Lecture 5

Property Rights, the Coase Theorem, and the Environment

September 15, 2025

Property Rights, the Coase Theorem, and the Environment

Pigovian Taxes and Rights

- A Pigovian tax makes polluters pay for the external damages they impose on society.

- Implicit assumption:

- Society has a right to clean environment and to be compensated for damages.

- Polluters do not have unlimited rights to emit.

- Society has a right to clean environment and to be compensated for damages.

- Intuitively appealing, but raises a broader question:

- Who owns the right in cases of environmental harm?

- The polluter, or society at large?

- Who owns the right in cases of environmental harm?

A Wetland Example: Competing Rights

- Farmer Alpha drains a wetland to grow crops → earns $5,000 profit.

- Downstream neighbor Beta loses $8,000 in crop damage from flooding.

- Question:

- Does Alpha’s property ownership give him the right to drain?

- Or does Beta (or society) have the right to protection from harm?

- Does Alpha’s property ownership give him the right to drain?

Negotiation with Alpha Holding Rights

- Suppose Alpha has the legal right to drain.

- Beta can offer to pay him to keep the wetland intact.

- Beta’s willingness to pay: up to $8,000 (her avoided damages).

- Alpha’s willingness to accept: at least $5,000 (his foregone profit).

- This creates a bargaining range: $5,000–$8,000.

- Beta can offer to pay him to keep the wetland intact.

- Example outcome: Beta pays Alpha $6,000.

- Alpha gains $1,000 more than draining.

- Beta avoids $8,000 damage, but still pays $6,000 → net $2,000 better off.

- The actual payment depends on each side’s bargaining power.

- Alpha gains $1,000 more than draining.

- Efficient result: wetland preserved.

Negotiation with Alpha Holding Rights

Why Beta Could Still Be “Unhappy”

- Beta is better off than if Alpha drained ($2,000 net gain).

- But she could still feels burdened because:

- She pays a large sum to prevent harm.

- She may believe she should not have to pay at all.

- She pays a large sum to prevent harm.

- Lesson: Efficiency ≠ Equity.

- Efficient outcomes can still feel unfair.

Negotiation with Beta Holding Rights

- Suppose the law gives Beta the right to a wetland.

- Alpha must buy permission to drain.

- With current values:

- Alpha can offer up to $5,000 (his potential profit).

- Beta demands at least $8,000 (her avoided loss).

- Alpha can offer up to $5,000 (his potential profit).

- No agreement possible → wetland preserved (same efficient outcome)

- Alpha must buy permission to drain.

- Outcome is identical regardless of who holds the rights—Wetland stays intact.

Negotiation with Beta Holding Rights

A Change in Payoffs

- Imagine a new crop grows well on drained wetlands.

- Alpha’s profit rises to $12,000.

- Beta still faces $8,000 in damages.

- Alpha’s profit rises to $12,000.

- Now negotiation is possible:

- Alpha can pay Beta between $8,000 and $12,000.

- Example: $10,000 payment →

- Alpha nets $2,000.

- Beta nets $2,000.

- Alpha nets $2,000.

- Alpha can pay Beta between $8,000 and $12,000.

- Takeaway: Efficient outcome depends on relative benefits and costs, not on initial assignment of rights.

