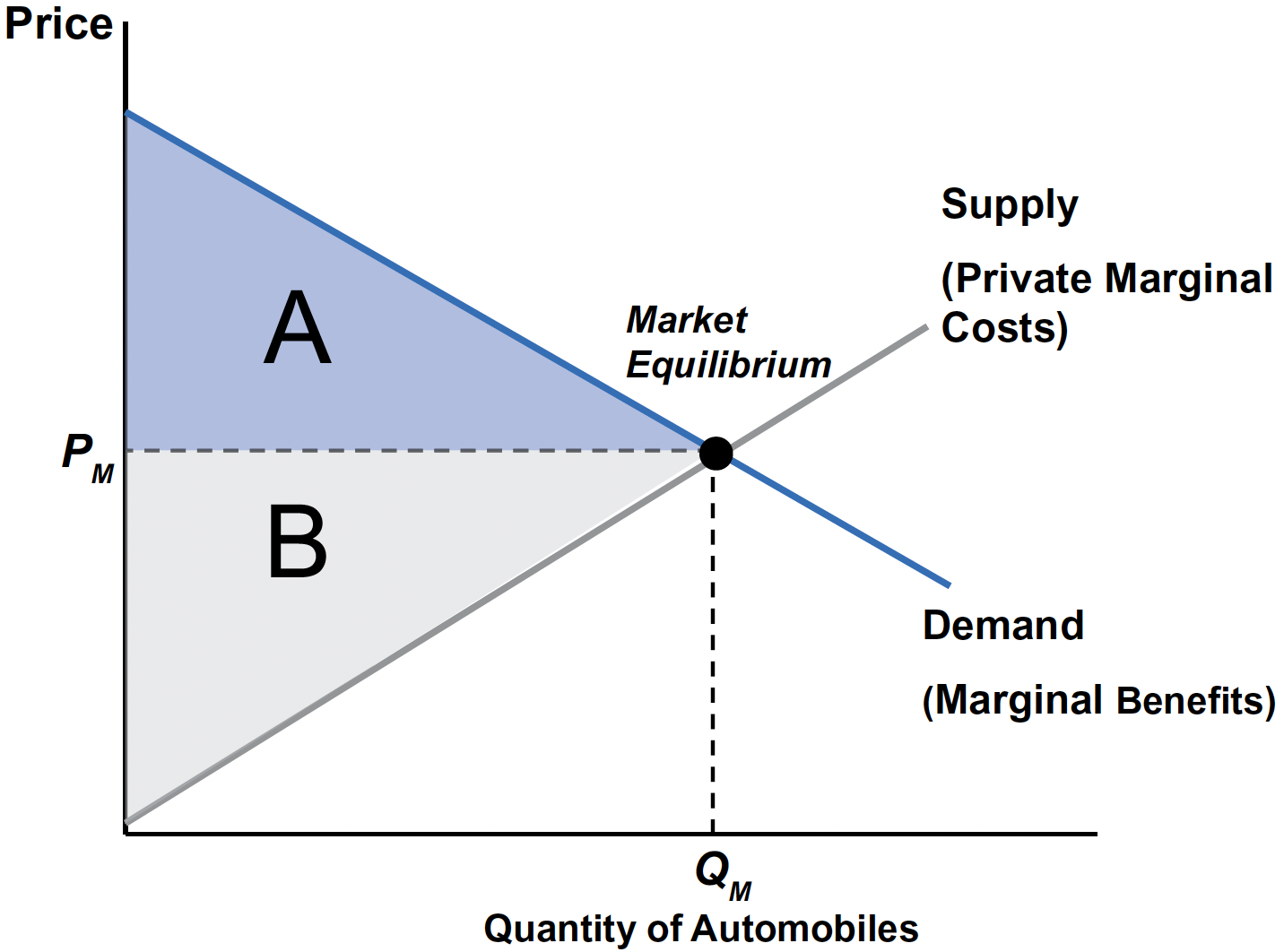

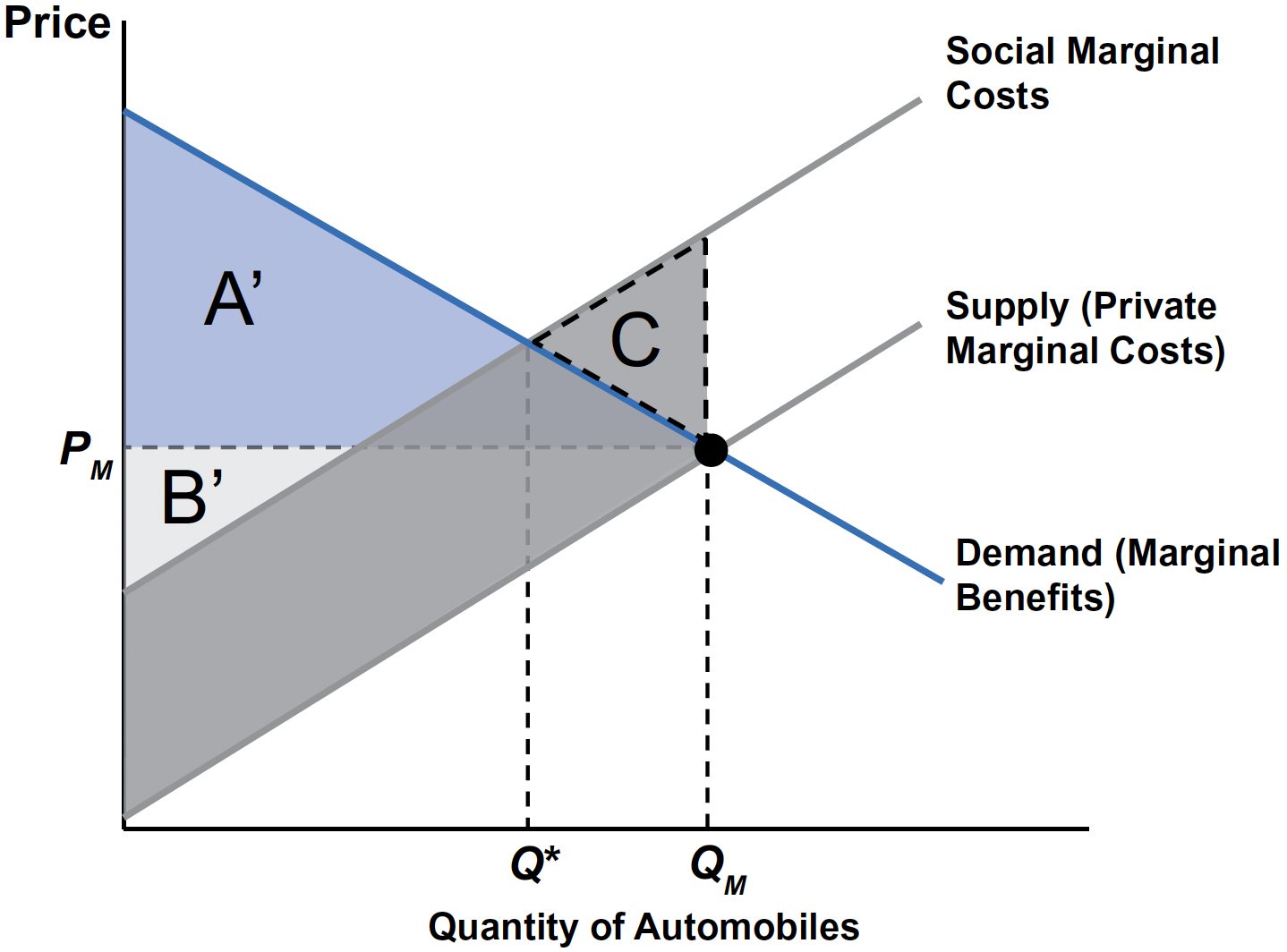

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

- Consumer Surplus (CS): Area under demand and above price.

- Producer Surplus (PS): Area above supply (PMC) and below price.

- Without externalities, equilibrium maximizes CS + PS.

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

Without Pigouvian Tax

Without Pigouvian tax, consumers and producers enjoys higher CS and PS than with the tax.

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

Without Pigouvian Tax

However, these market activities impose a negative external costs to third parties, represented by the area between PMC and SMC up to the chosen quantity (\(Q_{M}\)).

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

Without Pigouvian Tax

With such a negative externality, true social welfare (SW) is: \[ \begin{align} &\quad\;\; (\text{SW})\,=\, (\text{CS} + \text{PS}) \,-\, (\text{External Cost}). \end{align} \]

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

Without Pigouvian Tax

Triangle C is the deadweight loss from overproduction where SMC > MB.

