Lecture 31

Common-Pool Resources: Commercially Valuable Fisheries

December 2, 2024

Course Summary

Student Course Evaluation (SCE)

- I have tried to improve your learning experience in this course.

- I value your feedback immensely.

- I request for your participation in the Student Course Evaluation (SCE).

- Take 10 minutes right now to complete the SCE.

- On your laptop, access the SCE form for ECON 341 as follows:

- Log in to Knightweb

- Click on the “Surveys” option

- Choose ECON 341 (class for which you want to fill out the SCE) and then complete the SCE survey.

Common-Pool Resources: Commercially Valuable Fisheries

Commercially Valuable Fisheries

In 2009, the World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) released a report called The Sunken Billions: The Economic Justification for Fisheries Reform.

The controlled raising and harvesting of fish is called aquaculture.

Commercially Valuable Fisheries

- Economic and Market Context:

- Marine capture seafood accounts for 20% of the $400 billion global food fish market.

- Downward pressure on producer prices due to:

- Market power of processors and retailers.

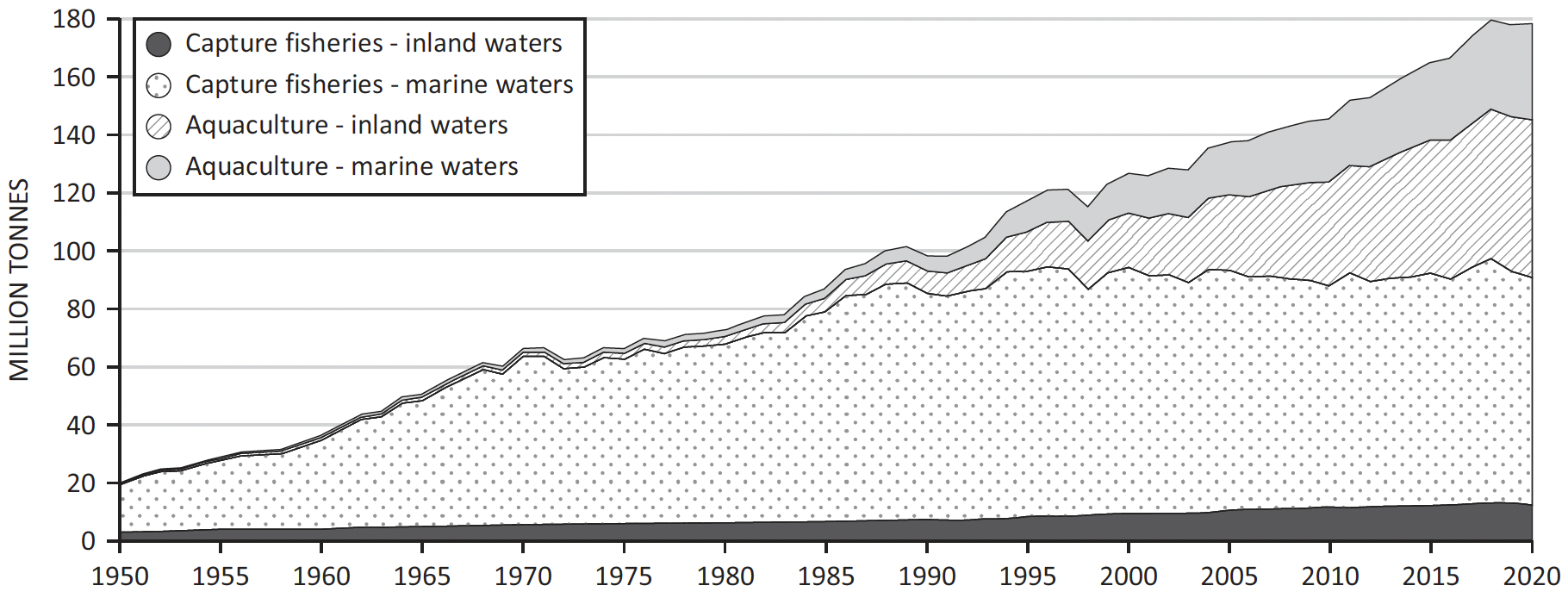

- Growth of aquaculture (now 50% of food fish production).

- Economic Losses: Approximately $50 billion per year due to overfishing, poor management, and economic inefficiency.

- Over the last 30 years, losses sum to over $2 trillion.

- Potential for Reform:

- Well-managed marine fisheries could provide sustainable economic benefits.

- Supports millions of fishers, coastal villages, and cities.

Human Interaction with Biological Populations

- Commercial Value:

- Provides strong reason for human concern about future of species.

- May promote excessive harvest leading to overexploitation.

- Institutional Frameworks:

- Influence conservation incentives.

- Crucial for protecting resources.

Key Renewable Resource-Management Issues

- Choosing Sustainable Harvest Levels:

- How do we choose among sustainable levels of harvest?

- What sustainable level of harvest is appropriate?

- Interactive Resources:

- Stock size determined by biological considerations and societal actions.

- Today’s actions affect future resource availability.

Efficient and Sustainable Harvest Levels

- Efficiency vs. Sustainability:

- Will efficient harvests always result in sustainable outcomes?

- Efficiency involves maximizing net benefits from resource use.

- Institutional Fulfillment:

- Do current institutions provide incentives compatible with efficiency and sustainability?

- Many normal incentives are incompatible, leading to overharvesting.

Overharvesting and Common-Pool Resources

- Open-Access Fisheries:

- Many commercial fisheries are open-access common-pool resources.

- Suffer from overexploitation due to lack of exclusive rights.

- Global Fisheries Status (FAO, 2021):

- Total fisheries and aquaculture production reached 214 million metric tons in 2020.

- 92% of fish stocks are fully exploited or overexploited.

- 35.4% of global stocks are overfished.

Tragedy of the Commons

Definition: The overuse and depletion of a shared resource when individuals prioritize their own self-interest over the collective good.

Key Cause: Personal benefits from exploitation are immediate, while the costs are shared across all users.

Challenges:

- Lack of effective institutions prevents resource asset value from being protected.

- Leads to overuse, depletion, and long-term economic and environmental harm.

Solutions:

- Develop strategies that balance efficiency with sustainability.

- Implement institutional reforms to address issues like overfishing and ensure equitable resource management.