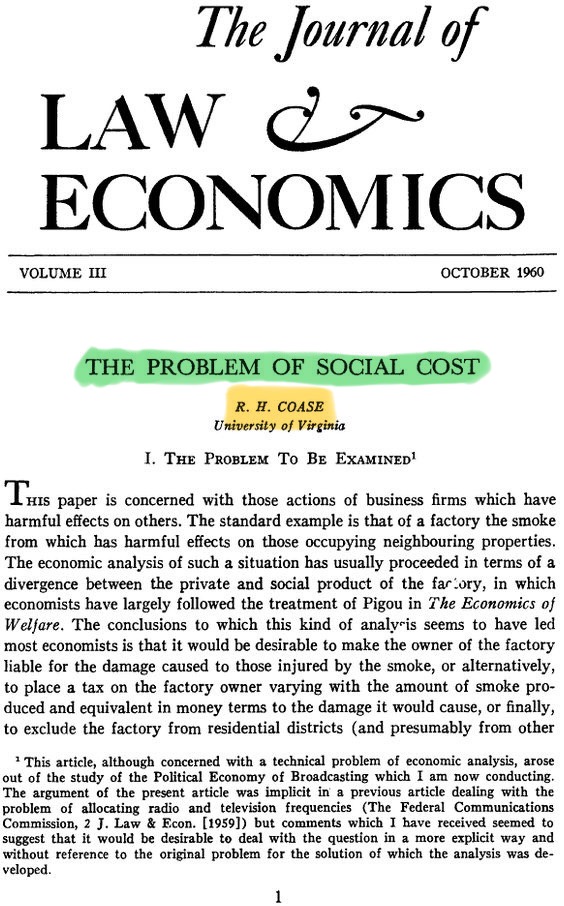

The Coase Theorem

- Transaction costs: Expenses of making a deal or negotiation (e.g., legal fees, administrative costs, or costs of bringing parties together).

- The Coase Theorem:

- If property rights are well defined and transaction costs are negligible,

- Then private bargaining will lead to efficient allocation of resources,

- Even when externalities are present.

- If property rights are well defined and transaction costs are negligible,

- Rights determine who pays whom, but not the final efficient outcome.

- Assumes: Perfect information; Few parties; No high legal or enforcement costs.

