Lecture 7

Public Goods

October 3, 2025

Public Goods

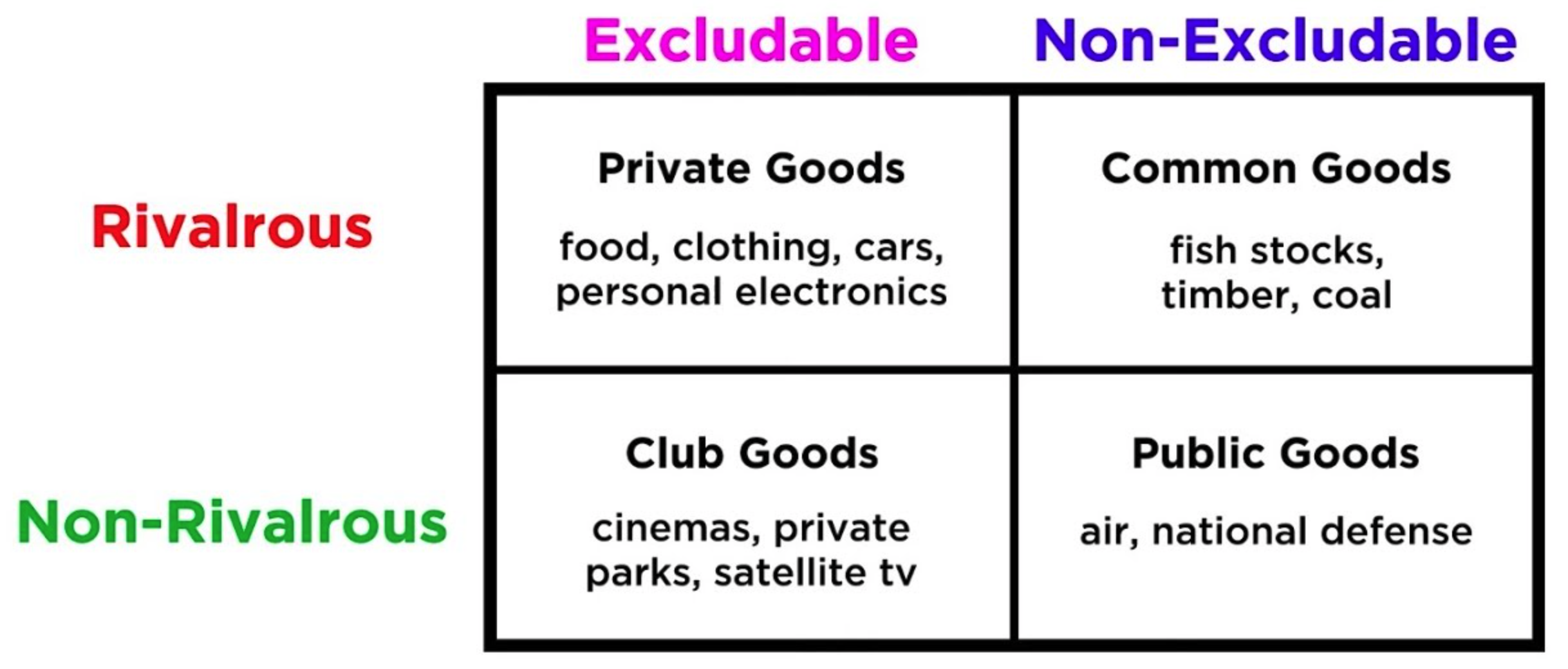

Rivalry & Excludability

Rival? Does one person’s use reduce what remains available for others?

Excludable? Can access be restricted to those who pay—or can anyone consume the good even without paying?

Where Do Public Goods Show Up in Energy & Climate?

- Basic R&D in energy efficiency, storage, fusion, green hydrogen (knowledge spillovers).

- Awareness campaigns on climate & energy saving.

- Protective infrastructure (often local public goods):

- Sea walls & surge barriers (coastal protection)

- Riverbank & floodplain defenses

- Urban heat mitigation (cool roofs, urban canopy)

- Global mitigation (e.g., CO₂ reduction benefits) vs. local adaptation (place-specific benefits).

Market Failures - Why Markets Underprovide Public Goods

- In competitive markets, demand = willingness to pay (WTP) for private goods.

- For public goods, individual WTP understates marginal benefit (MB) because people can consume even if they pay less (or nothing).

- Result: Free riding → \(\text{(Total Voluntary Funding)} \,<\,\text{(Cost)}\) → Underprovision.