Efficient Allocations—Bioeconomics Theory

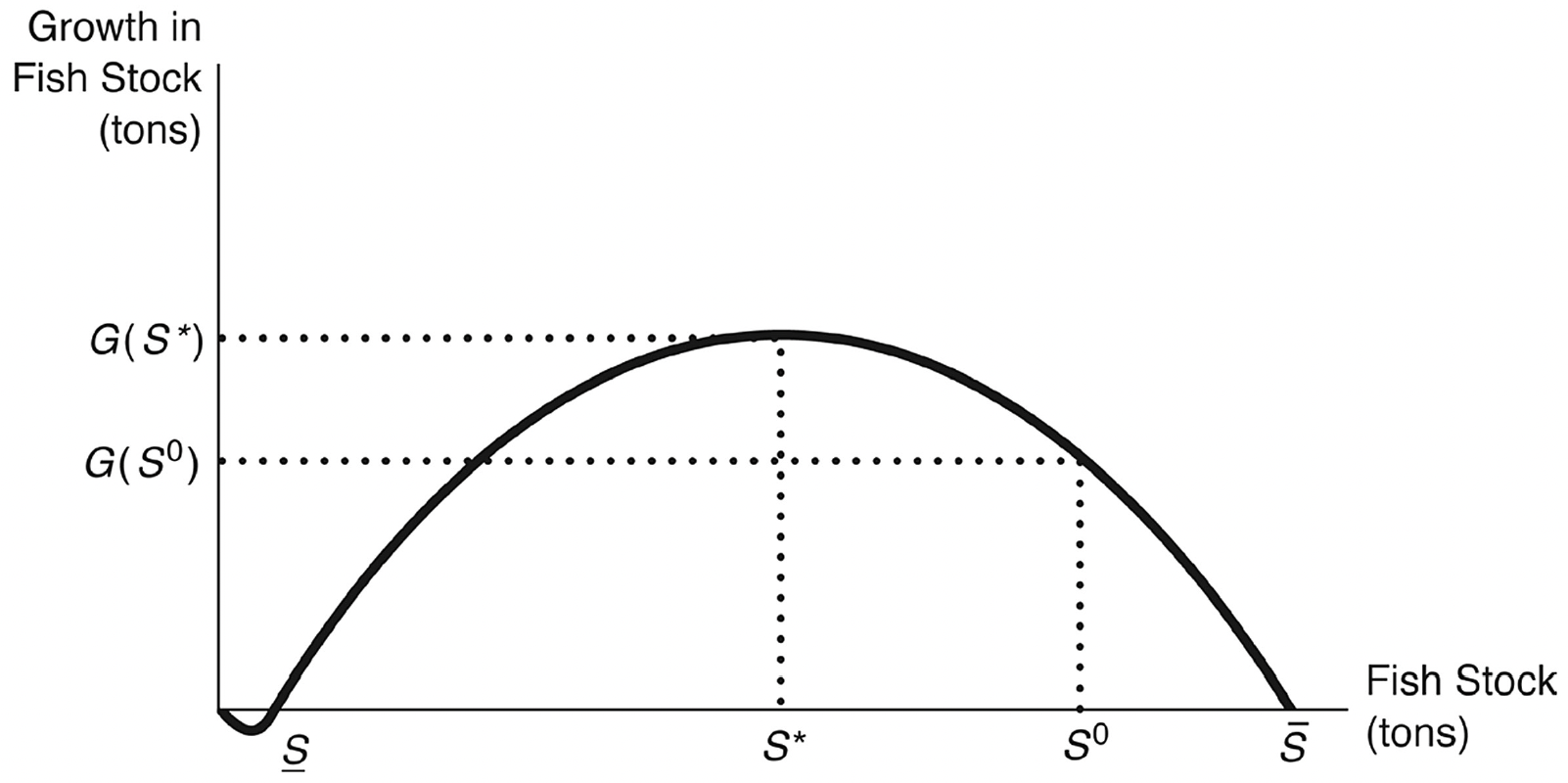

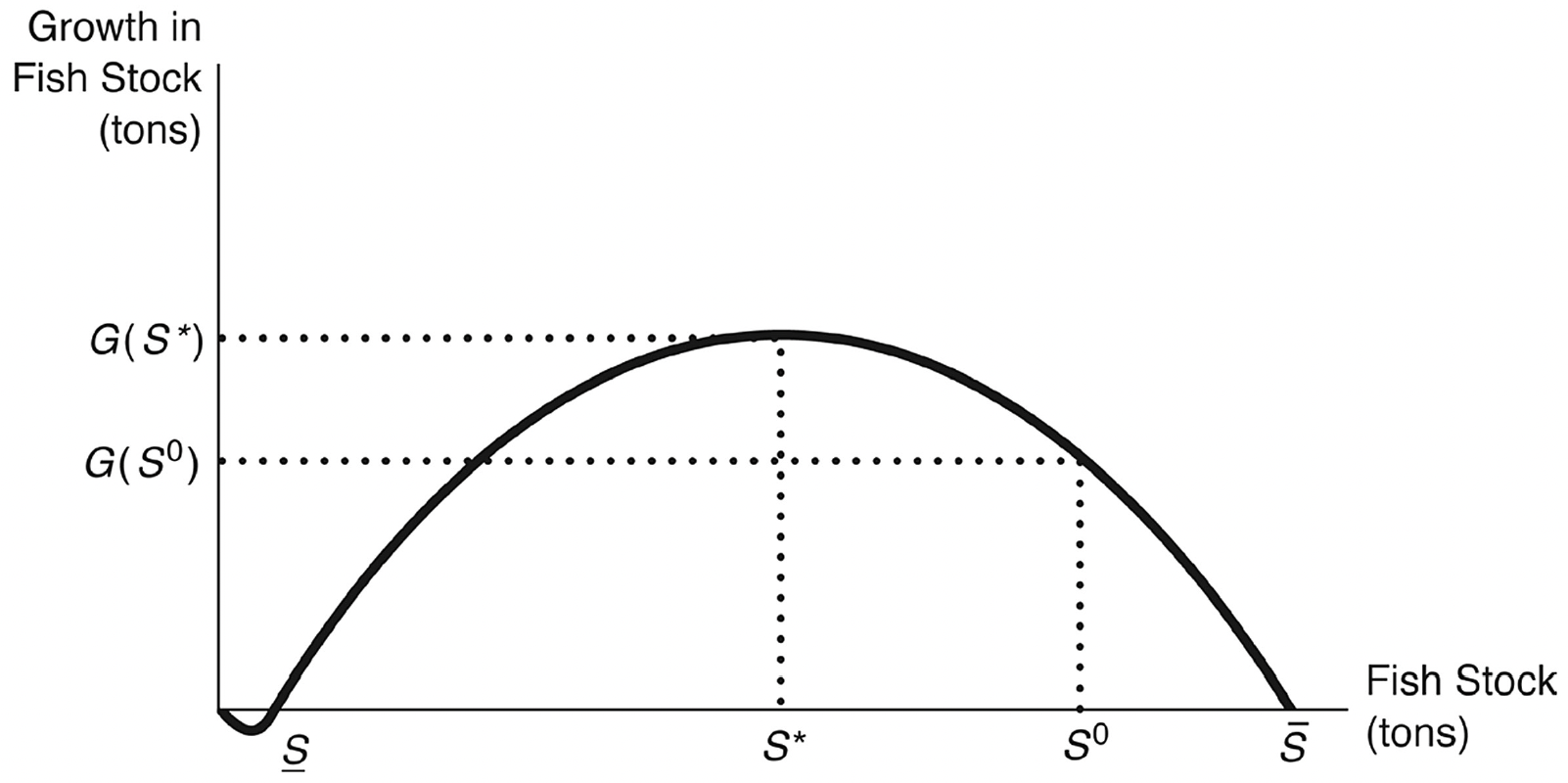

- \(S^{*}\): Maximum Sustainable Yield (MSY) Population.

- Population size yielding maximum growth.

- Corresponds to the largest sustainable catch.

- \(\overline{S}\): Natural Equilibrium (Carrying Capacity).

- Population size without external influences.

- Stable Equilibrium: Movements away set forces to restore it.

- \(\underline{S}\): Minimum Viable Population.

- Below this, growth is negative; population declines to extinction.

- Unstable Equilibrium.

Sustainable Yield

\(G(S_{0})\): the sustainable yield for population size \(S_{0}\).

- Since the catch is equal to the growth, population size (and next year’s growth) remains the same.

- Definition:

- Catch equals the growth of the population.

- Can be maintained perpetually.

- Determining Sustainable Yield:

- For any population size between \(\underline{S}\) and \(\overline{S}\), sustainable yield is found where catch equals growth.

Static Efficient Sustainable Yield

- Is MSY Efficient?:

- No, because efficiency involves net benefits, not just maximum catch.

- Static Efficient Sustainable Yield:

- Catch level that, if maintained perpetually, maximizes annual net benefit (benefits minus costs).

Economic Model Assumptions

- Constant Price of Fish:

- Price does not depend on the amount sold.

- Constant Marginal Cost of Fishing Effort:

- Cost per unit of effort is constant.

- Catch per Unit Effort Proportional to Population Size:

- Smaller populations yield fewer fish per unit of effort.