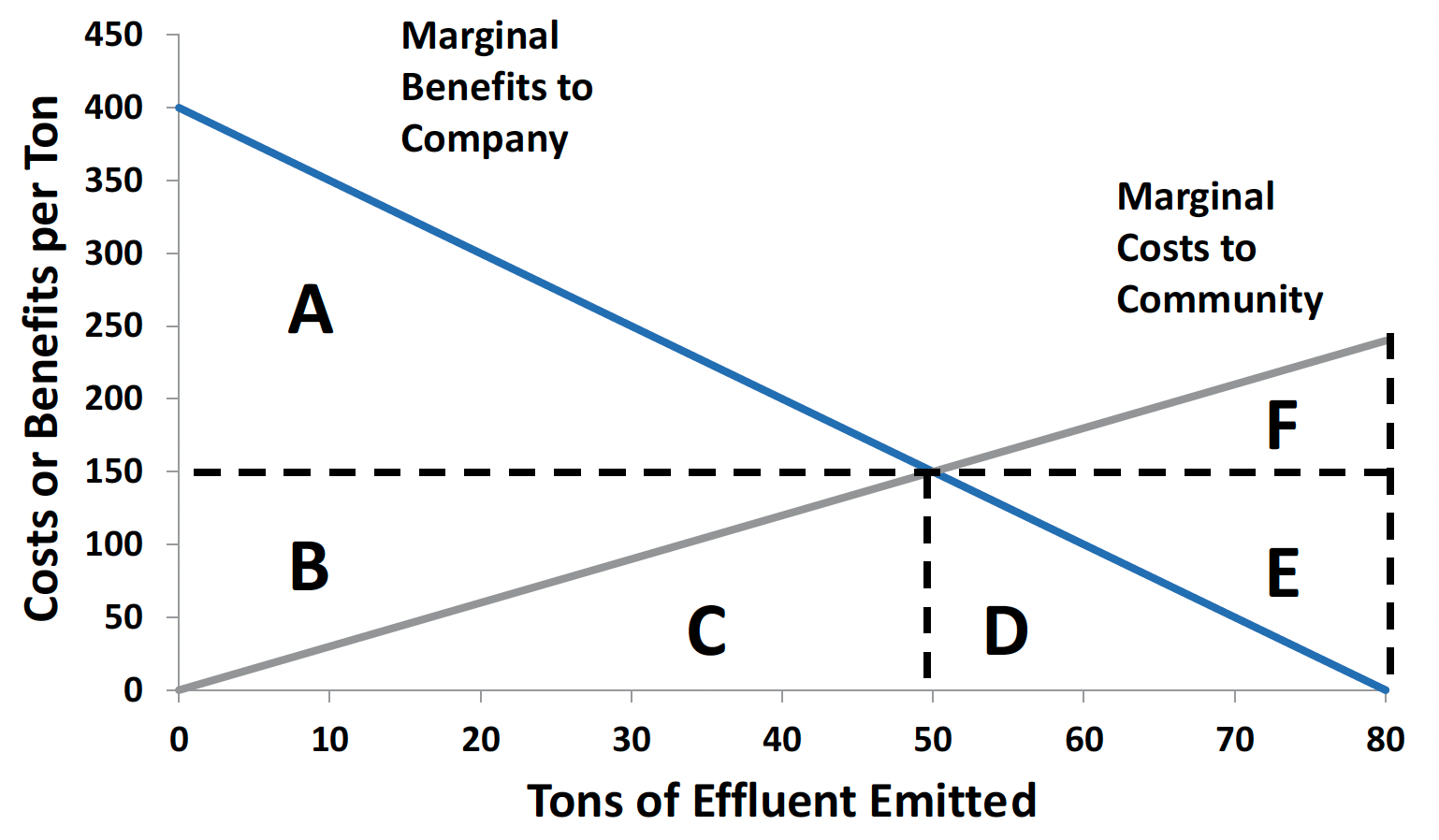

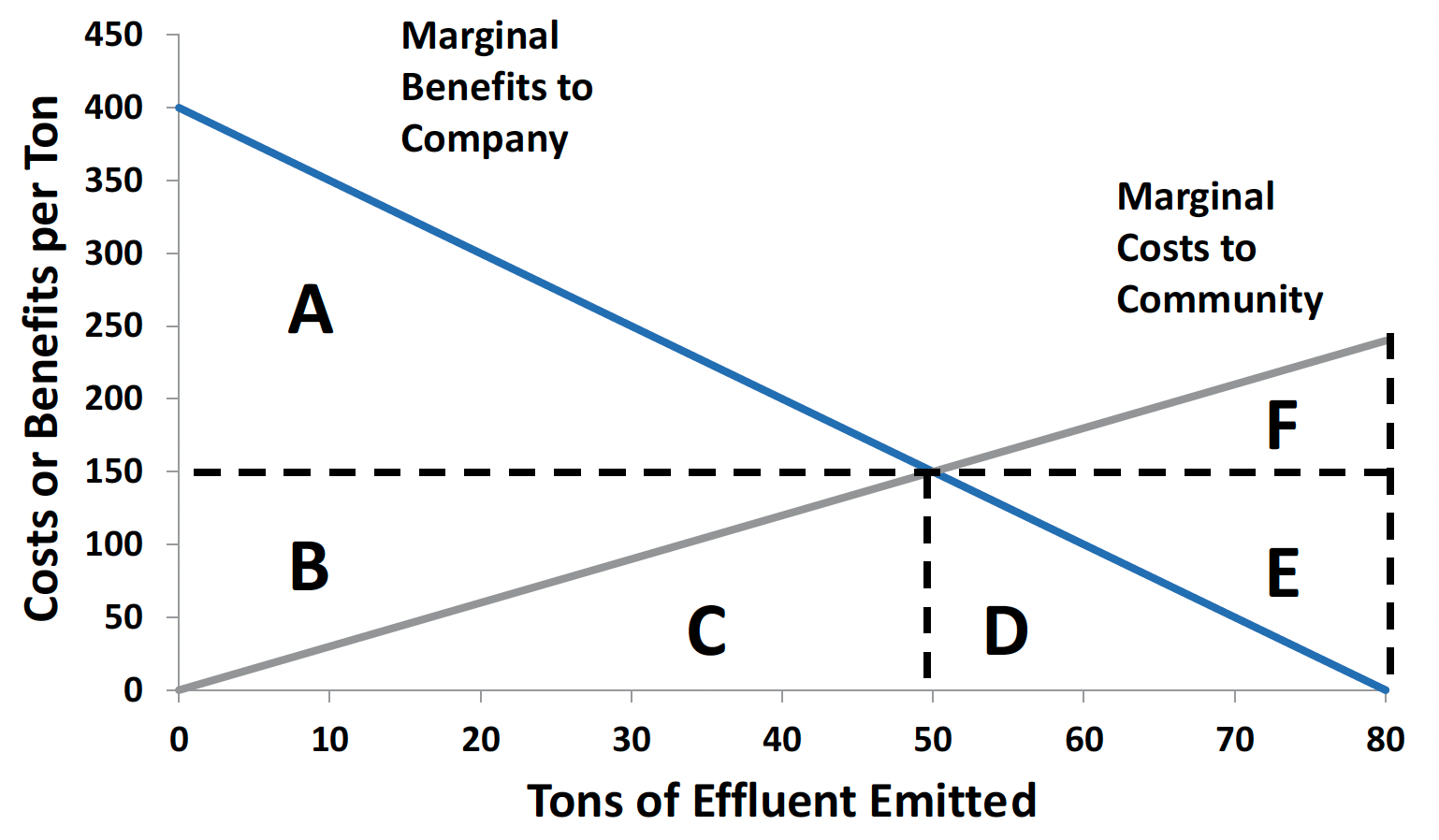

Welfare Analysis of Company vs. Community

- Company emits 80 tons of effluent into a river.

- Company gains profits (MB of pollution).

- Community bears damages (MC of pollution).

- Company gains profits (MB of pollution).

- Efficient solution: 50 tons, where MB = MC.

- Beyond 50, extra damage > extra profit.

- Below 50, extra profit > extra damage.

- Beyond 50, extra damage > extra profit.

Negotiation with Community Holding Rights

- Assume:

- Pollution rights sell for $150 each.

- The community owns the rights.

- Pollution rights sell for $150 each.

- At 50 tons: MB = MC = $150.

- Company’s payments = $7,500 (area B + C).

- Company benefits = $13,750 (area A + B + C).

- Total community damages = $3,750 (area C).

- Company’s payments = $7,500 (area B + C).

- Net results:

- Company’ Net Benefit: $6,250.

- Community’s Net Benefit: $3,750.

- Social Welfare = $10,000.

- Company’ Net Benefit: $6,250.

