Lecture 3

Property Rights, Externalities, and Natural Resource Problems

August 28, 2024

The Economic Approach: Property Rights, Externalities, and Natural Resource Problems

Introduction

- This chapter introduces the general conceptual framework used in economics to approach environmental problems.

- Static Efficiency

- Economic Surplus, Consumer Surplus, Producer Surplus

- Property Rights

- Scarcity Rents

- Externalities

- Public Goods

The Economic Approach

Positive Economics: Describing what is, what was and what will be.

Normative Economics: Attempting to answer what ought to be.

While these two types of analysis are conceptually distinct, they often inform each other.

The Economic Approach

Economic Impacts of Reducing Hazardous Pollutant Emissions from Iron and Steel Foundries

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) developed a “control technology standard” to reduce hazardous air pollutant emissions from iron and steel foundries.

How large would the impacts of the standard on production cost at affected facilities?

The Economic Approach

Economic Impacts of Reducing Hazardous Pollutant Emissions from Iron and Steel Foundries

The rule would increase production costs by $21.73 million annually for existing sources.

The analysis projected small price increases: 0.1% for iron castings and 0.05% for steel castings.

Iron foundries using cupola furnaces and consumers of iron foundry products would experience the primary impact.

The analysis showed the impacts were below the $100 million threshold, avoiding the need for an extensive review by the Office of Management and Budget.

The findings helped reduce opposition by demonstrating the minimal expected economic impacts.