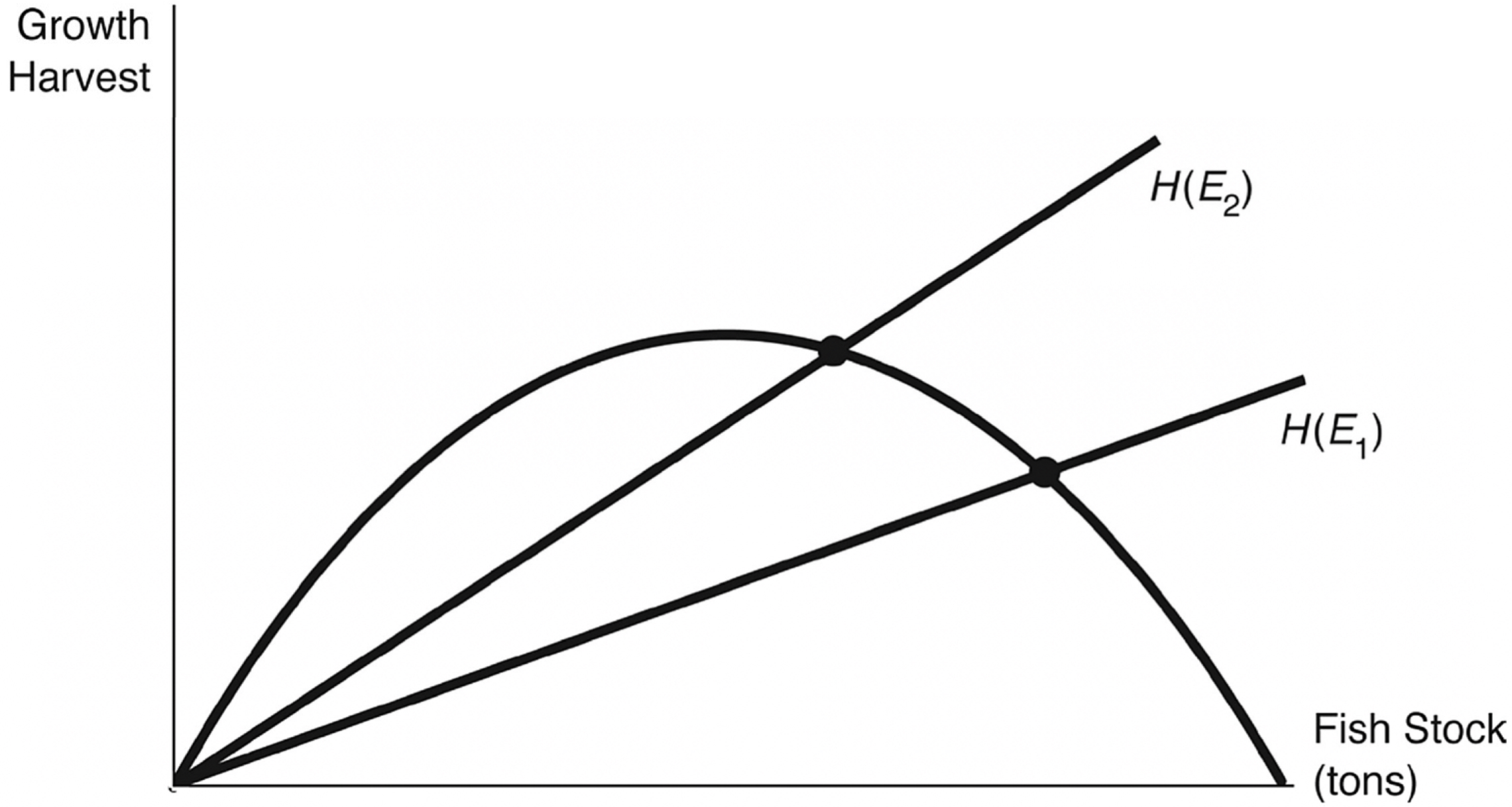

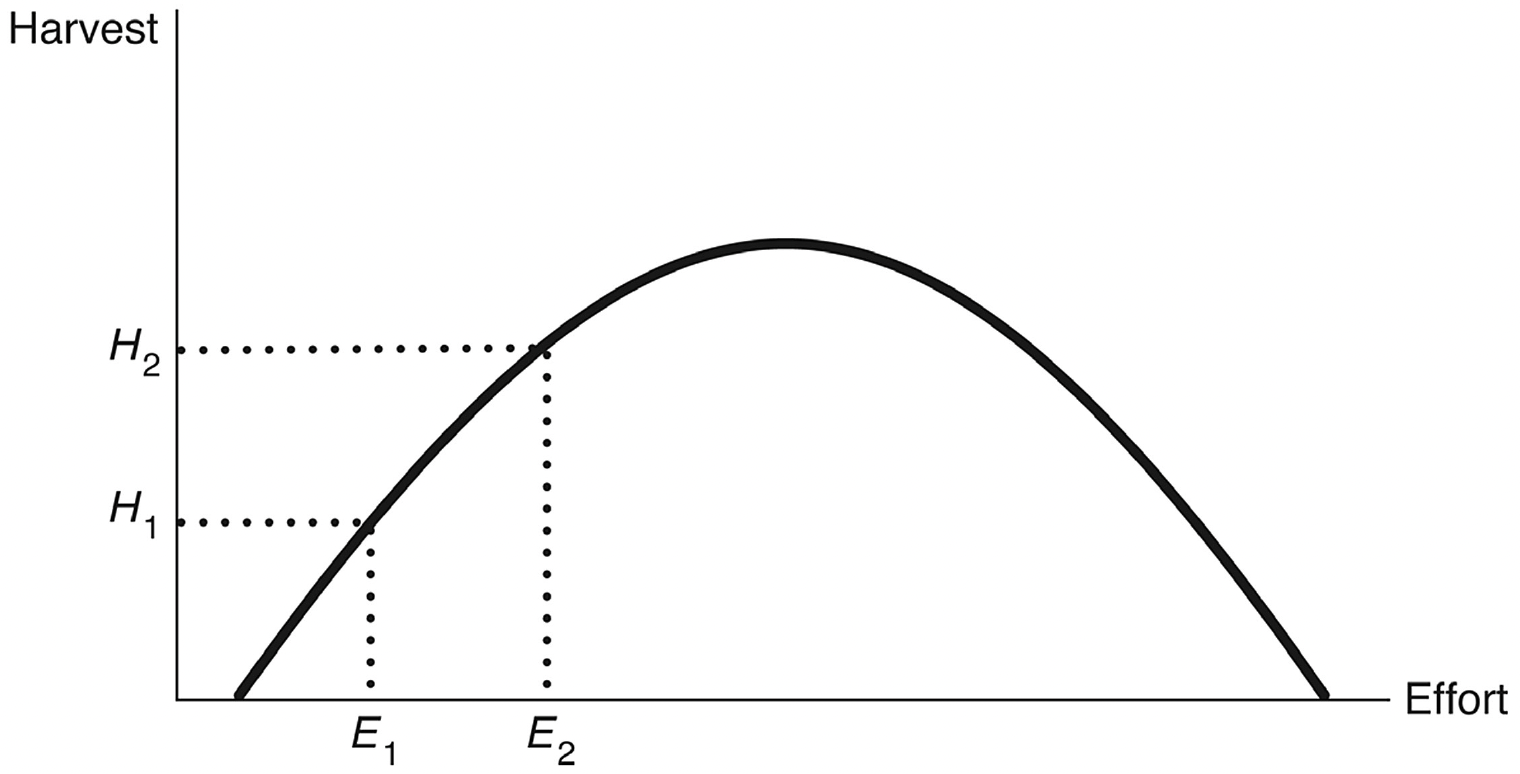

Harvest-Effort Functions

- Relationship between Catch and Effort:

- Increasing effort rotates the harvest function.

- Sustainable yield is at the intersection with the growth function.

Sustainable Yield Function

- Effort vs. Sustainable Yield:

- Shows the sustained yield associated with different levels of fishing effort.

- Increasing effort initially increases yield, then decreases it after a point.