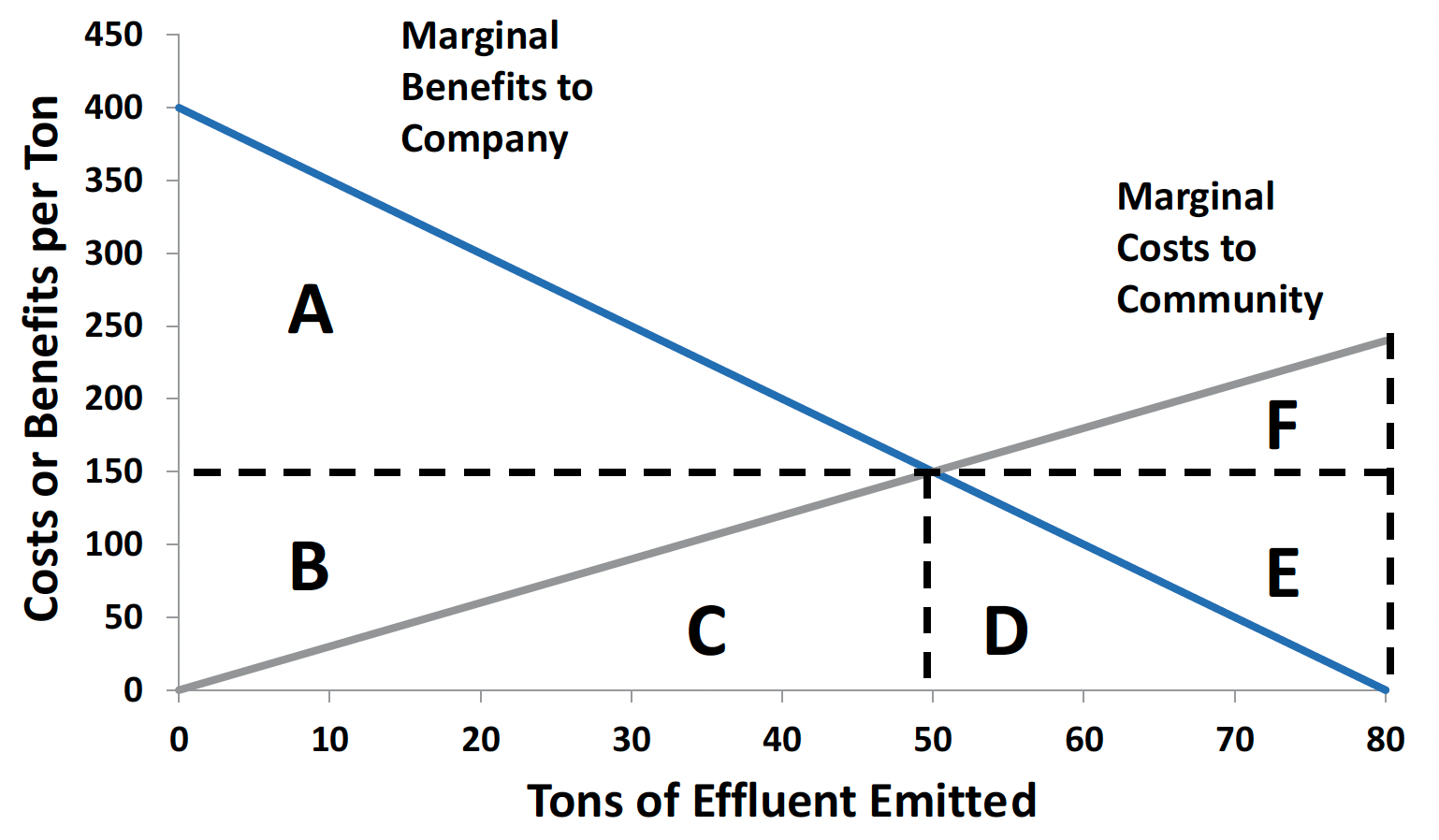

Negotiation with Company Holding Rights

- Assume:

- Pollution rights sell for $150 each.

- The company owns the rights.

- Pollution rights sell for $150 each.

- At 50 tons: MB = MC = $150.

- Community’s payments = $4,500 (area D + E).

- Company benefits = $13,750 (area A + B + C).

- Total community damages = $3,750 (area C).

- Community’s payments = $4,500 (area D + E).

- Net results:

- Company’s Net Benefit: $18,250.

- Community’ Net Benefit:

-$8,250.

- Social Welfare = $10,000.

- Company’s Net Benefit: $18,250.

- Distribution of welfare differs.