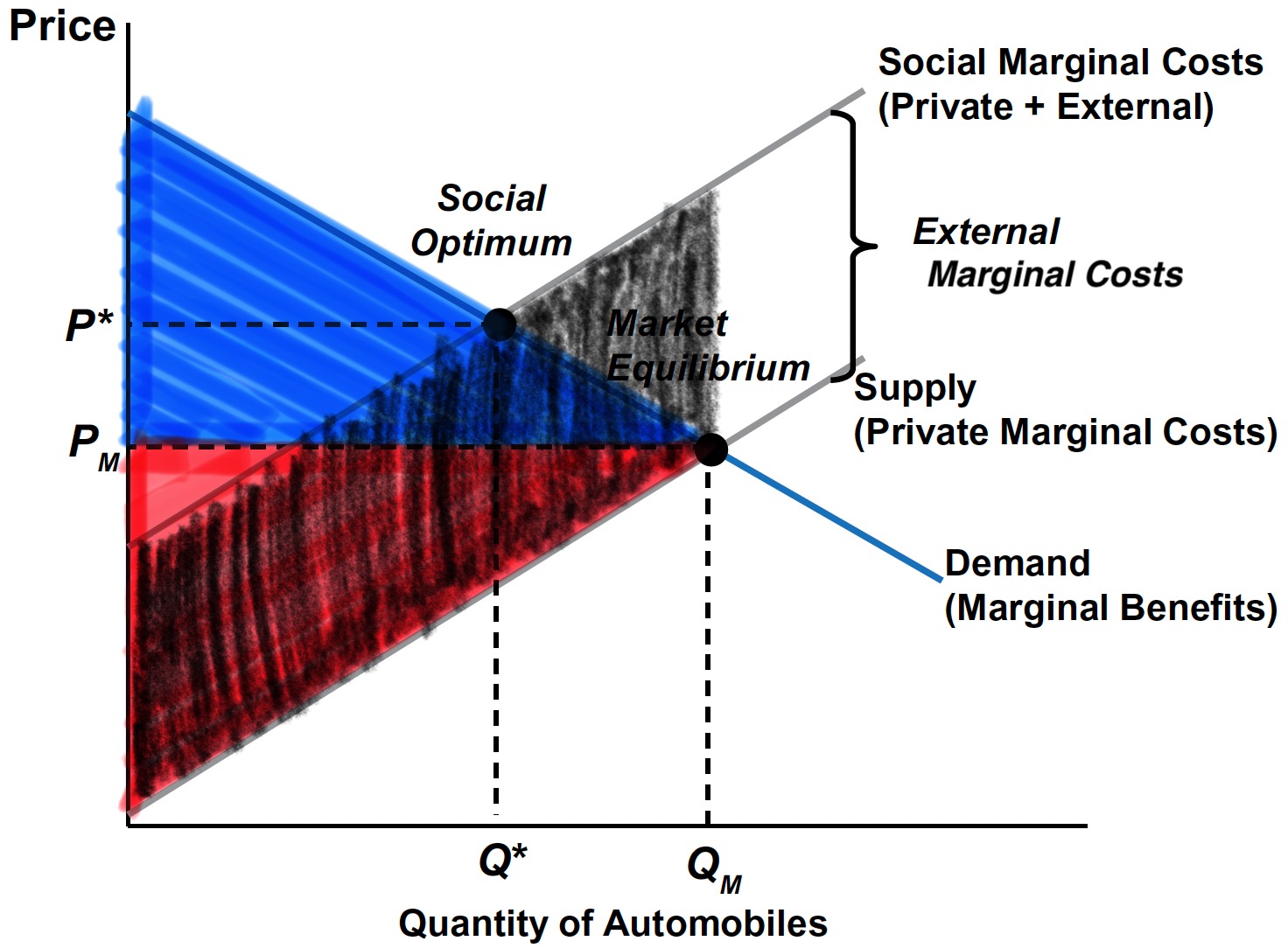

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

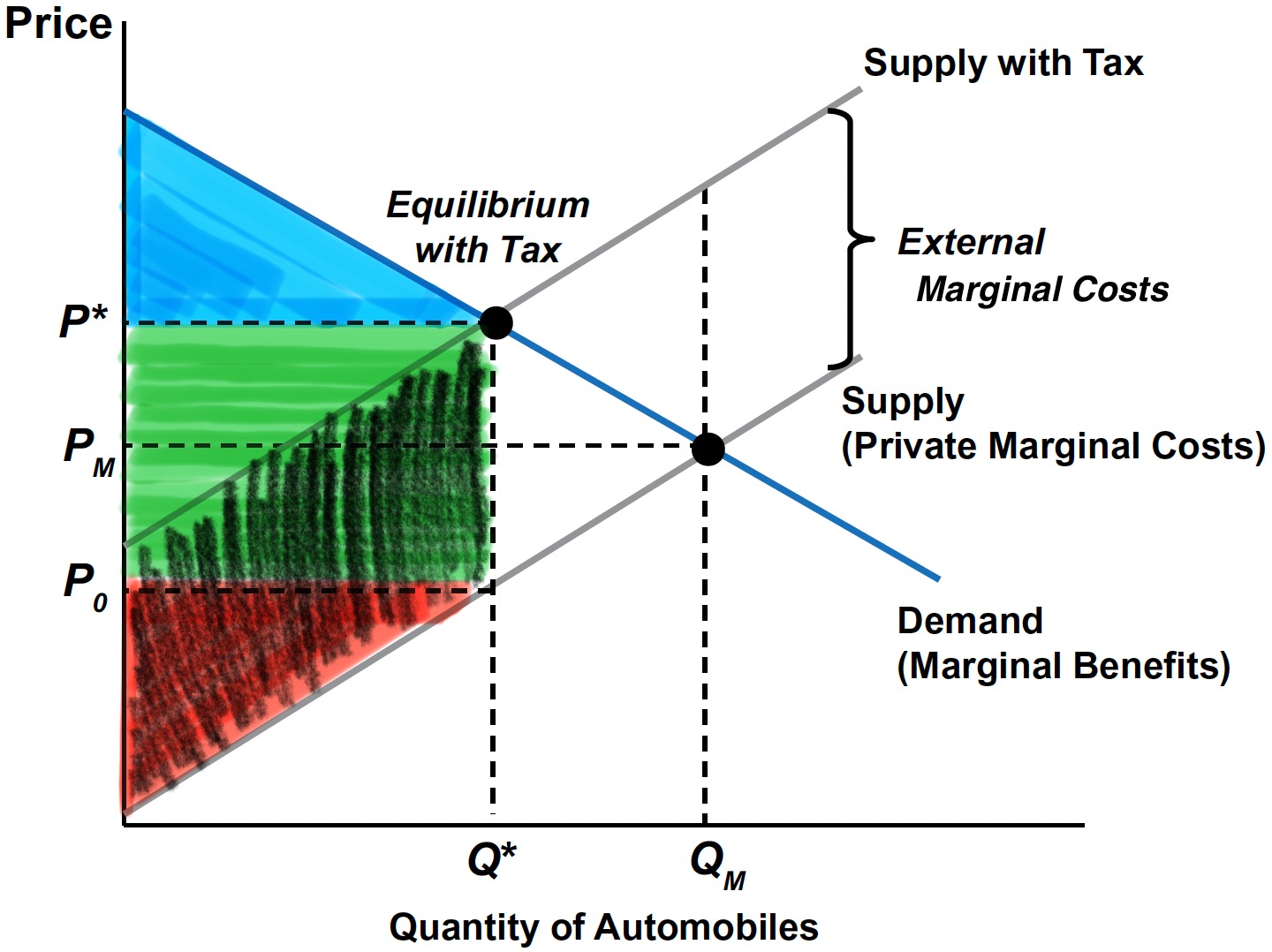

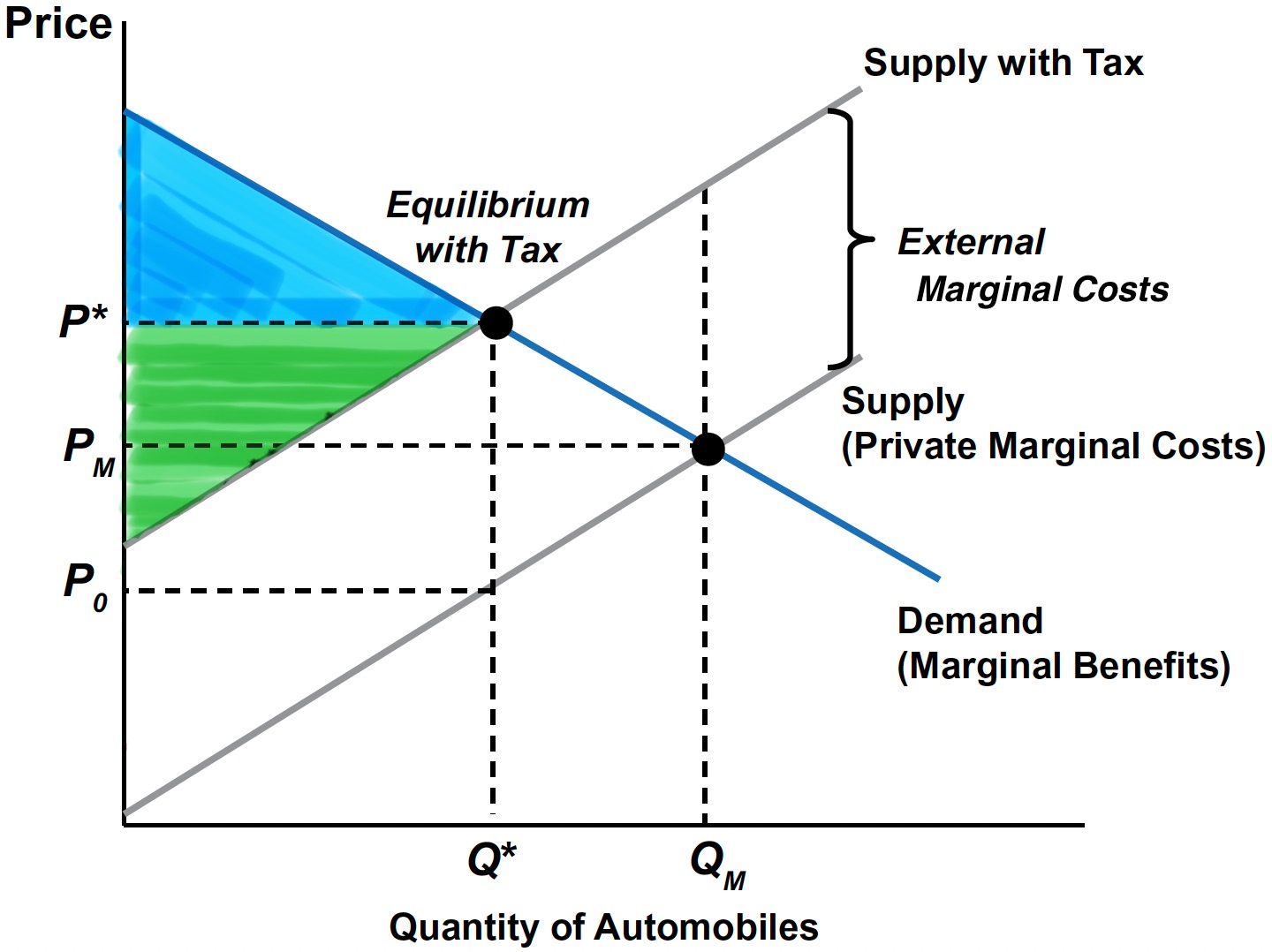

With Pigouvian Tax

With Pigouvian tax, CS and PS are measured over quantities from 0 to \(Q^{*}\), the new equilibrium quantity.

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

With Pigouvian Tax

Tax revenue equals \(t\times Q^{*}\).

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

With Pigouvian Tax

Pigouvian tax caps external damage by shifting the market to the efficient quantity \(Q^{*}\).

Welfare Analysis of the Automobile Market

With Pigouvian Tax

With such a negative externality, true social welfare (SW) is: \[ \begin{align} &\quad\;\; (\text{SW})\,=\, (\text{CS} + \text{PS} + \text{Tax Revenue}) \,-\, (\text{External Cost}). \end{align} \]

- Pigovian Tax Improves Welfare: welfare rises by C relative to the unregulated outcome.

Optimal Pollution

- Zero pollution generally implies zero production; instead, economists seek the efficient (not necessarily zero) level of pollution given current technology and preferences.

- The Pigovian tax yields optimal (residual) pollution—the remaining damages at \(Q^{*}\).

- Caveat: If demand shifts right (e.g., autos more valued), the efficient pollution level can rise—raising questions about science‑based caps vs. pure efficiency.

Note

- Preferences (what people want—demand) and technology (what/how much outputs can be produced from scarce inputs—supply), given endowments (initial resources) and prices, jointly determine market equilibrium and welfare, as consumers maximize utility and firms maximize profit.

- Policy practice often sets health‑based standards (e.g., the Clean Air Act) and then uses market instruments to achieve those standards cost‑effectively.