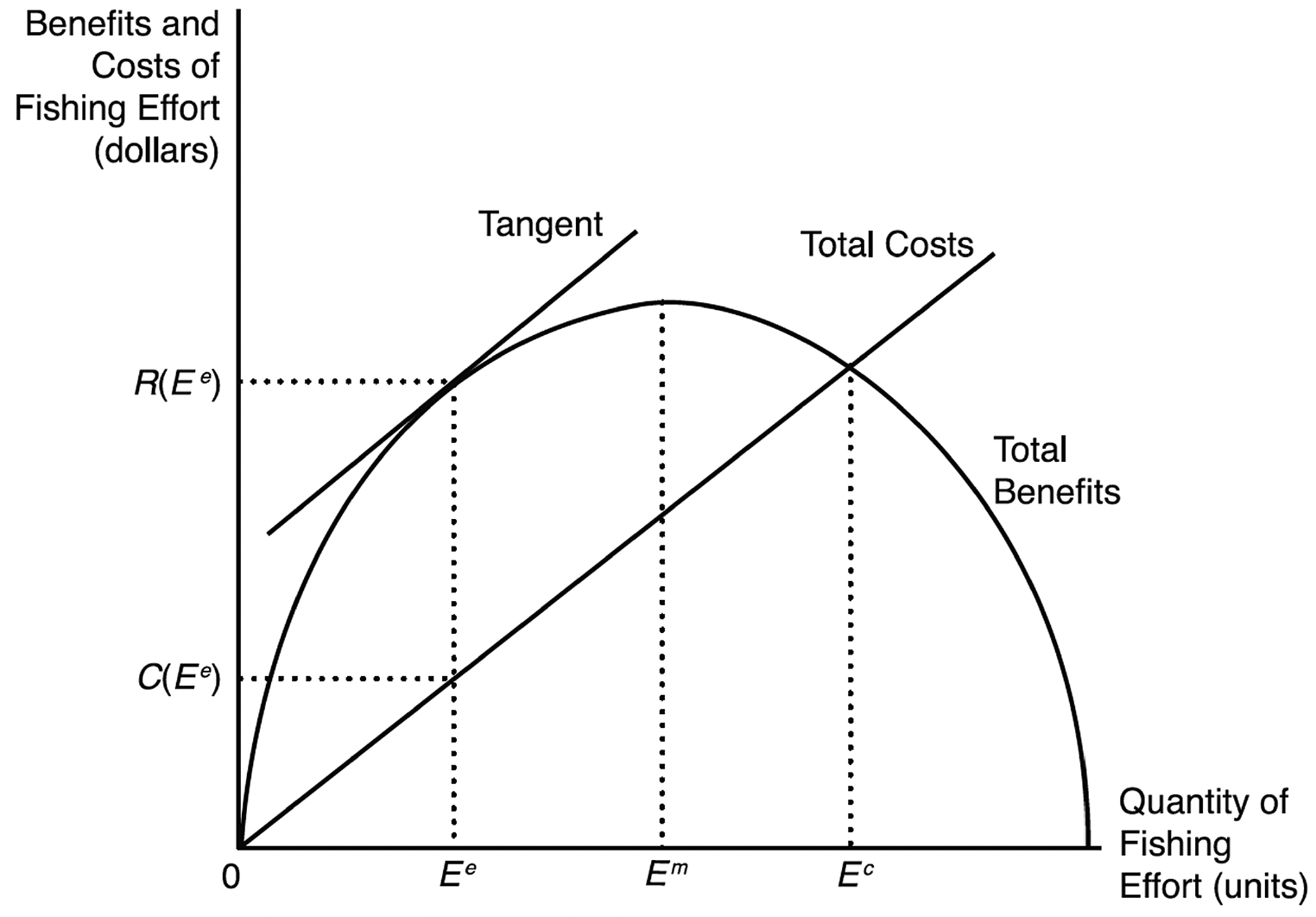

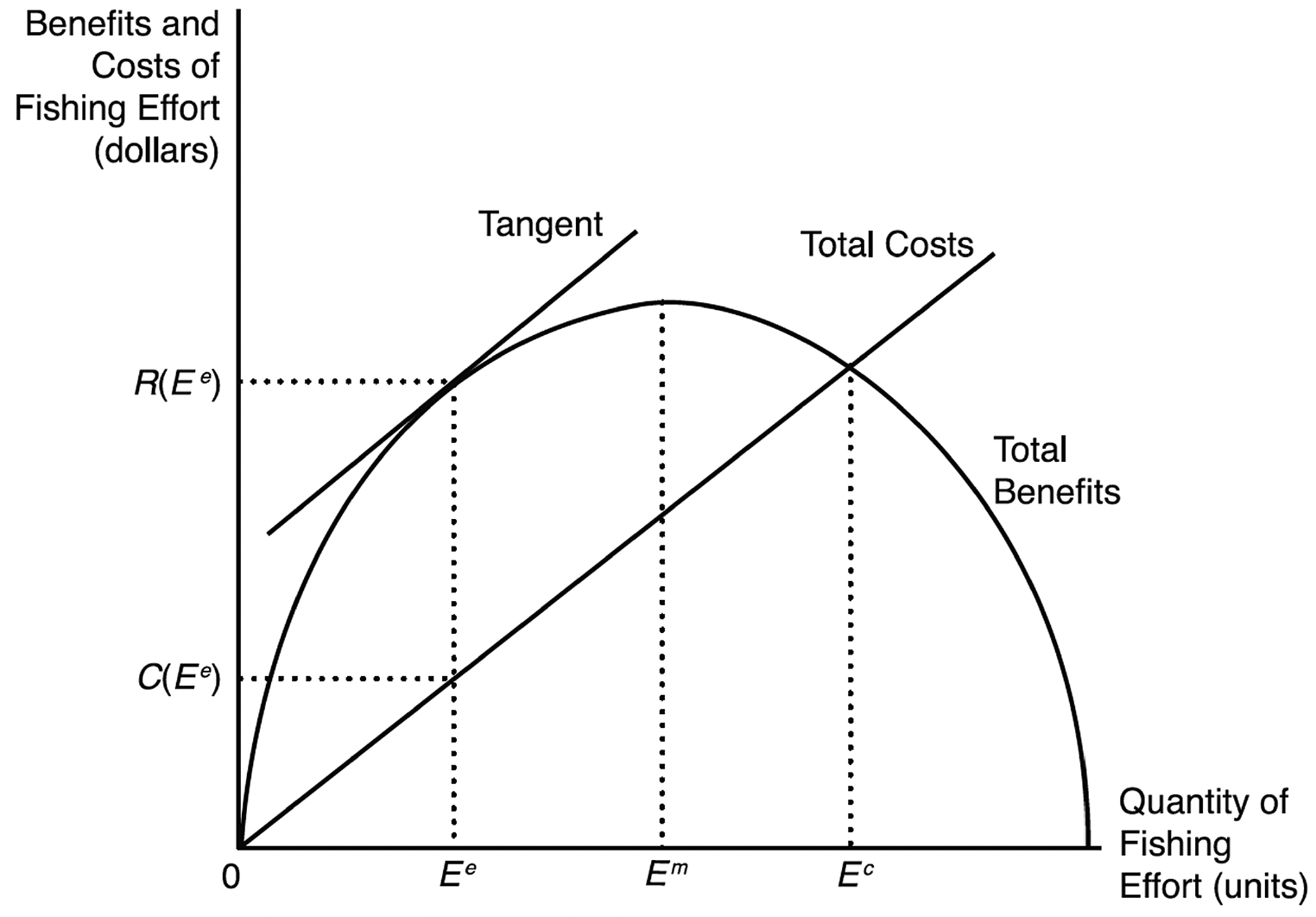

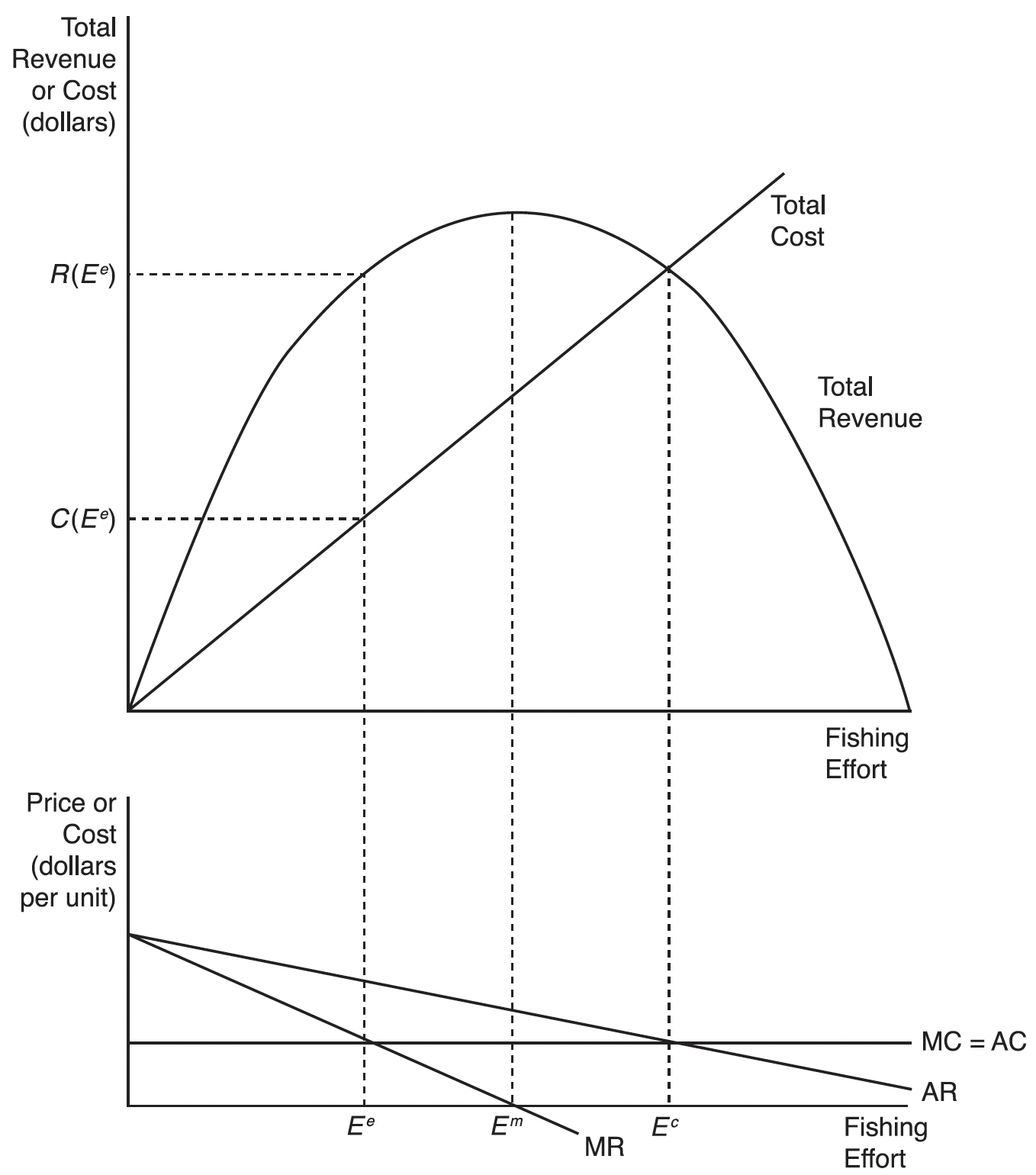

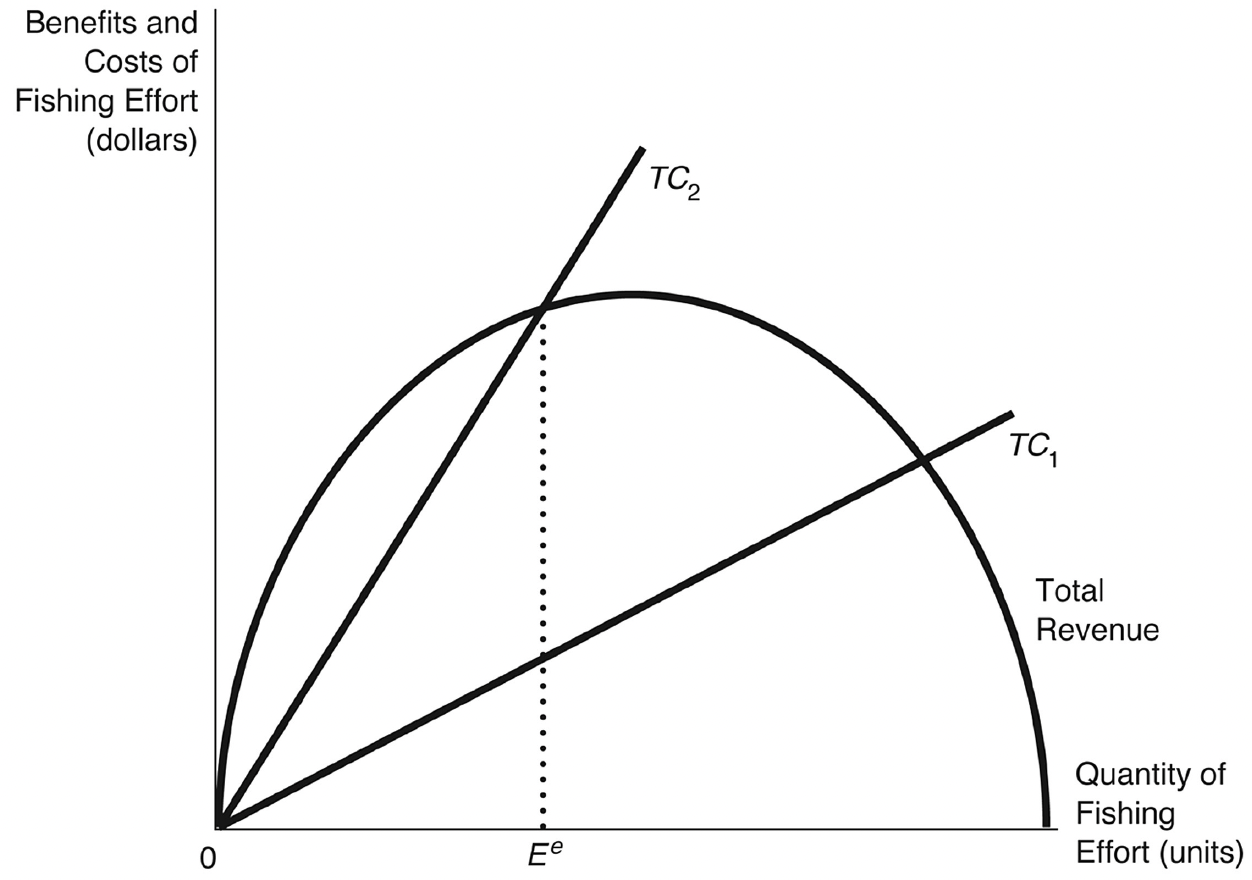

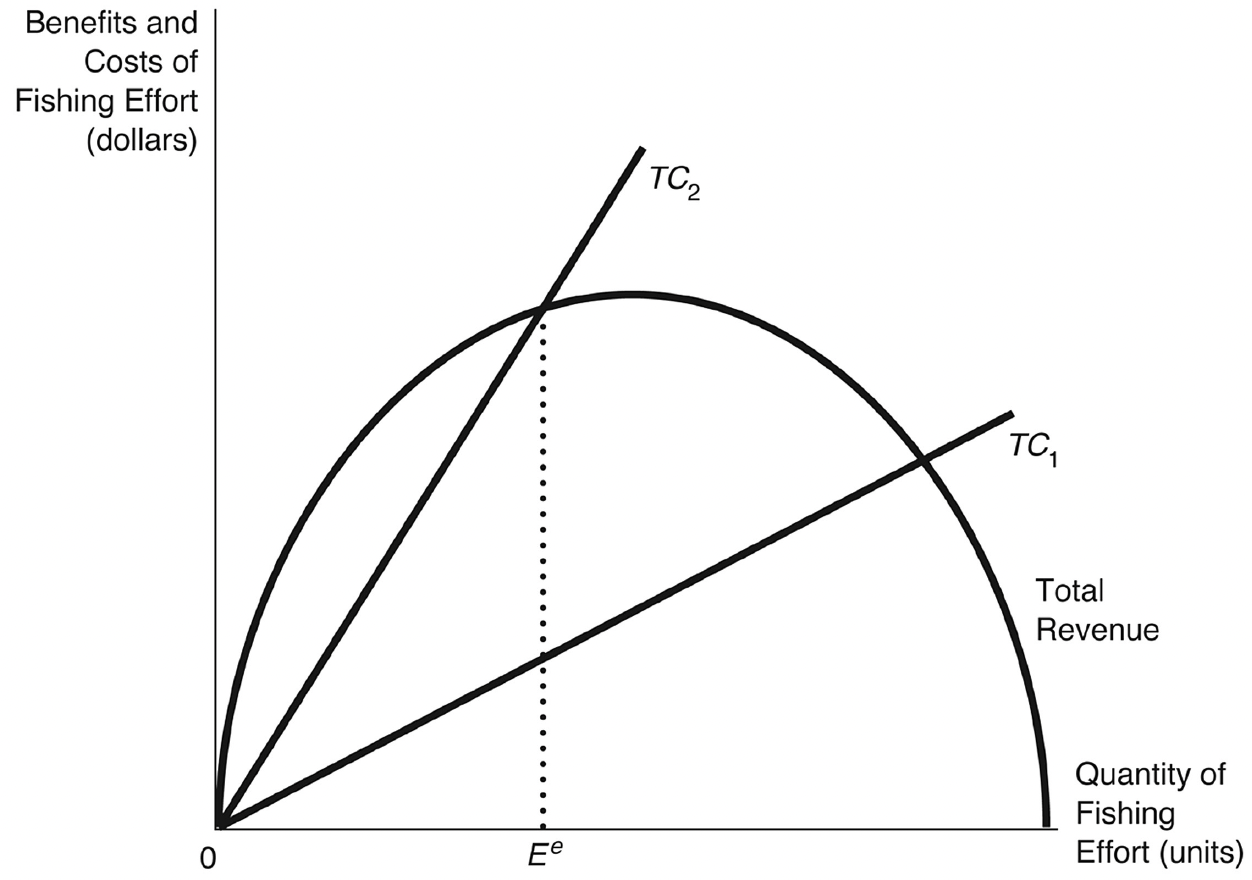

Determining Efficient Level of Effort

Total Revenue (\(TR\)):

- \(TR\) = Price × Quantity Caught.

Total Cost (\(TC\)):

- \(TC\) = Marginal Cost of Effort × Units of Effort.

Efficient Effort Level (\(E^{e}\)):

- Where the difference between \(TR\) and \(TC\) is maximized.

- Marginal Benefit equals Marginal Cost.

Impact of Technological Change

- Effect on Efficient Effort Level:

- Technological improvements lower marginal costs (e.g., better sonar detection).

- Results in increased effort, lower population size, larger annual catch, and higher net benefits.

Market Allocation in a Fishery

- Sole Owner vs. Open Access:

- Sole Owner: Maximizes profit by choosing efficient effort level (\(E^{e}\)).

- Open Access: Leads to overexploitation, effort level increases to where profits are zero (\(E^{c}\)), creating the external costs:

- External Costs:

- Contemporaneous External Cost: Overcommitment of resources, reducing current profits.

- Intergenerational External Cost: Overfishing reduces stock, lowering future profits.

