Lecture 6

Common Property and Open Access Regimes

September 26, 2025

Common Property, Open Access, and Property Rights

Four Property-Right Regimes: The Landscape

- Private property is not the only way to define entitlements to resource use. Consider:

- State-property regimes — government owns and controls access and rules.

- Common-property regimes — a specified group co-owns and co-manages the resource.

- Res nullius / Open access regimes — no owner, no authority to exclude or set rules.

- Each regime creates distinct incentives for harvest, investment, monitoring, and conservation.

State Property — Design & Pitfalls

- Present to some degree in virtually all countries (e.g., parks, wilderness preserves).

- Upside: Can pursue social objectives (biodiversity, equity) with legal authority to exclude/enforce.

- Risk: Principal–agent problems—bureaucratic incentives may diverge from society’s interests (e.g., budget maximization, political influence, information gaps).

- Principal–agent problems: the conflict that arises when one party (the principal) delegates authority to another party (the agent) to act on their behalf, and the agent’s interests do not align with the principal’s.

- Performance hinges on: credible science, monitoring/enforcement capacity, accountability.

Common Property — When It Works (and When It Doesn’t)

- Definition: Shared resources managed in common by a defined group; rights may be formal (law) or informal (custom).

- Efficiency & sustainability depend on rule quality (fit to ecology), compliance, conflict resolution, and trust.

- Reality check: Many successes exist—but breakdowns are common when cohesion or enforcement erodes.

Common Property — When It Works (and When It Doesn’t)

Case: Swiss Alpine Meadows (Common Property Success)

- Grazing treated as common property for centuries.

- User associations set stocking rules; stable membership fostered reciprocity and trust.

- Outcome: Overgrazing discouraged; compliance high; sustained yields.

Case: Mawelle, Sri Lanka (Governance Breakdown)

- Initially: Rotating rights over fishing spots/times ensured equity and protected stocks.

- Later: Population growth + outsiders eroded cohesion; rules became unenforceable.

- Outcome: Overexploitation and lower incomes.

- Success ingredients: reciprocity, stable membership, transparent rules, graduated sanctions, local monitoring.

