Lecture 8

Information, Incentives, and Behavioral Anomalies

October 17, 2025

Market Failures

Sources of Market Failure

- Externalities — private decisions impose unpriced costs or benefits on others

- Public Goods & Common-Pool Resources — non-excludability leads to free-riding or overuse

- Lack of Competition — market power (monopoly or collusive oligopoly) distorts price and quantity

- Information Problems — imperfect or asymmetric information skews choices

- Principal–Agent Problems — split incentives between decision-maker and payer

- Behavioral Anomalies — bounded rationality, willpower, and social norms affect decisions

Information and Principal–Agent Problems

Information Problems — What & Why

Imperfect information — consumers lack clear and accurate information about energy-saving technologies (appliances, vehicles, buildings, heating systems) and energy-producing options such as solar.

Asymmetric information — sellers possess or selectively present information that buyers cannot easily verify or compare.

Consequence — leads to distorted decision-making, resulting in under-adoption of efficient technologies, misallocation of resources, and welfare loss.

Policy responses may include energy labels, public energy audits, neutral advisory services, and targeted information campaigns to correct these informational gaps.

Principal–Agent Problems (Split Incentives)

Setup: Building owner (agent) chooses efficiency/heating; tenant (principal) pays energy bills.

Externality: Owner’s choice → tenant’s energy costs & pollution.

Asymmetry: Tenants can’t observe full tech set/quality.

Outcomes

- Owners underinvest in efficient/heating upgrades (high capital expenditures; they don’t pay operating expenditures).

- Tenants & society lose (higher bills, greater emissions, slow progress in energy-efficient retrofits).

Policy fixes

- Mandatory energy certificates, disclosure

- Minimum efficiency standards

- Info on renewables/adaptation (e.g., shading, natural ventilation)

Behavioral Anomalies

Behavioral Anomalies — Overview

Behavioral anomalies explain why households and firms deviate from fully rational decision-making.

We categorize them into three systematic departures:

- Bounded rationality — limited cognitive processing and biased perception

- Bounded willpower — preferences for future outcomes do not translate into present actions

- Bounded self-interest — decisions shaped by fairness, altruism, and social norms

Note

- Outcome: Both households and firms tend to overweight upfront costs and undervalue future savings or efficiency gains, leading to underinvestment in energy-efficient and low-carbon technologies.

🧠 Bounded Rationality — Mechanisms

- Cognitive limitations in processing complex evaluations

- Loss aversion — losses are weighted more heavily than equivalent gains in decision-making

- Status quo bias — preference for keeping existing technology/behavior

- Endowment effect — greater value attached to what one already owns

- Status quo bias — preference for keeping existing technology/behavior

- Framing effects — decisions change depending on how information is presented

- Limited use of information due to:

- Limited attention to relevant attributes

- Limited salience of long-term operating costs

- Faulty priors/beliefs about what information matters

- Limited attention to relevant attributes

🧠 Bounded Rationality — Impacts

- Difficulty assessing lifetime costs of energy-consuming durables

- Underuse of available efficiency information due to low salience

- Reliance on heuristics instead of formal cost-benefit reasoning

- Inertia — continued use of outdated, inefficient technologies

⏳ Bounded Willpower — Experiment

Poll 1 — Now vs. Soon

- Be honest — which one feels better right now?

- Option A: Get $5 right now at checkout

- Option B: Get $8 credited to your account in 1 month

- Option A: Get $5 right now at checkout

Poll 2 — Soon vs. Later

- Now imagine both options happen in the future — same 1-month delay.

- Option C: Get $5 in 12 months

- Option D: Get $8 in 13 months

- Option C: Get $5 in 12 months

- Those who choose A in Poll 1 but D in Poll 2 reveal a time-inconsistent preference

- Their future selves would rather wait, but their present selves can’t resist immediate gratification.

⏳ Bounded Willpower — Mechanisms

Note

A discount rate reflects how much less individuals value future outcomes compared to immediate outcomes — similar to how an interest rate reflects the cost of waiting to receive money later rather than now, based on the time value of money.