Economic Efficiency

Static Efficiency

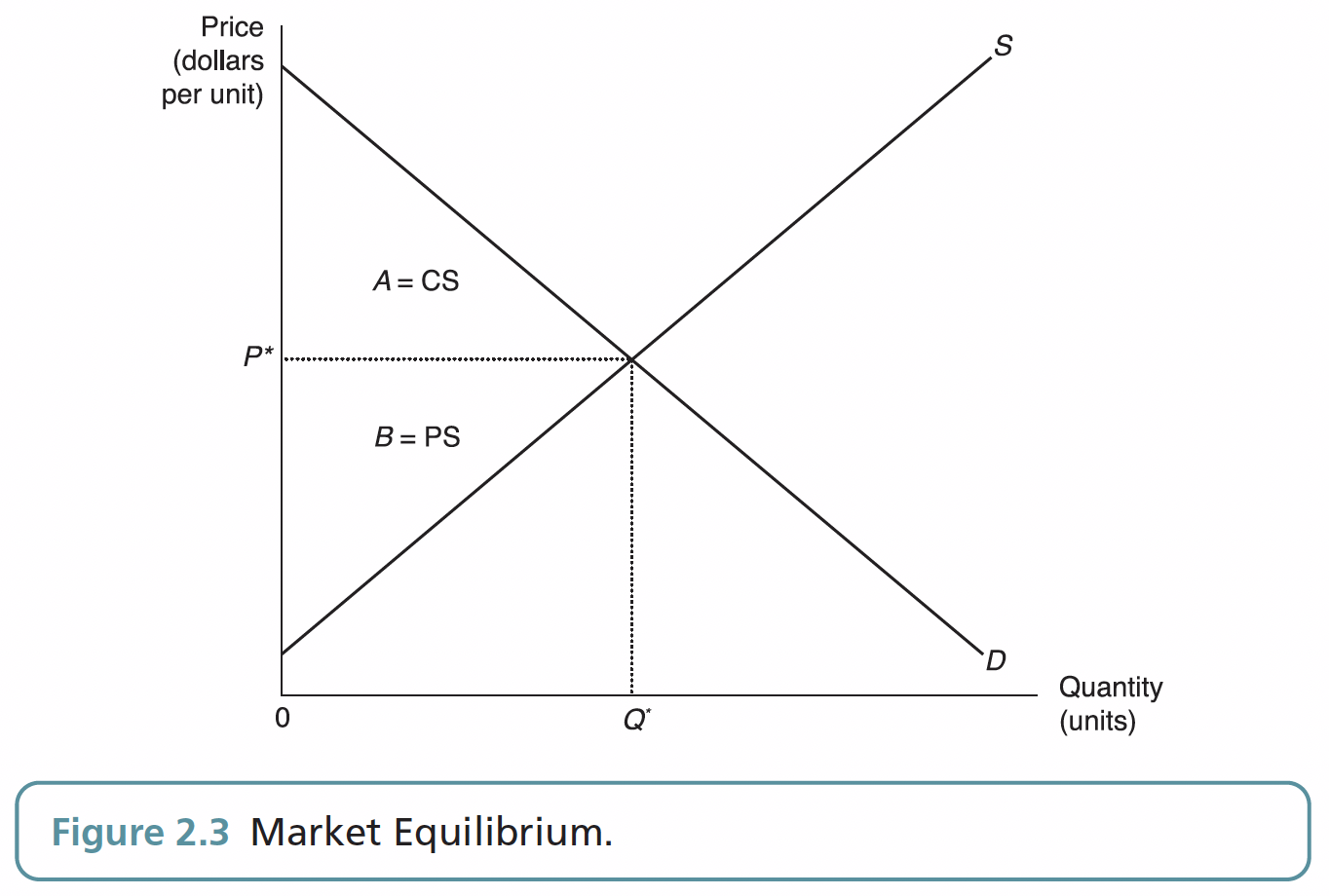

\[ \text{(Economic Surplus)} \,=\, \text{(Consumer Surplus)} \,+\, \text{(Producer Surplus)} \]

- An allocation of resources satisfies the static efficiency criterion if the economic surplus derived from those resources is maximized by that allocation.

Economic Efficiency

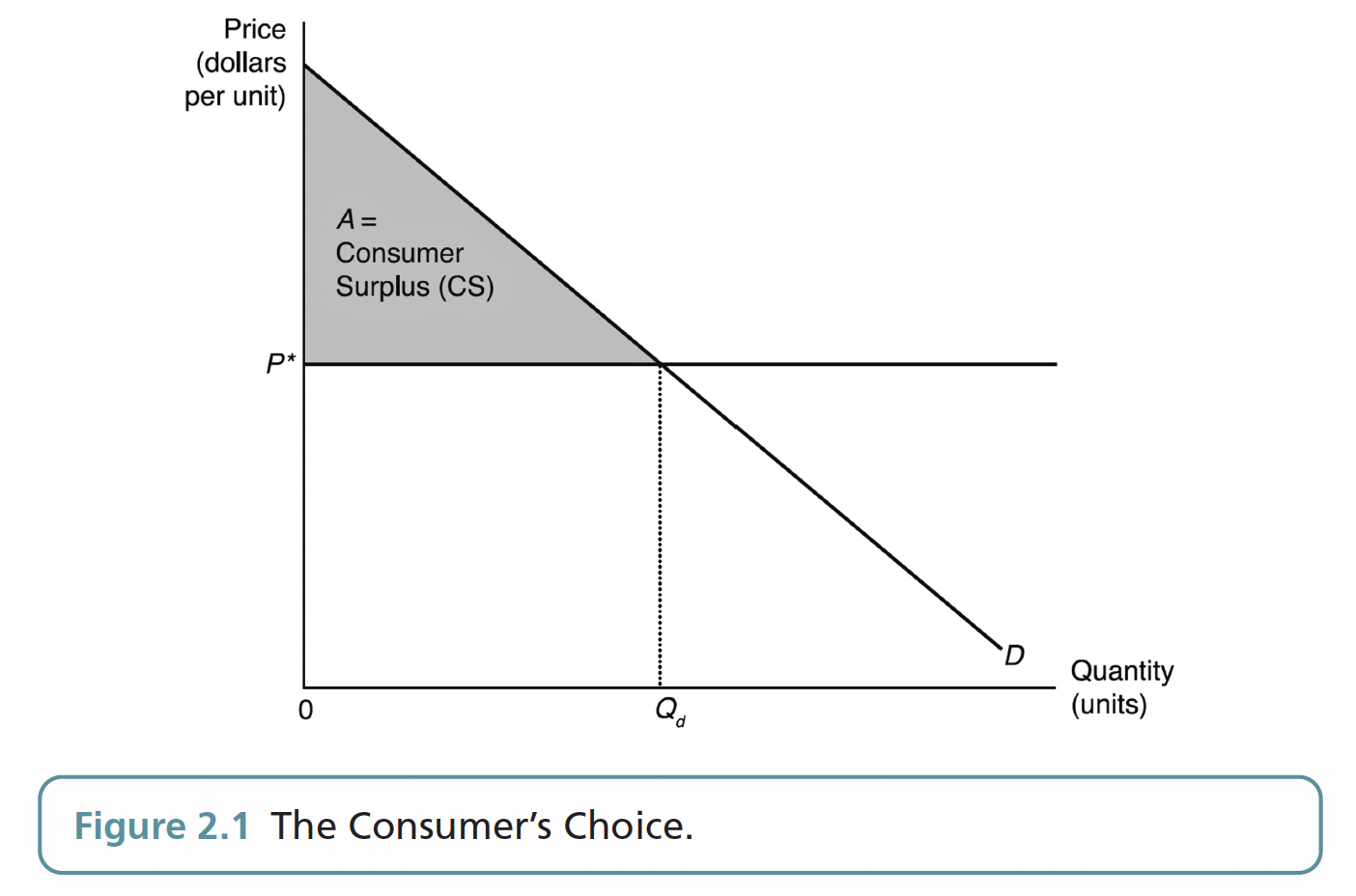

Consumer Surplus (CS)

CS is the value that consumers receive from an allocation minus what it costs them.