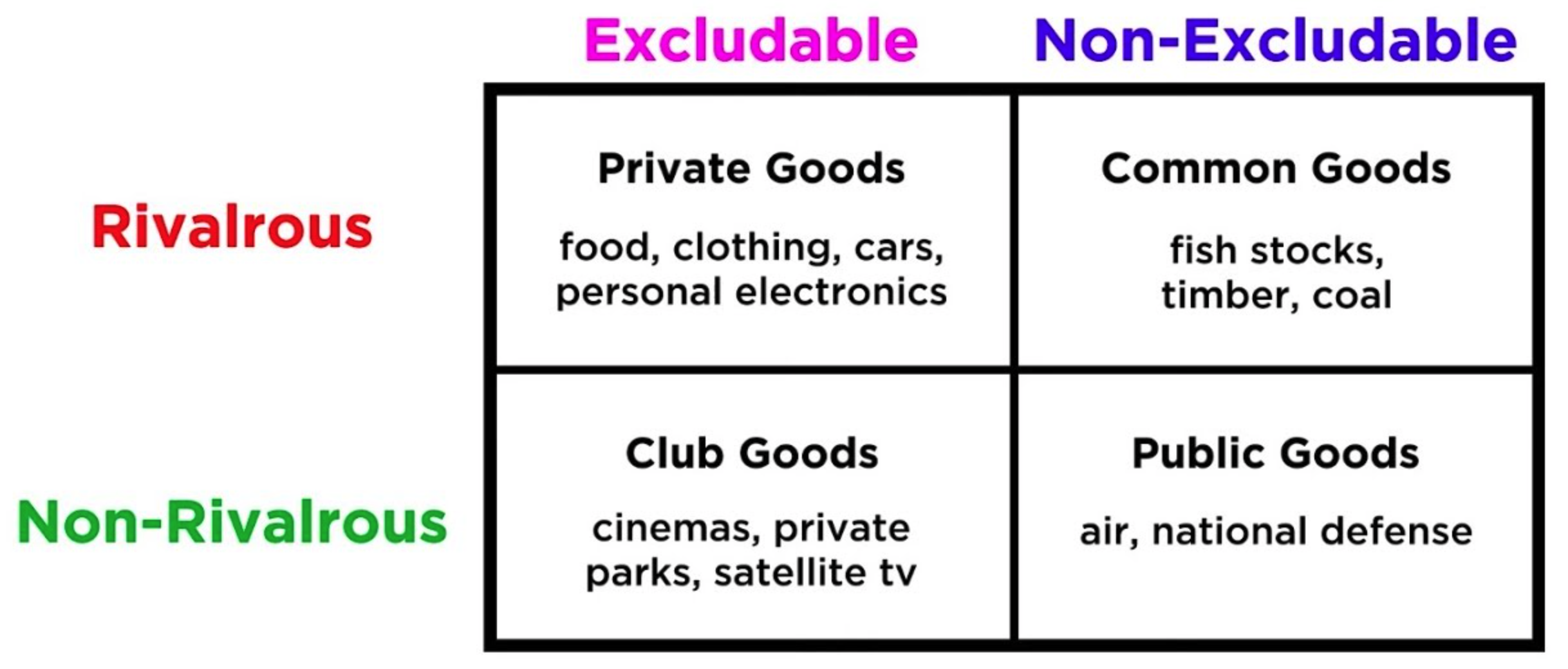

Rivalry & Excludability

Rival? Does one user’s harvest reduce what’s left for others?

Excludable? Can users who haven’t paid be kept out?

Open Access (Res nullius) — The Core Problem

- No one can exclude ⇒ access is nonexcludable; the stock is rival (one user’s harvest reduces others’).

- Result: First-come, first-served use; individuals ignore the stock externality on others and the future.

- Popular label: “Tragedy of the open-access commons”—overuse and dissipation of economic rents as scarcity grows.

Note

- Economic rent is the extra return to a resource (like land, fish, or oil) above the minimum payment necessary to keep it in use.

Incentives by Regime

| Attribute | Private | State | Common | Open Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excludability | High | High (by law) | Group-limited | None |

| Who sets rules? | Owner(s) | Government | Co-owners | No one |

| Who captures rents? | Owner(s) | Public (in principle) | Co-owners | No one (dissipated) |

| Typical risks | Externalities; market power | Principal–agent problem; info gaps | Cohesion/monitoring failures | Overuse; collapse risk |

Note

Key distinction: Open access ⟂ Common property.

Open access = common property without effective rules or governance.

All open-access resources are common-pool resources (CPR), but not all common-pool resources are open access.

- Rights → incentives → outcomes.

- Durable solutions rely on clear rights, credible rules, and effective enforcement—via private, state, or common governance, often in hybrid forms.

American Bison as a Common-Pool Example

- Early U.S. period:

- Abundant bison; unrestricted hunting did not impose noticeable scarcity costs.

- As demand/technology rose:

- Scarcity emerged; each hunter’s effort reduced others’ catch per unit effort.

- Open access + scarcity ⇒ escalating effort, falling stocks, near-extinction.