- Myopia / Present Bias

- Individuals value the present disproportionately more than the future, applying a high discount rate to near-term outcomes and a lower rate to distant outcomes

- This causes the first few years of future benefits to be heavily undervalued, while upfront costs are felt fully with no discounting

- As a result, immediate costs dominate future benefits

⏳ Bounded Willpower — Impacts

- Present Bias causes a time inconsistency problem — future actions fail to align with one’s original optimal plan

- Environmental concern does not translate into efficient purchasing behavior

- Upfront cost is overweighted relative to long-term operating savings

- Adaptation and efficiency decisions are delayed or postponed

- Environmental concern does not translate into efficient purchasing behavior

🤝 Bounded Self-Interest — Mechanisms

- Altruism — willingness to act for social or environmental benefit without direct personal gain

- Fairness preferences — concern for equitable outcomes in energy and climate policy

- Social norms — behavior shaped by what is perceived as acceptable or common within peer groups

🤝 Bounded Self-Interest — Impacts

- Social comparison of energy use can reduce overconsumption

- Peer effects in technology adoption — visibility of efficient choices encourages diffusion

- Potential for positive spillovers through collective behavioral change

Behavioral Bias → Market Equilibrium

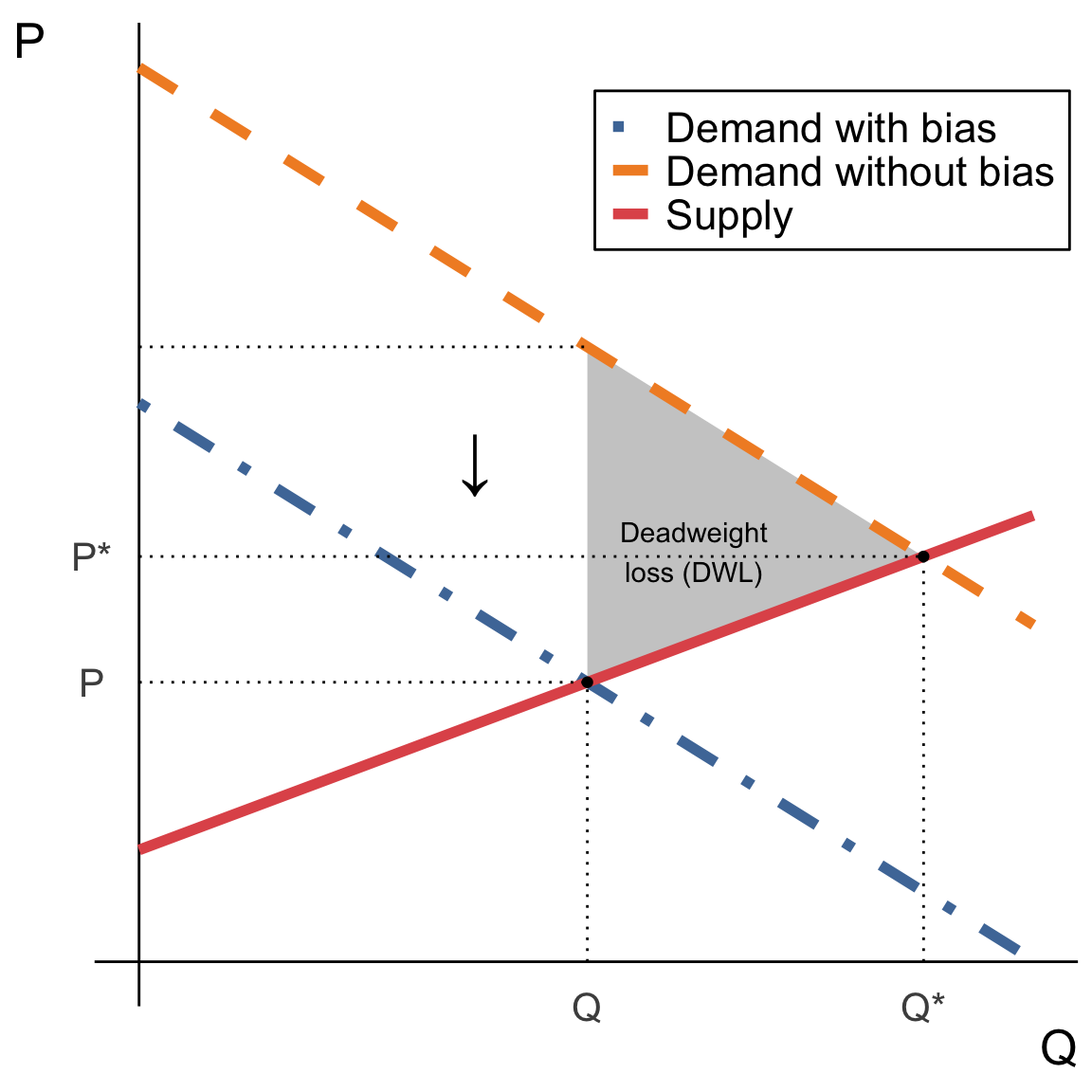

- Biases shift demand down for energy-efficient products (status quo, loss aversion).

- Equilibrium moves from (P*, Q*) (social optimum) to (P, Q) (biased market) with Q < Q*.

- Due to behavioral bias, how much welfare is lost relative to the rational, unbiased market outcome?

- Behavioral DWL here is the difference between potential surplus at Q* (with rational demand) and actual surplus at Q (with biased demand), using rational demand as the welfare benchmark.

Policy Design: Putting It Together

🎯 Policy Design: Putting It Together

To correct market failures, policy must integrate:

| 💰 Incentives | 🧠 Information | 🏛 Institutions | 🤝 Social Norms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Align financial signals with efficient choices | Make efficiency visible, comparable, and easy to act on | Set rules and structures that correct split incentives | Use peer effects and social signaling to shift behavior |

Effective policy design = Aligned incentives + Salient information + Supportive institutions + Reinforced social norms

Note

- Economics is fundamentally about policy design — improving human well-being through exchange and coordinated action by designing incentives, information, institutions, and social norms so that scarce resources and time are used more effectively.

💰 Incentives — Align Costs and Benefits

- Carbon / energy taxes — effective in theory but require attention to bounded rationality and present bias

- Should be paired with complementary decision aids (e.g., visible energy labels, default green options, or simplified prompts)

- On-bill financing — spreads costs over time by recovering investments through utility bills instead of requiring large upfront payments

- Performance-based contracts — repayment is tied to documented energy savings, reducing perceived risk

- Subsidies or rebates — more impactful when paired with salient, easy-to-understand information rather than passive financial incentives

🧠 Information — Make the Efficient Choice Obvious

- Energy labels with lifecycle cost information, not just efficiency class

- Standardized comparison tools — appliance efficiency rankings, certification platforms

- Real-time consumption feedback — smart meters, usage comparisons on bills

- Framing and default design — present efficient options as the default choice

- Public reporting of building or appliance energy performance

🏛 Institutions — Rules and Market Governance

- Minimum Energy Performance Standards (MEPS) — remove worst-performing products

- Building codes — enforce baseline energy efficiency and retrofit standards

- Green leases — contractually align landlord–tenant incentives

- Cost-sharing rule: Landlord installs efficient system; tenant agrees to slight rent premium.

- Energy savings clause: Rent adjustment linked to verified energy savings.

- Submetering requirement: Energy billing based on individual usage.