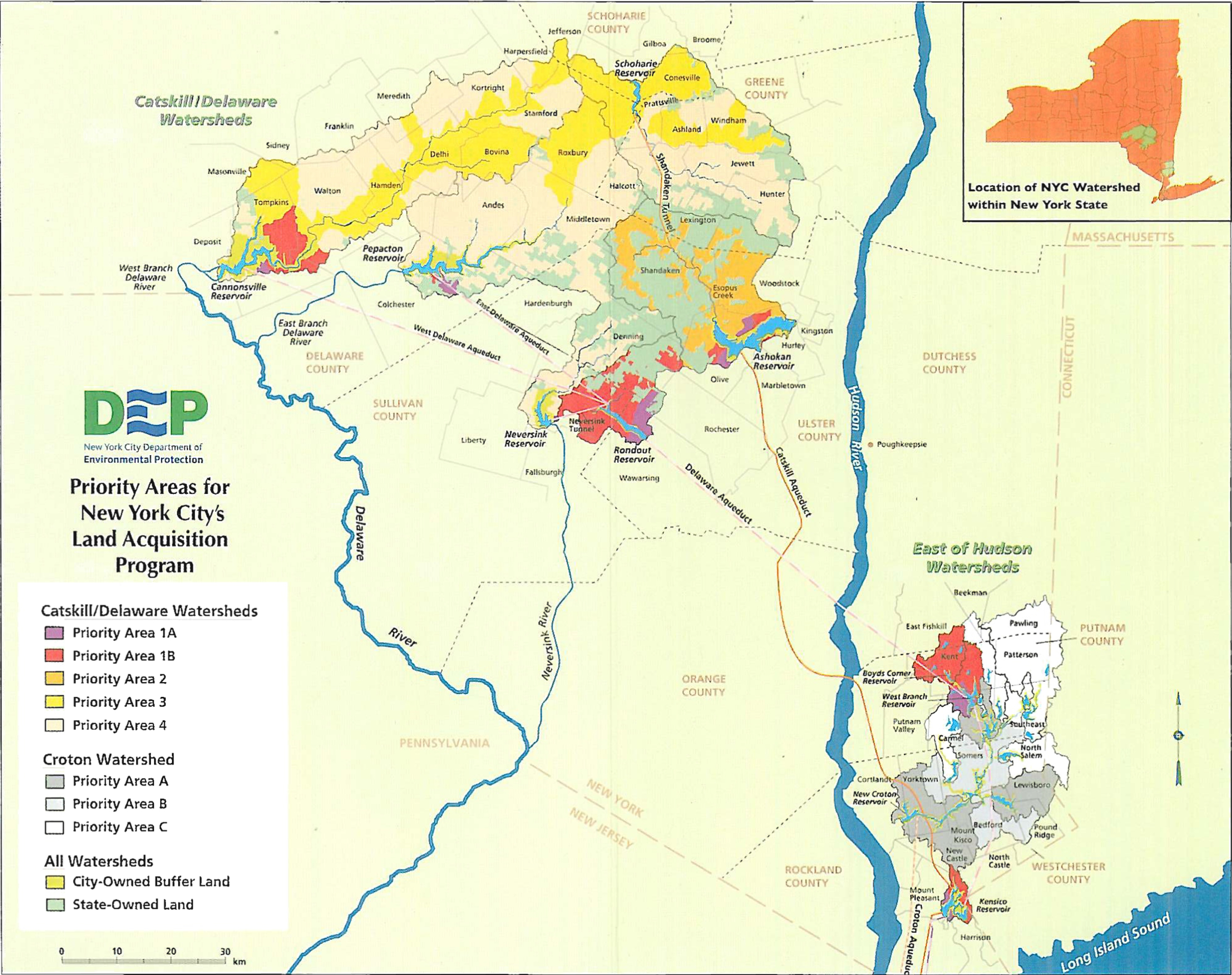

Case Study: NYC Land Acquisition Program

- NYC must provide clean drinking water for 8.4 million people.

- Option 1: Build massive water filtration plants (very costly).

- Option 2: Protect watersheds upstream by buying land & easements.

- Option 1: Build massive water filtration plants (very costly).

- NYC purchased property rights voluntarily (no eminent domain used):

- Acquire 355,000+ acres from willing sellers; Pay fair market value.

- Acquire 355,000+ acres from willing sellers; Pay fair market value.

- Cheaper than filtration; Clean water maintained; Example of Coasean bargaining on a large scale.

Property Rights and Takings

- Eminent Domain: Gov’t may take land for public use but must pay compensation (Fifth Amendment).

- Taking: Any gov’t action that deprives an owner of property rights.

- Regulatory Takings: Laws that restrict land use and may reduce property value.

- Regulatory Takings: Laws that restrict land use and may reduce property value.

- Supreme Court Ruling – Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council:

- South Carolina Law barred building on Lucas’s beachfront lots.

- Ruling: A regulation that removes all economic use of land is a taking → compensation required.

- South Carolina Law barred building on Lucas’s beachfront lots.

| Type of Taking | Definition | Compensation? | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Taking | All economic use eliminated | ✅ Yes | Rare |

| Partial Taking | Some economic use remains | ❌ No | Common |

- Q: What is the rationale for not requiring compensation in cases of partial takings?

Limits of the Coase Theorem

- The Promise of Coase

- In theory, if property rights are clearly assigned, parties can negotiate efficient outcomes without government intervention.

- This idea underpins free market environmentalism—the belief that expanding property rights and market mechanisms can handle pollution control.

- In theory, if property rights are clearly assigned, parties can negotiate efficient outcomes without government intervention.