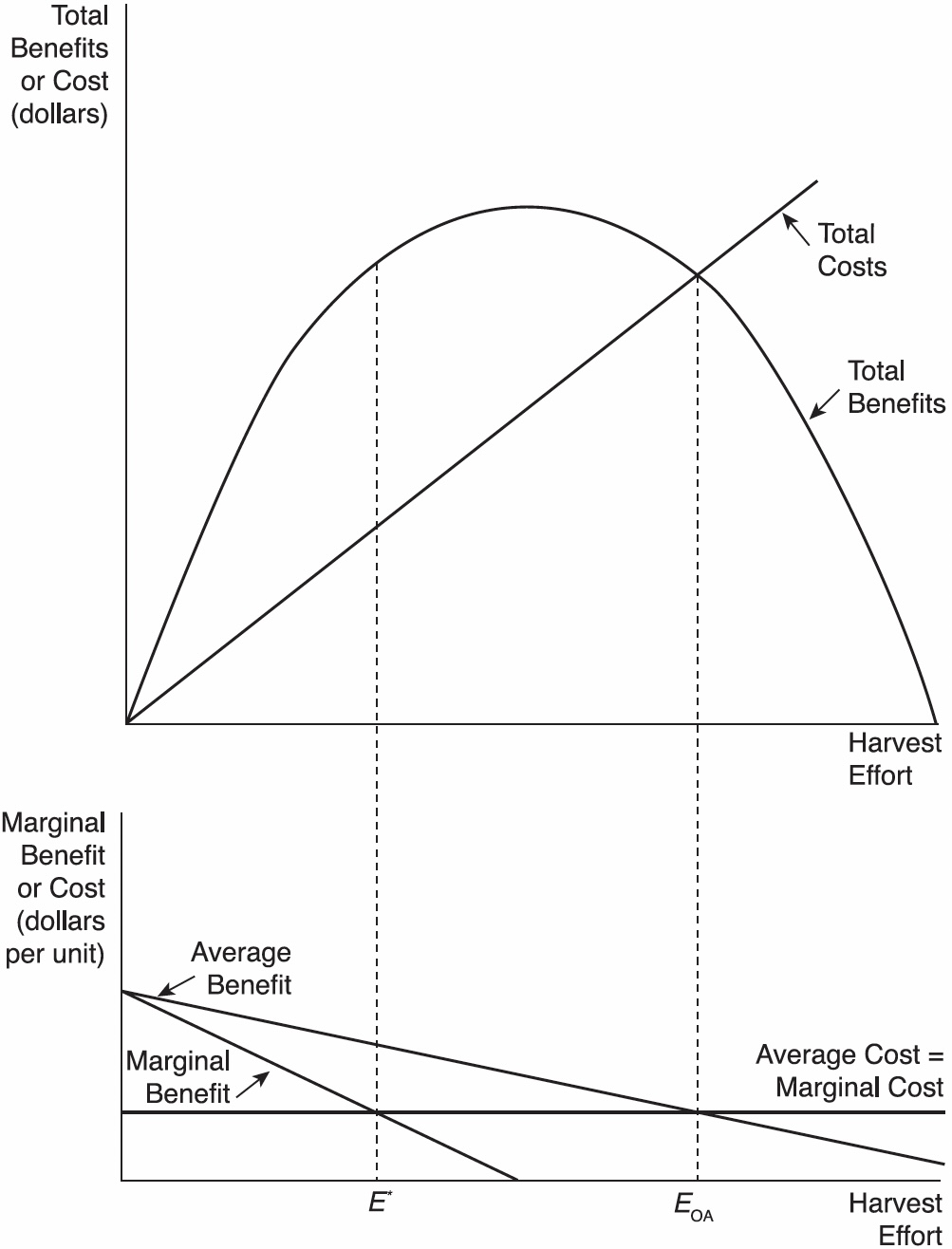

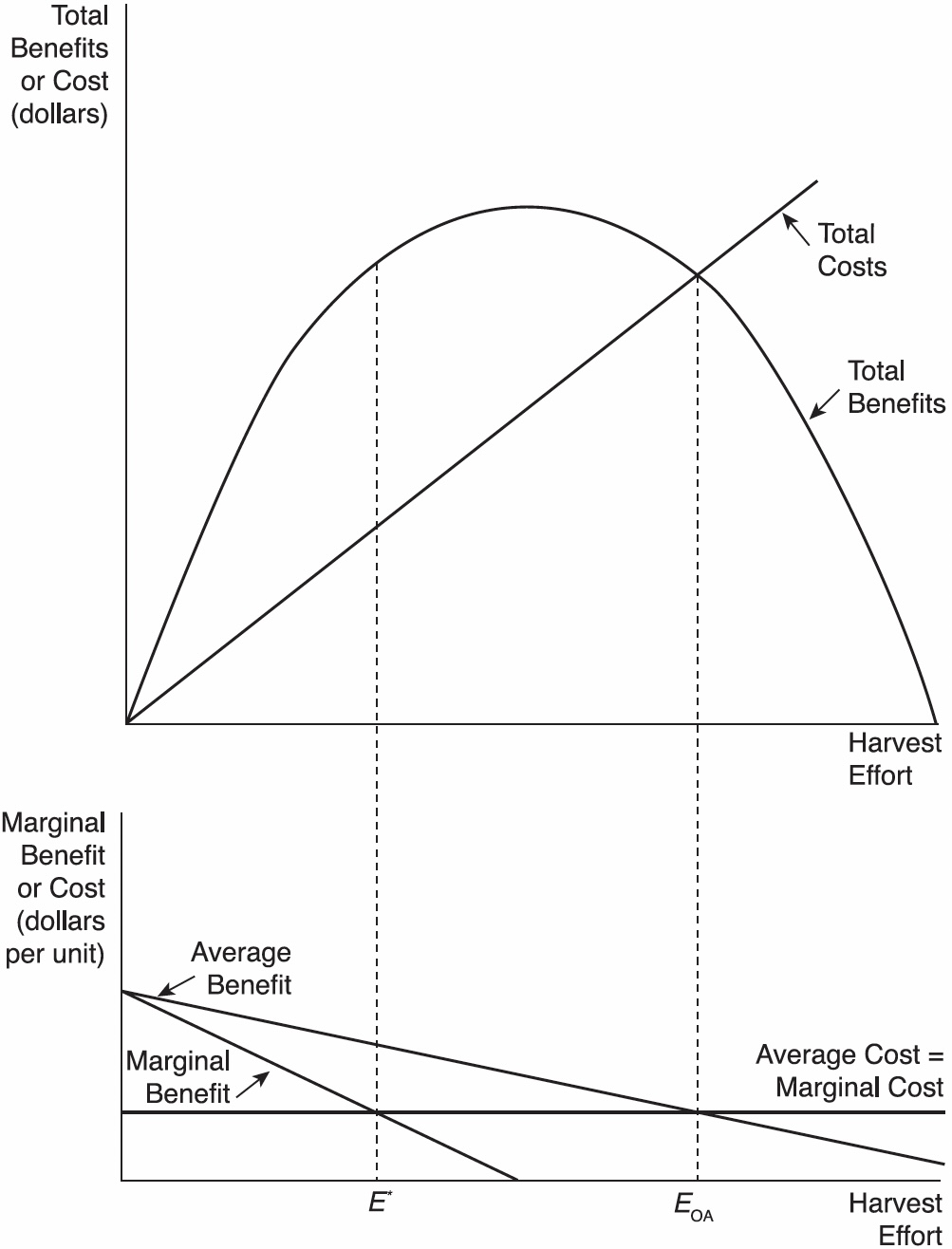

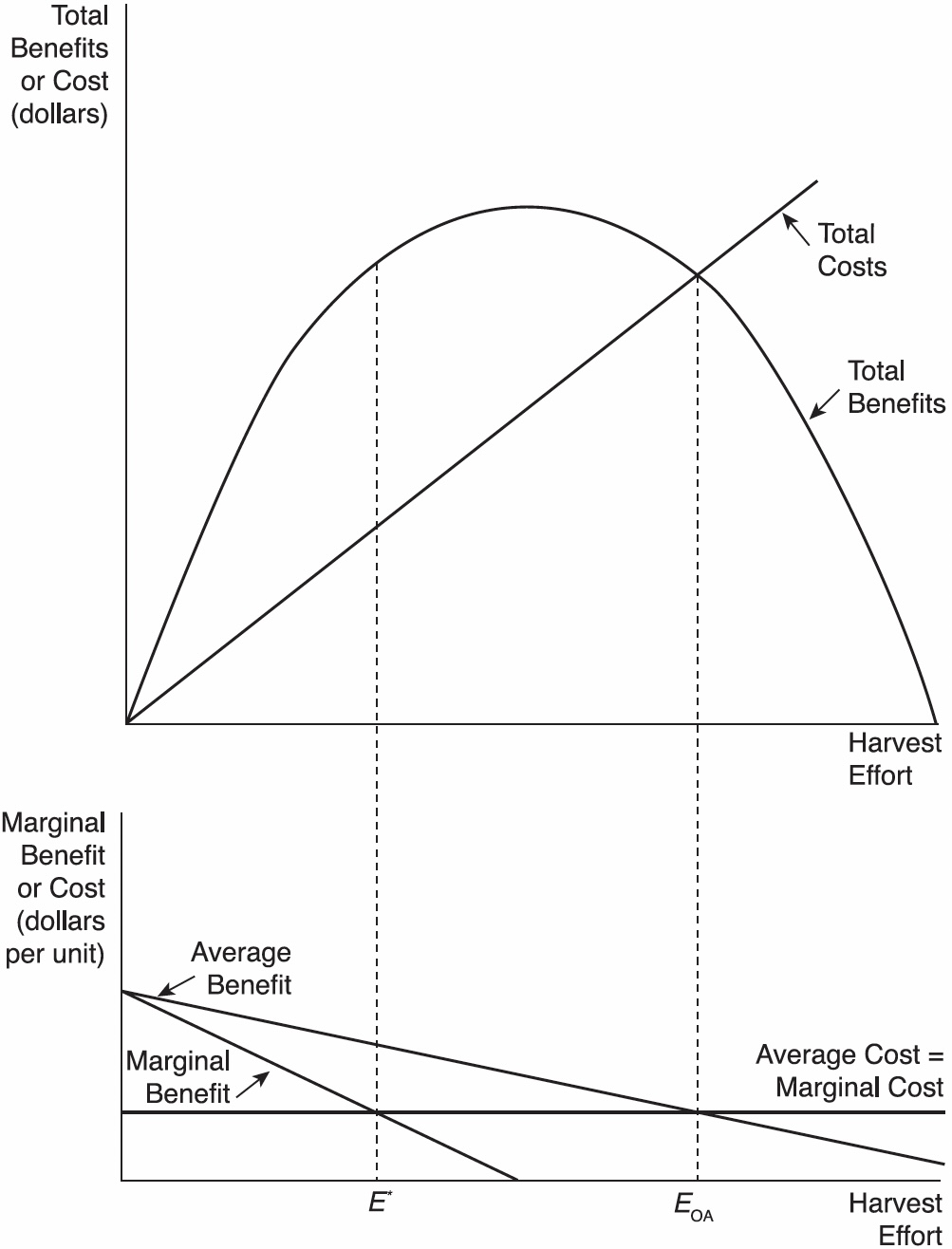

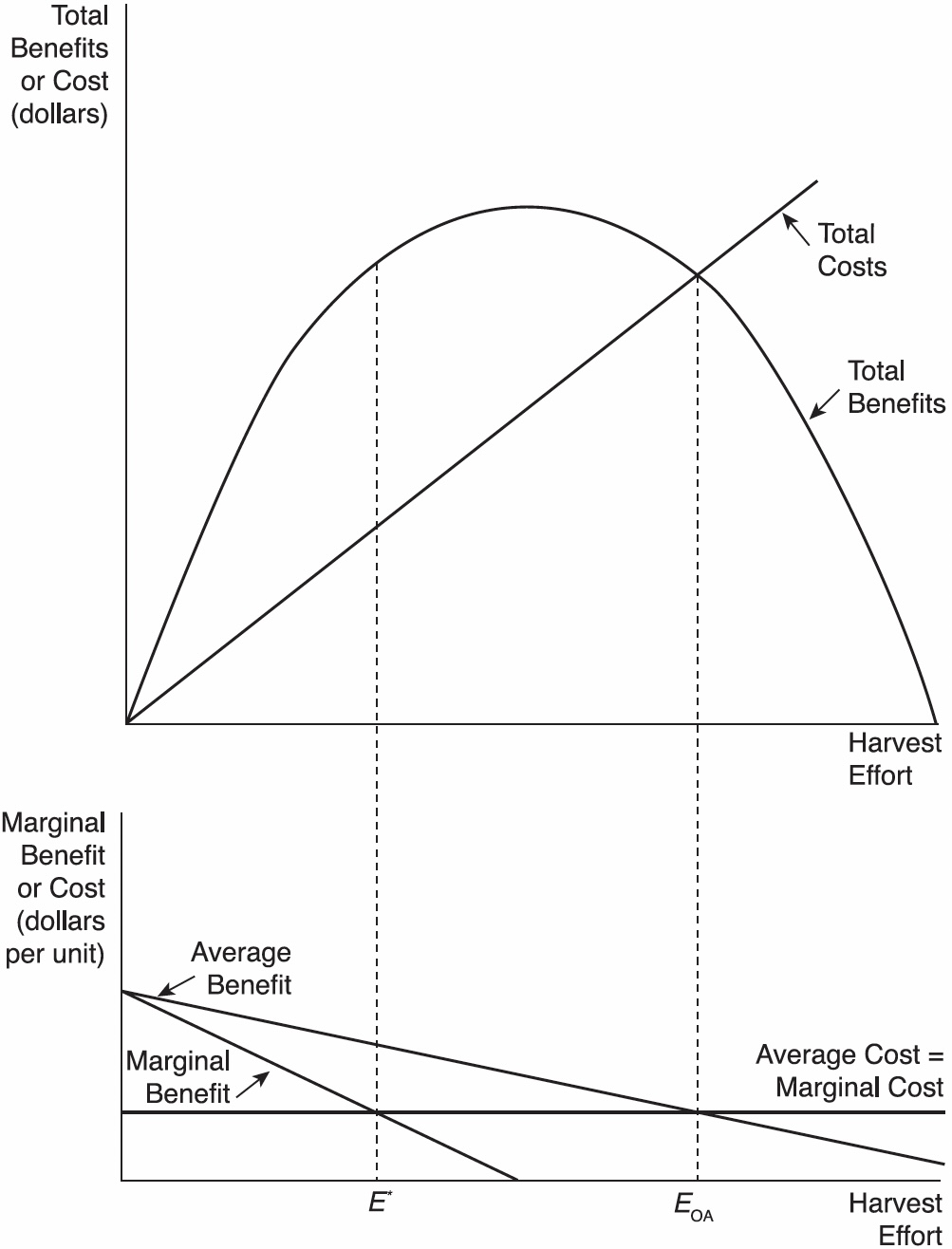

Total Framework (Top Panel)

- Total Surplus (Profit) \(TS(E) = TB(E) - TC(E)\).

- Total Benefit (Total Revenue) \(TB(E)\): increase with effort at a diminishing rate.

- Total Cost \(TC(E)\): increases with effort \(E\) (linear if marginal cost \(c\) is constant).

- Efficient effort \(E^{*}\): maximizes the vertical gap between \(TB\) and \(TC\).

Marginal Framework (Bottom Panel)

- Marginal Benefit \(MB(E) = \frac{dTB}{dE}\) declines as stock falls with effort.

- Marginal Cost \(MC(E)\) (e.g., constant \(c\)).

- Efficiency: \(MB(E^{*}) = MC(E^{*})\).

- Two panels are equivalent representations of the same optimum.

Locating the Efficient Point \(E^{*}\)

- In totals: \(E^{*}\) maximizes \(TB − TC\).

- In margins: \(MB = MC\).

- Interpretation: At \(E^{*}\), the last unit of effort adds as much revenue as it costs.

Open-Access Outcome \(E_{OA}\): Why It’s Too High

- Under free entry, effort keeps expanding until each user earns zero profit.