Example: Harbor Gangs of Maine and Other Informal Arrangements

- Informal Arrangements:

- Fishers form “gangs” to restrict access to fishing areas.

- Enforce territories to prevent overexploitation.

- Benefits:

- Higher catch per trap.

- Larger lobsters, fetching higher prices.

- Success Factors:

- Strong leadership.

- Social cohesion.

- Complementary incentives like individual quotas.

Public Policy toward Fisheries

- Policy Responses:

- Raising the real cost of fishing.

- Implementing taxes on effort or catch.

- Reducing or eliminating harmful subsidies.

- Establishing catch share programs.

Public Policy toward Fisheries

Raising the Real Cost of Fishing

- Early Policies:

- Banning efficient gear (e.g., barricades, traps, thinner monofilament nets, gill netters).

- Limiting fishing times and areas.

- Achieving yield corresponding to the efficient effort level (\(E^{e}\))

- Inefficiency Resulted:

- Increased real resource costs, involving utilization of resources.

- Overcapitalization in fishing fleets.

- Substantial loss in the fishers’ net benefit.

Public Policy toward Fisheries

Taxes as a Policy Tool

- Implementing Taxes:

- Tax on fishing effort (or catch).

- Increases cost to fishers, reducing effort.

- Advantages:

- Encourages cost-effective fishing methods.

- Government collects tax revenues.

- Net benefits retained by society.

Public Policy toward Fisheries

Perverse Incentives: Subsidies

- Negative Impact of Subsidies:

- Reduce operating costs (e.g., fuel), encouraging overfishing.

- Lead to overexploited stocks and illegal fishing.

- Global Fisheries Subsidies:

- Governments spend about $35 billion per year.

- Equivalent to 20% of the value of global marine capture.

- WTO Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies (2022):

- Prohibits harmful fishing subsidies.

- Targets IUU (illegal, unreported, or unregulated) fishing and overfished stocks.

- Provides technical assistance to developing countries.

Catch Share Programs

- Definition:

- Allocate a portion of the total allowable catch (TAC) to individuals, communities, or cooperatives.

- Types of Programs:

- Individual Fishing Quotas (IFQs).

- Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs).

- Territorial Use Rights Fisheries (TURFs).

- Fishing Cooperatives.

- Community Fishing Quotas.

- Global Adoption:

- Nearly 200 programs in 40 countries.