- The Reality: Transaction Costs

- Efficient bargaining assumes low transaction costs, but in practice these costs can be very high.

- When only two parties negotiate (e.g., Alpha and Beta), costs are manageable.

- With 50 downstream communities and multiple factories, negotiation becomes cumbersome, maybe impossible.

- Efficient bargaining assumes low transaction costs, but in practice these costs can be very high.

Limits of the Coase Theorem

- Free-Rider Effect

- Some communities may wait for others to pay off the polluter, hoping to enjoy benefits without contributing.

- This leads to undersupply of pollution reduction.

- Example: if one community refuses to contribute, others may hesitate too, and no deal is reached.

- Some communities may wait for others to pay off the polluter, hoping to enjoy benefits without contributing.

- Holdout Effect

- When many parties must agree, a single holdout can block progress by demanding more compensation.

- Example: 49 communities agree, but the 50th demands excessive payment, threatening to veto the entire agreement.

- Like free-riding, this prevents efficient negotiation.

- When many parties must agree, a single holdout can block progress by demanding more compensation.

Limits of the Coase Theorem

- Nonhuman and Ecosystem Impacts

- Many environmental damages harm ecosystems, plants, or animals rather than identifiable individuals.

- Who bargains for the survival of birds, bees, or endangered species?

- Groups like The Nature Conservancy buy land to preserve ecosystems, but their reach is limited.

- In markets, ecological values often lose to economic ones.

- Many environmental damages harm ecosystems, plants, or animals rather than identifiable individuals.

- Future Generations

- Property rights usually apply to the current generation.

- Climate change, fisheries depletion, and species extinction impose costs on future people with no voice in today’s negotiations.

- Markets alone cannot ensure intergenerational fairness.

- Property rights usually apply to the current generation.

Limits of the Coase Theorem - Equity Concerns

- Poor communities may lack the resources to “buy out” polluters, even when health damages are severe.

- They might accept hazardous facilities out of desperation for compensation.

- Meanwhile, wealthier communities can afford to preserve open space, while poorer ones cannot.