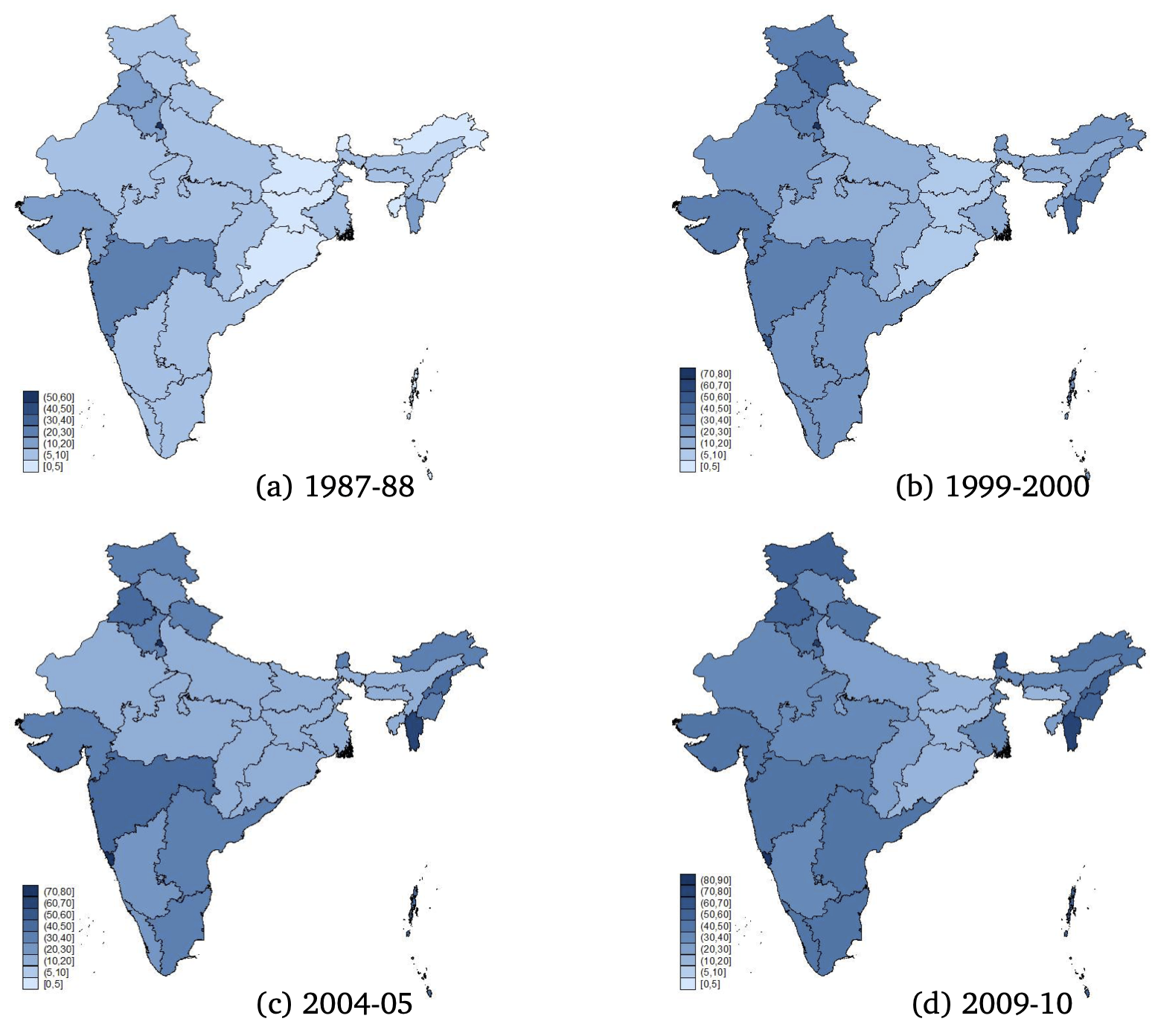

🤝 Social Norms in Action — LPG Adoption in India

- In many developing regions, households continue using firewood and biomass, leading to indoor air pollution and health risks.

- Adoption of cleaner LPG fuel rises significantly when neighboring households or members of the same social network have already adopted it.

Peer visibility and social spillovers act as positive social norms, speeding up the transition to clean energy.

Policy insight: Support energy transitions by activating community-level adoption signals, not only through prices or information.

🤝 Social Norms — Activate Peer Effects