- Cover more than 500 species.

Catch Share Programs

Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs)

- Key Characteristics:

- Quotas specify a share of the total catch.

- Total quotas equal the efficient catch level.

- Quotas are freely transferable among fishers.

- Advantages:

- Encourage efficiency and cost-effective methods.

- Align individual incentives with sustainability.

- Promote technological innovation.

Practical Challenges in ITQ Implementation

Bycatch Issues

- Definition: Bycatch refers to unintended species caught during fishing.

- Some fishers may not have sufficient ITQs to cover the bycatch

- Dumping bycatch results in a double waste:

- Wasted harvests: Jettisoned fish are not likely to survive

- Smaller stocks

High-Grading Concerns

- Definition: High-grading occurs when quotas are based on weight, but the value of the catch depends on the size of individual fish.

- Fishers may discard smaller fish to make room for larger, more valuable ones, even if smaller fish meet the quota.

- Impacts:

- Leads to double waste.

ITQ vs. Traditional Size and Effort Restrictions

Example: Atlantic Sea Scallop Fishery

- Management Approaches:

- Canada: Implemented ITQ system.

- United States: Used traditional size and effort restrictions.

- Canada:

- Maintained higher stock abundance.

- Increased revenue per sea-day.

- Fishery revenue increased due to higher catch per effort.

- United States:

- Declined stock abundance.

- Decreased revenue per sea-day.

- Harvesting of undersized scallops.

Effectiveness of ITQs in Fisheries Management

Global Study on Fisheries

- Scope: Analyzed over 11,000 fisheries globally from 1950 to 2003.

- Key Findings:

- Fisheries with catch share rules (e.g., ITQs) experienced much less frequent collapse.

- By 2003, the fraction of collapsed ITQ fisheries was half that of non-ITQ fisheries.

Additional Study on ITQs

- Scope: Examined 20 fish stocks post-ITQ implementation.

- Key Findings:

- 12 stocks showed improvement in size.

- 8 stocks continued to decline.

- ITQs can sometimes help but are not a universal solution.

ITQs or TURFs? Species, Space, or Both?

Advantages and Challenges of ITQs

- Advantages:

- Popular and species-based, fostering efficient harvesting and conservation incentives.

- Assures a sustainable total allowable catch (TAC).

- Challenges:

- Enforcement difficulties.

- Externalities:

- Gear impacts on ecosystems.

- Spatial and cross-species externalities, which can increase under ITQs.

- Competition over timing of harvest:

- Productive periods may increase external costs (e.g., bycatch, juvenile stock impact).

- Coase theorem limitation:

- High transaction costs hinder solving remaining externalities through ownership rights.

ITQs or TURFs? Species, Space, or Both?

Advantages and Challenges of TURFs

- Advantages:

- Solves issues of time and space management.

- Protects sensitive areas and habitats.

- Facilitates management of interspecies interactions and habitat conservation.

- Challenges:

- Conflict and coordination problems within local cooperatives.

- Scale mismatch: TURFs may not align with the natural range or habitat of the species being managed.

ITQs or TURFs? Species, Space, or Both?

When to Use ITQs or TURFs

ITQs

- Effective for marine fisheries.

- Suitable for large-scale, species-based management.

TURFs

- Advantageous in developing countries with weak institutional structures.

- Most appropriate for small, local populations or specific areas.

- No one-size-fits-all solution:

- Each method has a niche depending on the context, species, and institutional capacity.

- Combining ITQs and TURFs may optimize fisheries management in some scenarios.

Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs)

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea:

- Grants countries rights up to 200 miles offshore.

- Significance:

- Enables national management and enforcement.

- Protects coastal resources.

- Limitations:

- Highly migratory species remain unprotected.

- Open oceans (high seas) still face overexploitation.

Russia’s “Peanut Hole”

- Location: A high seas area in the center of the Sea of Okhotsk, surrounded by Russia’s EEZ.

- Significance:

- Previously a global commons outside Russia’s jurisdiction.

- Known as the “Peanut Hole” due to its unique shape.

- Challenges:

- Overfishing by international fleets posed threats to fish stocks.

- Difficulty in coordinating sustainable management of resources in this area.

- Resolution:

- In 2014, Russia gained control of the “Peanut Hole” under UN Convention on LOS (Law of the Sea) provisions, integrating it into its EEZ.

Marine Protected Areas and Marine Reserves

Motivation: Challenges of Regulating Only Catch

- Unregulated factors:

- Type of gear used and harvest locations.

- Environmental impacts:

- Damaging gear affects targeted species (e.g., capturing unsellable juveniles) and non-targeted species (bycatch).

- Harvesting in sensitive areas (e.g., spawning grounds) can harm sustainability.

What Are MPAs and Marine Reserves?

- Marine Protected Areas (MPAs):

- Defined as areas reserved to protect natural and cultural resources.

- Protection levels range from minimal to full.

- Marine Reserves:

- A subset of MPAs with full protection (e.g., no harvesting, high protection from threats like pollution).

MPAs and Marine Reserves

Benefits

- Species Protection: Prevent harvest within reserve boundaries.

- Habitat Preservation: Reduce damage caused by harmful fishing practices.

- Ecosystem Balance: Protect pivotal species to maintain biodiversity and productivity.

- Spillover Benefits:

- Larger populations lead to increased catches outside reserve boundaries.

- Example: Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument showed spillover benefits for tuna species.

MPAs and Marine Reserves

Challenges

- Short-term Costs:

- Harvesters face immediate reductions in fishing areas.

- Delayed benefits impose costs (e.g., interest on loans).

- Political Opposition:

- Harvesters who do not perceive benefits may resist reserve proposals.

- Present Value Considerations:

- Benefits must be large and timely enough to offset short-term costs.

MPAs and Marine Reserves

International Efforts and Innovations

- Global Initiatives:

- The Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) aims to conserve 10% of marine ecoregions.

- Eco-labeling Incentives:

- Link seafood certification (e.g., Marine Stewardship Council) to adjacent MPAs.

- Proposal: Use “sustainability credits” to protect fish stocks and encourage sustainable practices.

Commercially Valuable Fisheries

Conclusion

- Overfishing is a Global Issue:

- Leads to significant economic and ecological losses.

- Efficient Management is Essential:

- Requires appropriate policies and institutions.

- Market-Based Solutions:

- ITQs, TURFs, and catch share programs show promise.

- Align economic incentives with conservation.

- International Cooperation:

- Critical for managing shared and migratory stocks.

- Agreements like the WTO’s fisheries subsidies agreement are steps forward.