Note

- Market failure here is on the demand side, unlike overuse of common-pool resources which is on the production side.

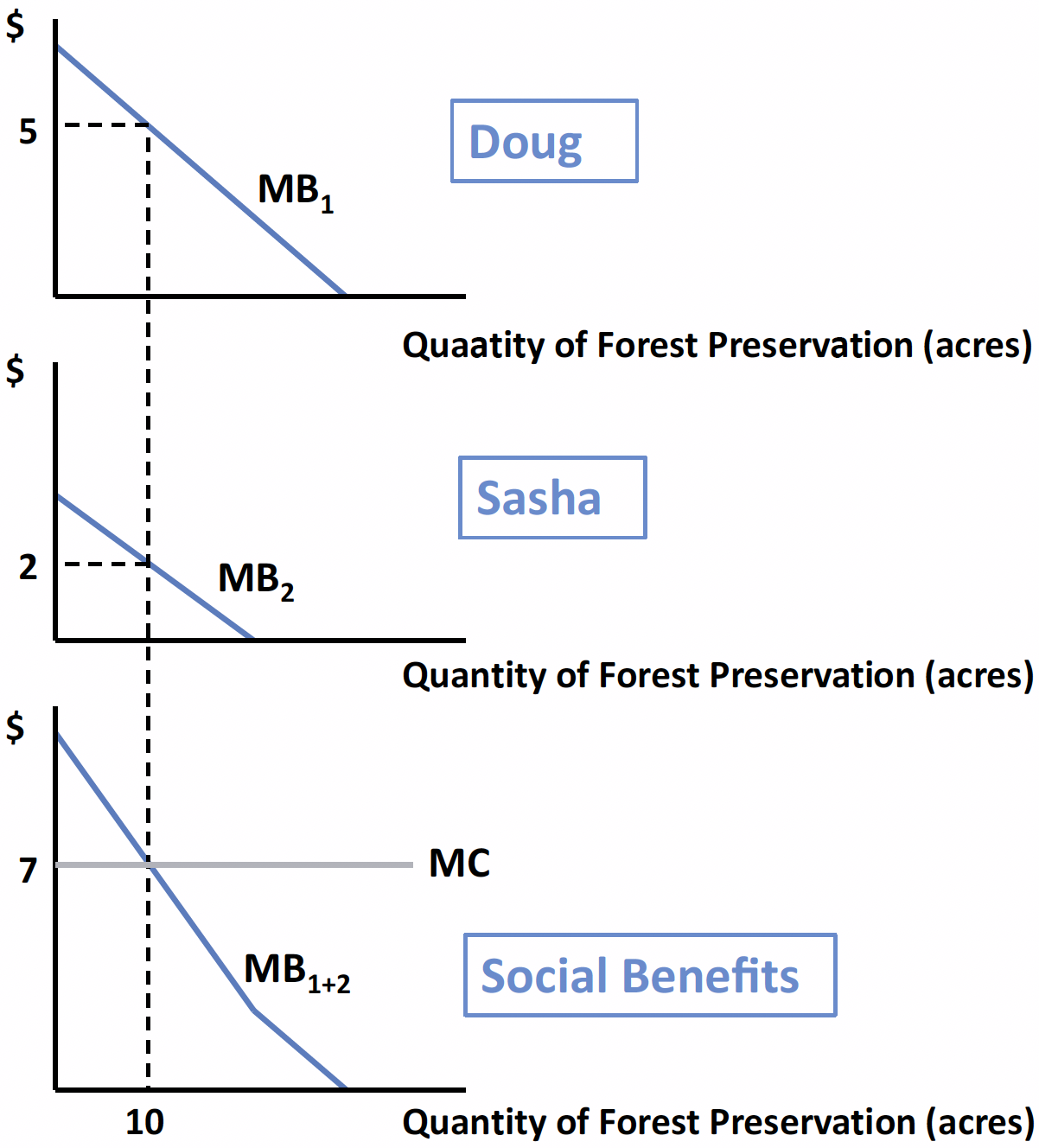

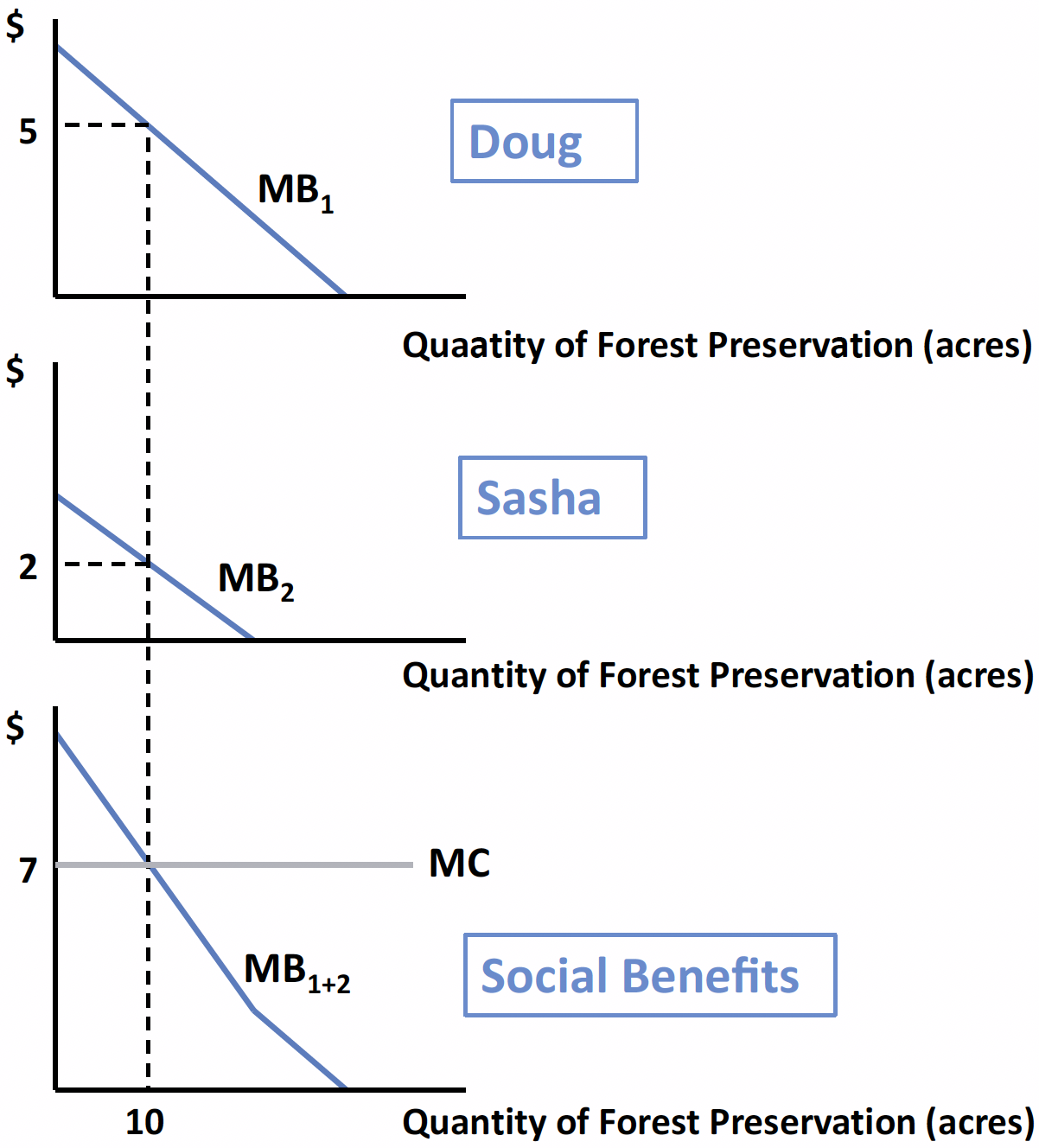

Aggregating Benefits: Vertical Summation

- Both value forest preservation (acres \(Q\)).

- At \(Q=10\), Doug’s \(MB\) = $5; Sasha’s \(MB\) = $2.

- For public goods, social marginal benefit (SMB) is the vertical sum of individual MB curves

- SMB = $7.

- Suppose SMC = $7 per acre (constant).

- Then \(Q^{*} = 10\) where SMB = SMC.

Funding the Optimum (Who Pays?)

- Total Cost = $70. Options:

- Uniform tax: Doug $35, Sasha $35 (simple, but ignores benefit differences).

- Benefit-based shares (ideal but hard to measure): Doug pays more since his MB is higher.

- Ability-to-pay: progressive finance to address equity concerns.

- Uniform tax: Doug $35, Sasha $35 (simple, but ignores benefit differences).

- Tensions:

- Efficiency: hit \(Q^{*}\).

- Fairness: how to split the bill?