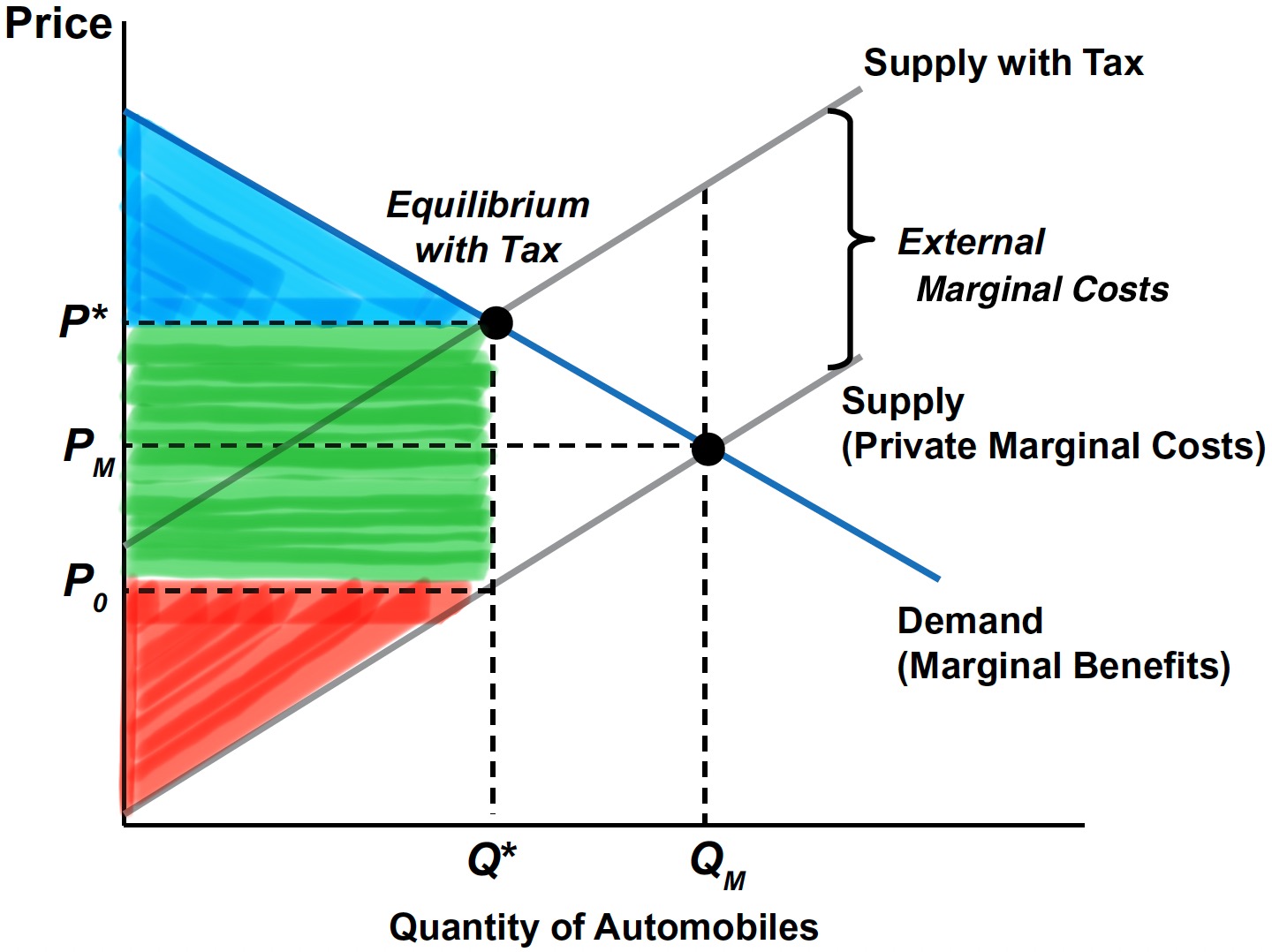

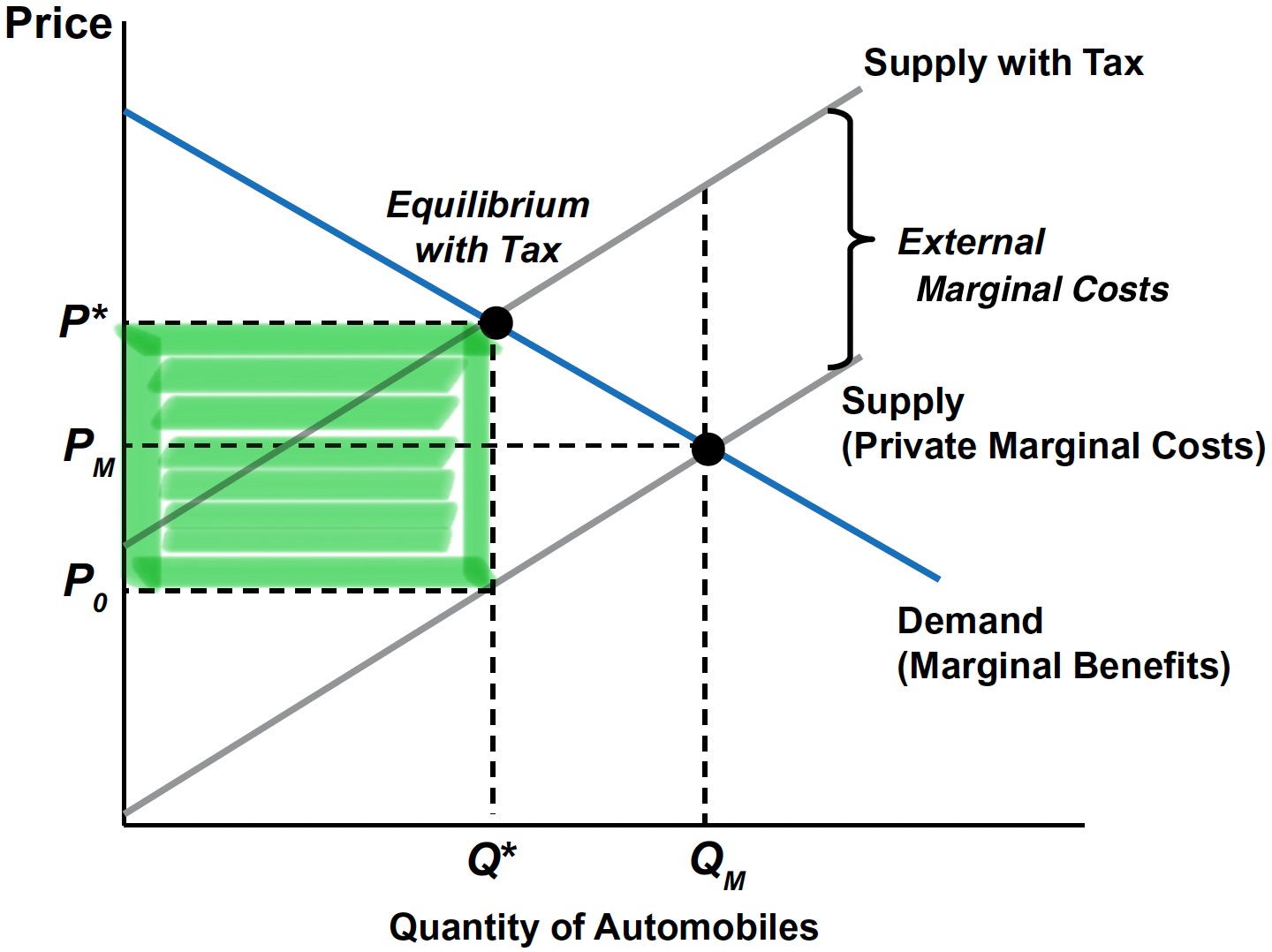

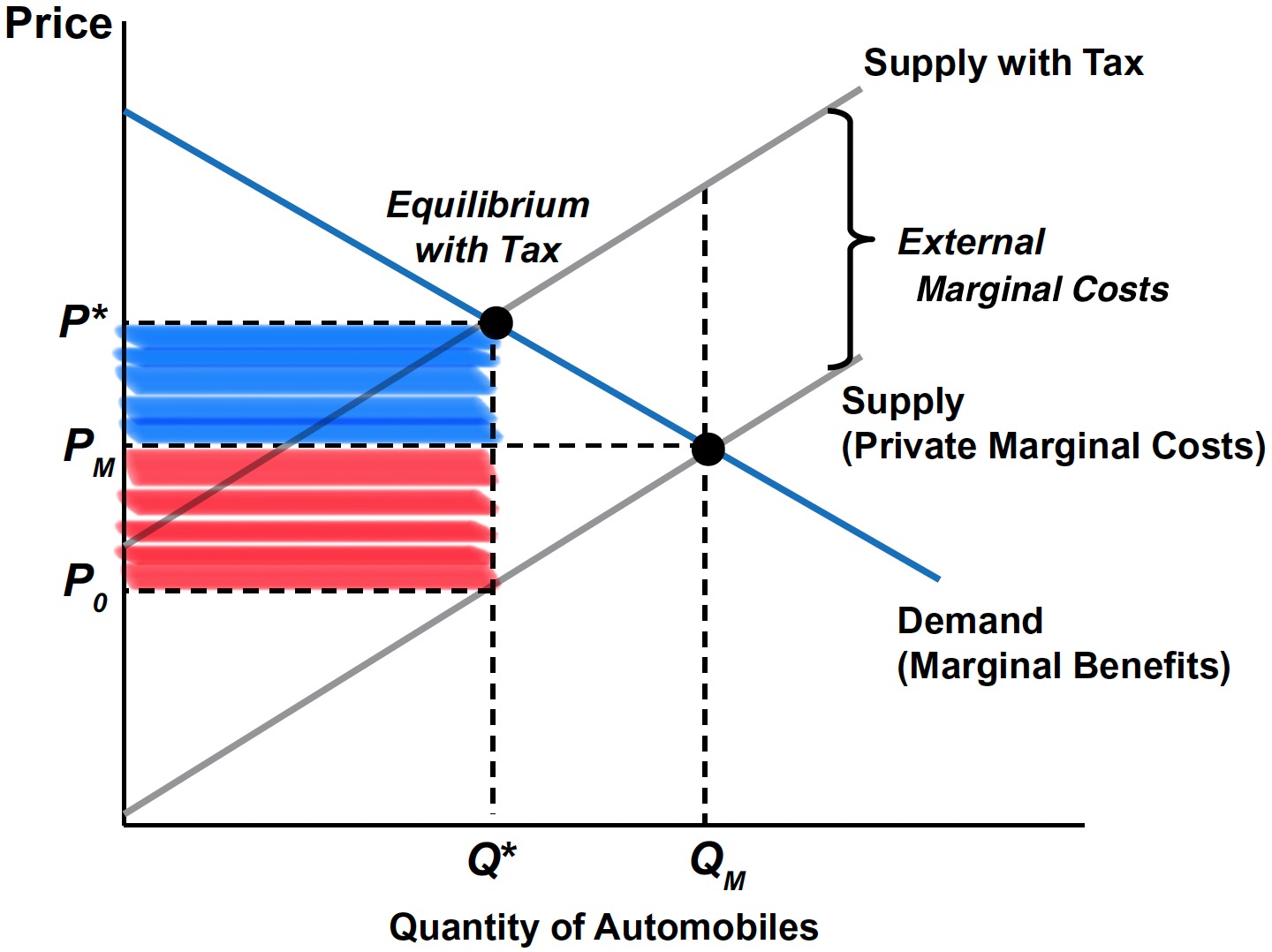

Tax Incidence

Tax Revenue: \(t \times Q^{*}\)

Tax incidence: The division of the tax burden between consumers and producers, determined by the relative elasticities of demand and supply.

Tax Incidence

Consumer incidence: The amount to which CS decreases, measured over quantities from \(0\) to \(Q^{*}\) \(\;\rightarrow\;\) Tax falls on consumers, who pay \(P^{*} - P_{M}\) more per unit.

Producer incidence: The amount to which PS decreases, measured over quantities from \(0\) to \(Q^{*}\) \(\;\rightarrow\;\) Tax falls on producers, who receive \(P_{M} - P_{0}\) less per unit.

Tax Incidence: Ordinary vs. Pigouvian Tax

Ordinary Tax (in a Competitive Market)

- Incidence:

- Consumers pay higher price (\(P^{*} - P_{M}\)).

- Producers receive lower price (\(P_{M} - P_{0}\)).

- Consumers pay higher price (\(P^{*} - P_{M}\)).

- Welfare effect:

- Creates deadweight loss (DWL).

- Total surplus falls.

- Creates deadweight loss (DWL).

Pigouvian Tax

- Incidence:

- Consumers and Producers still share burden depending on elasticities.

- Consumers and Producers still share burden depending on elasticities.

- Welfare effect:

- Internalizes externality (e.g., pollution).

- Reduces overproduction: \(Q_{M} \rightarrow Q^{*}\).

- Improves social welfare by offsetting external damages.

- Internalizes externality (e.g., pollution).