CS is measured as the area under the demand curve minus the consumer’s cost.

- Why?

Economic Efficiency

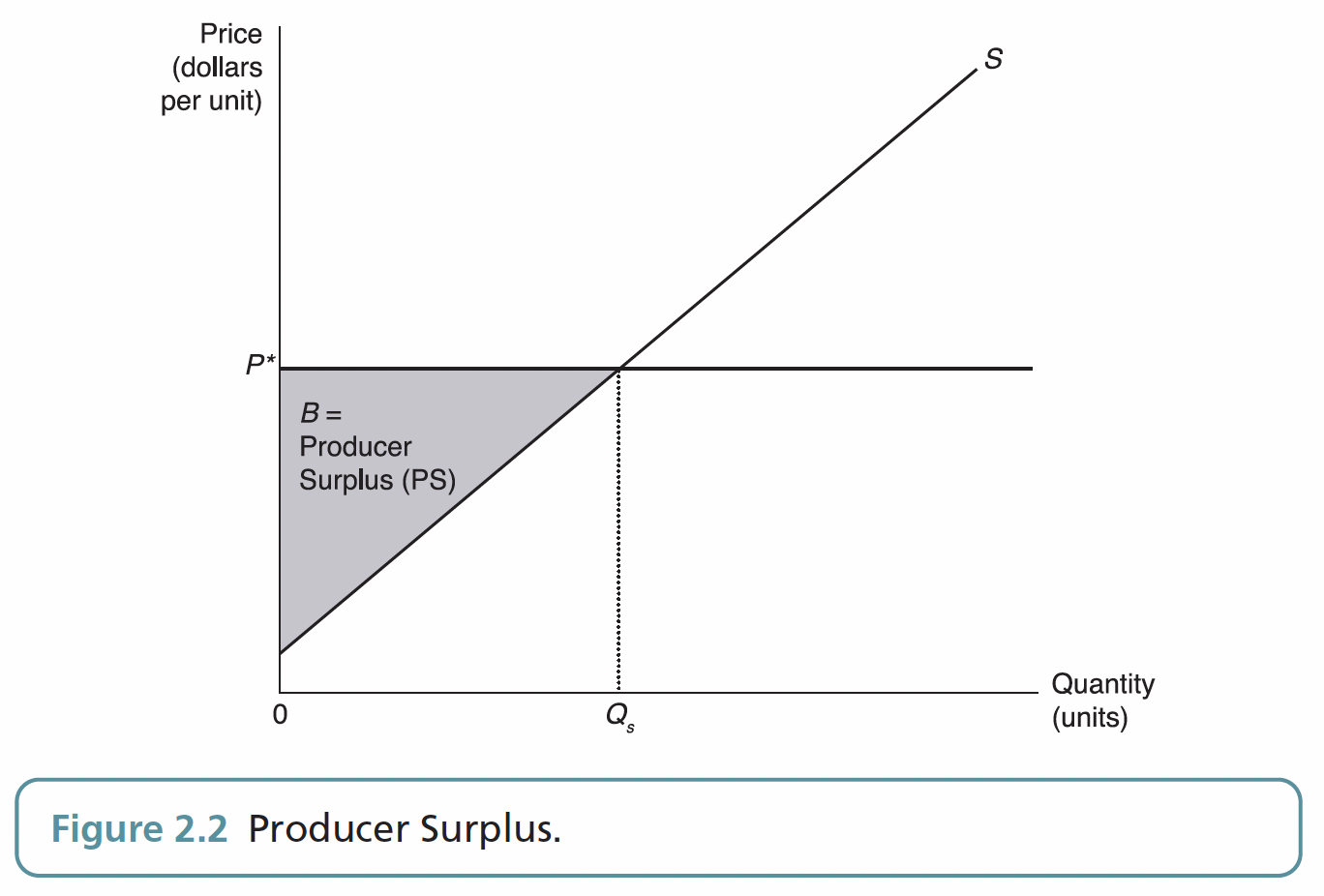

Producer Surplus (PS)

PS is the difference between the amount that a seller receives minus what the seller would be willing to accept for the good

PS is the area under the price line that lies above the supply curve.

- Why?