- Efficiency: hit \(Q^{*}\).

Policy Tools - Direct Public Provision

Government directly provides the public good, funded through general taxation.

Avoids reliance on voluntary contributions → ensures adequate and stable supply.

Citizens share costs through taxes, but everyone benefits once the good is provided.

Examples:

- National defense

- Basic scientific research

- Public health campaigns (e.g., vaccination drives)

- National defense

Policy Tools - Matching grants & subsidies

- Amplify voluntary contributions by adding public funds

Encourages private giving, lowers cost of participation

- Examples:

- U.S. federal charitable gift matching programs (e.g., matching donations to conservation NGOs)

- Public broadcasting pledge drives with matching challenges

- State and federal subsidies for rooftop solar panels and energy-efficient appliances

- Local governments matching community fundraising for parks, libraries, or schools

- International funds (e.g., Green Climate Fund) co-financing climate adaptation projects with national contributions

- U.S. federal charitable gift matching programs (e.g., matching donations to conservation NGOs)

Policy Tools - Earmarked Taxes & Levies

Dedicated funding streams linked directly to a specific public good.

Revenues cannot be spent elsewhere → builds trust that taxes support the intended purpose.

Helps align costs with beneficiaries (those who pay are often those who benefit most).

Examples:

- Resilience bonds to finance disaster protection infrastructure

- Carbon levies to support climate mitigation and clean energy

- Local conservation assessments for parks, wetlands, or open space protection

- Resilience bonds to finance disaster protection infrastructure

Policy Tools - Patents & Prizes

- Provide incentives for innovation by making knowledge partly excludable.

- Patents: grant temporary monopoly rights to inventors → they can earn profits, encouraging investment in R&D.

- Prizes: reward specific breakthroughs without ongoing monopoly, while allowing broader diffusion.

- Both approaches aim to stimulate innovation while still creating knowledge spillovers that benefit society.

- Examples:

- Pharmaceutical patents for new drugs

- XPRIZE competitions (e.g., carbon removal, space technology)

- Government innovation prizes for energy efficiency or medical devices

- Pharmaceutical patents for new drugs

Policy Tools - Information & Social Norms

Use campaigns, education, and messaging to influence behavior and public attitudes.

Can shift social norms so that contributing to or supporting a public good becomes the default.

Works best when combined with other policy tools (taxes, subsidies, regulation).

Examples

- Climate awareness campaigns (e.g., “Act on Climate”)

- Energy-saving initiatives (“Turn off the lights,” Energy Star labeling)

- Public health messages (seatbelt use, anti-smoking, vaccination reminders)

- Recycling and waste reduction campaigns

- Climate awareness campaigns (e.g., “Act on Climate”)

Money Growing on Trees: Payments for Environmental Services in Community Forestry

Climate Change and Forests

- Climate change arises from net greenhouse gas emissions

- Abatement (mitigation) can come from

- ↓ Reducing sources — burning fewer fossil fuels

- ↑ Increasing sinks — forests that absorb CO₂

- ↓ Reducing sources — burning fewer fossil fuels

- Forests act as natural carbon storage

- “Avoiding deforestation” = negative emissions relative to baseline

Avoiding Deforestation: Economics of Abatement

- Social benefit: avoided climate damages (global public good)

- Social cost: opportunity cost of land or resources

- Lost agricultural income

- Lost timber or charcoal value

- Lost agricultural income

- Many tropical regions offer low-cost abatement opportunities

→ Why global climate finance often targets developing countries

REDD+ and PES

- Avoiding deforestation creates positive externalities

- Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES):

- Pay local households for the environmental services they provide

- Internalize the externality through incentive-compatible contracts

- Pay local households for the environmental services they provide

- Example: REDD+

- Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation

- \(+\) Sustainable forest management for carbon storage

Who Pays for PES Contracts?

- Polluters (firms or countries) are often required by regulation to limit their total emissions.

- Instead of cutting emissions directly, they can buy offsets, such as:

- “Protect 1 hectare of rainforest instead of emitting 100 tons of CO₂.”

- These offsets are integrated into cap-and-trade markets.

- Companies can choose between permits and offsets to meet emission limits.

- Companies can choose between permits and offsets to meet emission limits.

- International PES schemes therefore act as global offsets, transferring resources from high-emission (often rich) countries to low-income forest communities that conserve carbon sinks.

Why Is PES Hard?

Verifiability & Additionality

- Verifiability → Can we confirm the forest was truly protected?