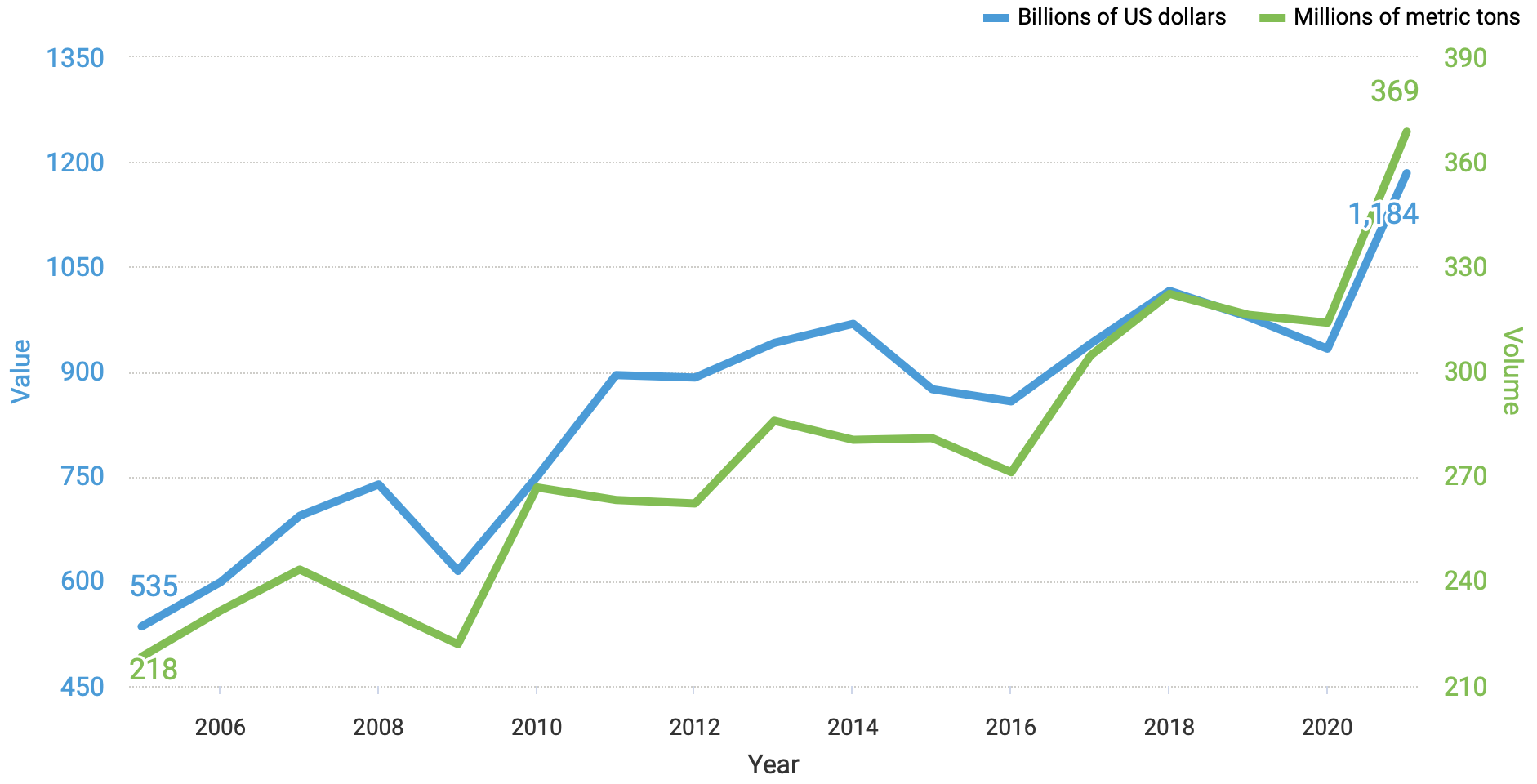

- Example: Global plastic waste trade

- High-income countries export waste to poorer nations that accept environmental risks for financial gain.

- A large share of traded plastics is mismanaged.

- For decades, China was the largest importer, receiving 72% of global plastic waste exports and mismanaging about 76% of it (EIA, 2021).

- High-income countries export waste to poorer nations that accept environmental risks for financial gain.

Global plastics trade hits record $1.2 trillion

Global plastics trade hits record $1.2 trillion

Environmental Justice

- Defined by EPA: “Fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income.”

- Example: Flint, Michigan Water Crisis (2014–)

- City switched to Flint River water, which was corrosive and not treated properly → lead contamination.

- 6,000–12,000 children exposed.

- Community largely low-income and African-American.

- City switched to Flint River water, which was corrosive and not treated properly → lead contamination.

- Lesson: Markets alone cannot ensure fairness in environmental outcomes.

Environmental Justice

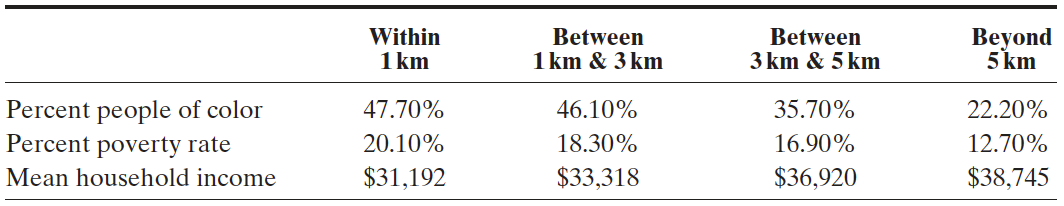

Race, Poverty and Hazardous Waste Facilities

Do polluting industries choose to locate in poor and minority communities—where land is cheaper and political resistance is weaker?

Or do low-income households move in near toxic storage or disposal facility (TSDF) after they are built, attracted by lower housing costs?

Pastor et al. (2016), “Which Came First? Toxic Facilities, Minority Move-In, and Environmental Justice”:

- A 10% point increase in minority population share was linked to ~34–39% higher odds of a TSDF siting.

- The pace of increase in minority residents near TSDFs was similar to the pace elsewhere in the region.