Economic Efficiency

Review on MC/MB curves

- In a perfectly competitive market, a marginal benefit (\(MB\)) curve is essentially synonymous with a demand curve.

- Each point on the demand curve represents the maximum price a consumer is willing to pay for a specific quantity of the good.

- This willingness to pay is directly related to the \(MB\) of the next unit of the good.

- Consumers are willing to buy an additional unit of a good only if the \(MB\) of that unit is greater than or equal to its price.

- The \(MB\) curve shows how many units consumers are willing to purchase at each price, which is the demand curve.

- In a perfectly competitive market, a firm’s marginal cost (\(MC\)) curve can be thought of as its supply curve:

- \(MC\) is a cost of producing one more unit of a good.

- Firms aim to maximize profit by producing where \(MC\) equals marginal revenue (\(MR\)).

- The market price (\(P\)) that a firm can charge for its product is determined by the market and is equal to its \(MR\).

- Therefore, the firms produce the quantity where \(MC\) equals \(P\).

- The \(MC\) curve directly determines how much the firms will supply at any given price.

Property Rights

Property Rights and Efficient Market Allocations

- Property rights refers to a bundle of entitlements defining the owner’s rights, privileges, and limitations for use of the resource.

- Can be vested in individuals, firms, or the state.

- Understanding property rights allows us to better understand how natural resource problems arise from government and market allocations.

Property Rights

Efficient Property Right Structures

Exclusivity: All the benefits and costs should only accrue to the owner.

Transferability: Property rights should be transferred to others.

Enforceability: Property rights should be secure from seizure or encroachment.

Property Rights

Efficient Property Right Structures

- In a system with well-defined property rights and competitive markets in which to sell those rights, the actions of self-interested individuals will result in an efficient equilibrium.

Property Rights

Water Rights in Agriculture

- Consider a region where water is a scarce natural resource, and there are well-defined property rights for water usage, particularly among farmers in agricultural production.

- In this region, a competitive market exists where these water rights can be bought and sold.

Property Rights

Water Rights in Agriculture

- Farmers hold water rights and aim to maximize their surplus by using water efficiently to grow crops that yield the highest profit.

- If a particular farmer finds that selling a portion of their water rights in the market would yield a higher return than using that water for low-value crops, they may choose to sell.

- Other farmers or industries in the region, needing water for higher-value crops or more profitable uses, are willing to buy water rights.

- They seek to maximize their surplus by obtaining water that enables them to produce more efficiently or profitably.

- The price of water rights reflects the supply and demand for water.

- As self-interested farmers sell or buy water rights based on their own profit-maximizing decisions, water is allocated to its most valuable use.

Property Rights

PS, Scarcity Rent, and Long-Run Competitive Equilibrium

In the short-run, \[ \overbrace{PS}^{\text{Producer}\\\,\text{ Surplus}} \,=\, \overbrace{\Pi}^{\text{Profits}} + \overbrace{FC}^{\text{Fixed}\\\,\text{Cost}} \]

This is because: \[ \begin{align} \overbrace{\Pi}^{\text{Profits}} &\,=\, \overbrace{TR}^{\text{Total Revenue}} \,–\, \overbrace{VC}^{\text{Variable}\\\;\;\text{Cost}} \,–\, \overbrace{FC}^{\text{Fixed}\\\,\text{Cost}}\\ \quad\\ \underbrace{PS}_{\text{Producer}\\\,\text{ Surplus}} &\,=\, \underbrace{TR}_{\text{Total Revenue}} \,–\, \underbrace{VC}_{\text{Variable}\\\;\;\text{Cost}} \end{align} \]

Thus, \(PS \,=\, \Pi + FC\) in the short-run.

Property Rights

PS, Scarcity Rent, and Long-Run Competitive Equilibrium

In the long run, \[ \overbrace{PS}^{\text{Producer}\\\,\text{ Surplus}} \,=\, \overbrace{\Pi}^{\text{Profit}} \,+\, \text{(Rent)} \]

\(\text{Rent}\): return to scarce inputs owned by the producer.

Under perfect competition,

- Long-run profits equal zero;

- Any \(PS\) in natural resource industries in the long-run equals rent.

This \(PS\) in long-run equilibrium is called scarcity rent.

- Cannot be eliminated by competition due to scarcity of natural resources.

Property Rights

Scarcity Rents in New England Fisheries

Data suggest that fishing off the New England coast would need be reduced by about 70% to eliminate overfishing and achieve an efficient harvest.

This would generate a scarcity rent of about $130 million.

If this were collected by the government, it would be sufficient to compensate those boats put out of business due to fishing restrictions.