- Avoids fraud and double counting

- Additionality → Would it have been protected anyway?

- Avoids non-additional payments

- Non-verifiable or non-additional contracts

→ Waste resources and fail to reduce total emissions

PES Role-Playing Game 🎲

You are a household in rural Ephoria, a low-income tropical country.

- Forest resources = subsistence + cash

- Government introduces a PES contract:

- Pay $50 if you agree not to harvest wood this year

- Each round = new policy design

- Pay $50 if you agree not to harvest wood this year

- Option A: Deforest

- Harvest wood for cooking or sale

vs.

- Option B: Conserve

- Accept PES payment

- Commit not to harvest

- Accept PES payment

Contract Periods (Treatments)

| Period | Policy Context | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Baseline | No PES (individual harvest only) |

| 1 | PES | Legal PES contracts only |

| 2 | PES + Illegal Harvest | Can cheat; subject to random audit |

| 3 | Community PES | Group decision and shared payment |

| 4 | Community + Illegal Harvest | Group and individual enforcement |

CP1 – Baseline vs. PES

How did you decide between harvesting and PES?

Did your card value affect your choice?

🧭 Concepts

- Opportunity cost (abatement cost)

- Additionality (True additional conservation only occurs when the payment changes behavior)

- Heterogeneity in cost → cost-effective targeting

CP2 – Illegal Harvest Option

You could sign PES but still harvest (“cheat”)

Small chance of being audited

If caught → lose payment + fine

🧠 Key Idea: Rational Theory of Crime (Becker 1968)

- Expected benefit of cheating =

(gain if not caught) − (probability × penalty)

- Expected benefit of cheating =

💭 What share of the class cheated? Why?

CP3 – Community Contract

Now, each community decides together whether to join PES

If accepted, PES payment must be shared among members

Split rules vary: equal, proportional, needs-based, etc.

🤝 Concepts

- Community governance (Ostrom)

- Fairness & equity norms

- Coordination vs. free-riding

- Community governance (Ostrom)

CP4 – Community Contract + Illegal Harvest

- Communities can join PES and decide whether to police

- If policing → cost $5 per household, no cheating possible

- If not → some may harvest illegally

- Audit probability increases with # illegal harvesters

- If policing → cost $5 per household, no cheating possible

- ⚖️ Concepts

- Self-governance

- Collective enforcement

- Trust & social capital

- Deterrence by monitoring

- Self-governance

🌳 The Promise of Forest-Based PES

- Aligns incentives: Encourages conservation by paying for the ecosystem services forests provide (carbon storage, biodiversity, water regulation).

- Cost-effective mitigation: Taps into low-cost abatement opportunities in developing regions — “climate finance with co-benefits.”

- Income diversification: Provides a stable cash flow to rural households that might otherwise rely on unsustainable logging or agriculture.

- Global–local partnership: Transfers resources from high-emission (often rich) countries to low-income communities maintaining forests.

- Flexibility: Can be scaled or customized — individual, community, or landscape-level programs.

⚠️ Potential Pitfalls and Challenges

Additionality problem

→ CP1 in our game shows how payments can reward non-additional conservation.Verification and enforcement

→ Illegal harvesting in CP2 and CP4 highlights the verifiability challenge.Leakage

→ Conservation in one area can shift deforestation to another.

→ Not captured in our classroom game, but critical in real programs.Equity and fairness

→ Who gets paid — landowners or landless users?

→ How are community payments shared (as in CP3–CP4)?

→ Risk of elite capture or exclusion of marginalized groups.Dependence on external funding

→ Long-term sustainability uncertain once donor support ends.

⚖️ Equity, Empowerment, and Governance

- PES can empower communities by recognizing their role in environmental stewardship — especially under community-based contracts (like CP3–CP4).

- However, unequal land rights and bargaining power can reinforce inequalities — wealthier households or leaders may capture the majority of benefits.

- Trust and local governance capacity determine whether PES fosters cooperation or conflict.

- The design of payment division rules (equal vs. proportional vs. needs-based) has real implications for fairness and motivation.

🧠 Discussion

- In our experiment, who gained most from PES — low-card or high-card players?

- Did community-level decision-making improve or reduce fairness?

- If you were a policymaker in Ephoria, how would you redesign PES to:

- Improve additionality,

- Strengthen compliance, and

- Ensure equitable benefit sharing?

- Improve additionality,

- 💬 Key takeaway:

PES succeeds not just when payments exist — but when they are credible, additional, verifiable, and fair.