- The open-access condition is:

\[ AB(E_{OA}) = AC(E_{OA}) \]

- At this point (\(E = E_{OA}\)), Total Surplus (profit) is zero:

\[ \begin{align} TS(E_{OA}) &= 0\quad \Leftrightarrow \\ \frac{TB(E_{OA})}{E_{OA}} &= \frac{TC(E_{OA})}{E_{OA}} \end{align} \]

The Overuse Problem in Open Access

No exclusion ⇒ no one can secure surplus.

Each user ignores the stock externality imposed on others (and on the future).

With free entry, effort keeps expanding until per-user profit \(=0\).

- This drives total economic rent to zero.

Why does effort go too far?

- When total benefits (\(TB\)) flatten under diminishing returns, the average benefit (\(AB\)) stays above the marginal benefit (\(MB\)).

- Individuals follow the average, thinking it’s still worth entering (per-user profit \(>0\)).

- But efficiency depends on the marginal, which has already fallen.

- This mismatch keeps effort rising past the efficient level.

- When total benefits (\(TB\)) flatten under diminishing returns, the average benefit (\(AB\)) stays above the marginal benefit (\(MB\)).

Result: \(\;\;E_{OA} > E^{*}\) and all rents are dissipated.

Policy Tools to Fix Incentives

- Rights: Give people clear, fair rights to use the resource

- Could be private rights or strong common-property rules

- Rules & limits: Control who can enter and how much they can take

- Examples: licenses, quotas, individual transferable quotas (ITQs), seasonal closures, gear limits

- Backed up with good monitoring and enforcement

- Examples: licenses, quotas, individual transferable quotas (ITQs), seasonal closures, gear limits

- Prices & fees: Charge access or landing fees so users feel the true cost of overuse

- Use the money to fund stewardship (resource care) and support transitions for affected groups

- Capacity building: Help communities organize and cooperate

- Support user groups, resolve conflicts, and improve coordination between local and state levels

Community Governance of the Commons

- Beyond private property or top-down government rules, users themselves can create agreements to avoid the tragedy of the commons.

- Elinor Ostrom (Nobel Prize 2009) showed that many communities succeed through self-organization without needing full privatization or heavy state control.

- Challenged the “tragedy of the commons” idea: communities can manage shared resources.

- Showed real-world evidence (forests, fisheries, irrigation) where self-governance works.

Ostrom: Keys to Local Cooperation (I)

- Rules that fit the place: local users bring insider knowledge—about ecology, seasons, culture, customs, and technology—that outsiders often miss.

- Shared roles: community governance can work with government, especially for large resources.

- Example: federal agency runs ITQ program; local fishers co-design allocation rules and settle disputes.

- Participatory & scalable governance:

- Combine local (including Indigenous) knowledge, history, and culture with legal and scientific tools.

- At national/global scales, government still plays a role but must respect local variation and include community voices.

- Combine local (including Indigenous) knowledge, history, and culture with legal and scientific tools.

Ostrom: Keys to Local Cooperation (II)

- Precautionary rules: users see that short-term gains can cause long-term collapse, so they adopt protective rules.

- Monitoring with accountability: users check each other, or monitors report directly to the community.

- Graduated sanctions: small penalties for first violations, stronger ones for repeat rule-breaking.

- Monitoring with accountability: users check each other, or monitors report directly to the community.

- Simple, low-cost conflict resolution: problems can be solved quickly and fairly.

Global Commons - Russia’s “Peanut Hole”

- Location: A high seas area in the center of the Sea of Okhotsk, surrounded by Russia’s EEZ (Exclusive Economic Zone), which generally extends 200 nautical miles from a coastal state’s baselines.

- Significance:

- Previously a global common outside Russia’s jurisdiction.

- Known as the “Peanut Hole” due to its unique shape.

- Challenges:

- Overfishing by international fleets posed threats to fish stocks.

- Difficulty in coordinating sustainable management of resources in this area.

- Resolution: In 2014, Russia gained control of the “Peanut Hole” under UN Convention on LOS (Law of the Sea) provisions, integrating it into its EEZ.