Week 5

Common Property Resources

In Week 5, we will sum up the Property Right and the Environment, and then move to discussion on how to property manage common pool resources.

🏫 Lecture Slides

Lecture 5 - Property Rights, the Coase Theorem, and the Environment

View SlidesLecture 6 - Common Property, Open Access, and Property Rights

View Slides

🎥 Looking for lecture recordings? You can only find those on Brightspace.

✍️ Classwork

- Classwork 3: Property Rights, the Coase Theorem, and the Environment

📄 View Classwork

📝 Homework

🏡 Homework 1 has been posted. 🏡

📚 Recommended Reading

Alternative Property-Right Structures and the Incentives They Create

Private ownership is only one way to assign rights to use resources. Other arrangements include:

- State-property regimes: the government holds title and controls access and use.

- Common-property regimes: a defined community jointly owns and manages the resource.

- Res nullius / open-access regimes: no party holds ownership or control over access.

Each arrangement shapes user behavior—and therefore resource outcomes—in different ways.

State property exists, to some extent, in nearly every nation. National parks and wilderness areas are common examples. These systems can face efficiency problems when the goals or incentives of officials who design or enforce the rules do not align with society’s broader interests.

Common property refers to shared resources governed collectively rather than by individual private owners. Rights to use may be formal (spelled out in law) or informal (rooted in custom or tradition). How well common-property systems perform—both economically and ecologically—depends on the quality of collectively chosen rules and on compliance with those rules. Although there are notable success stories, breakdowns are, unfortunately, even more frequent. Successful cases often rest on reciprocity and trust within the user group.

A well-known success is Switzerland’s alpine grazing system. While farmland is typically private, grazing rights on Alpine meadows have long been managed as common property. An association of users sets specific limits on livestock to deter overgrazing. Membership has historically been stable, with rights and responsibilities passing down through families. That continuity supported trust and reciprocal behavior, which in turn sustained compliance and the rules’ effectiveness.

Such stability is not guaranteed, especially under rising population pressure. In Mawelle, Sri Lanka, villagers initially created a sophisticated rotating system of fishing rights to distribute access to prime locations and times while protecting the stock. Over time, population growth and the entry of outsiders both increased demand and eroded cohesion and trust. The customary rules became unenforceable, leading predictably to overuse of the fishery and lower incomes.

Res nullius (open access) resources, by definition, lack a mechanism to control entry because no person or group has the legal authority to do so. Consequently, use proceeds on a first-come, first-served basis. Such open-access settings underpin what is commonly called the “tragedy of the open-access commons.”

Open-access common-pool resources are shared stocks that are nonexclusive (anyone can exploit them) and rivalous (one user’s harvest reduces what’s left for others). The American bison illustrates the consequences. In the early United States, bison were so abundant that unrestricted hunting posed no immediate problem: people could readily obtain hides and meat, and one hunter’s aggressiveness did not meaningfully raise the time and effort others needed. When scarcity was absent, open access did not undermine efficiency. As demand rose and the herd shrank, however, each incremental unit of hunting effort required more time and work to achieve an extra harvest.

Bison Harvesting

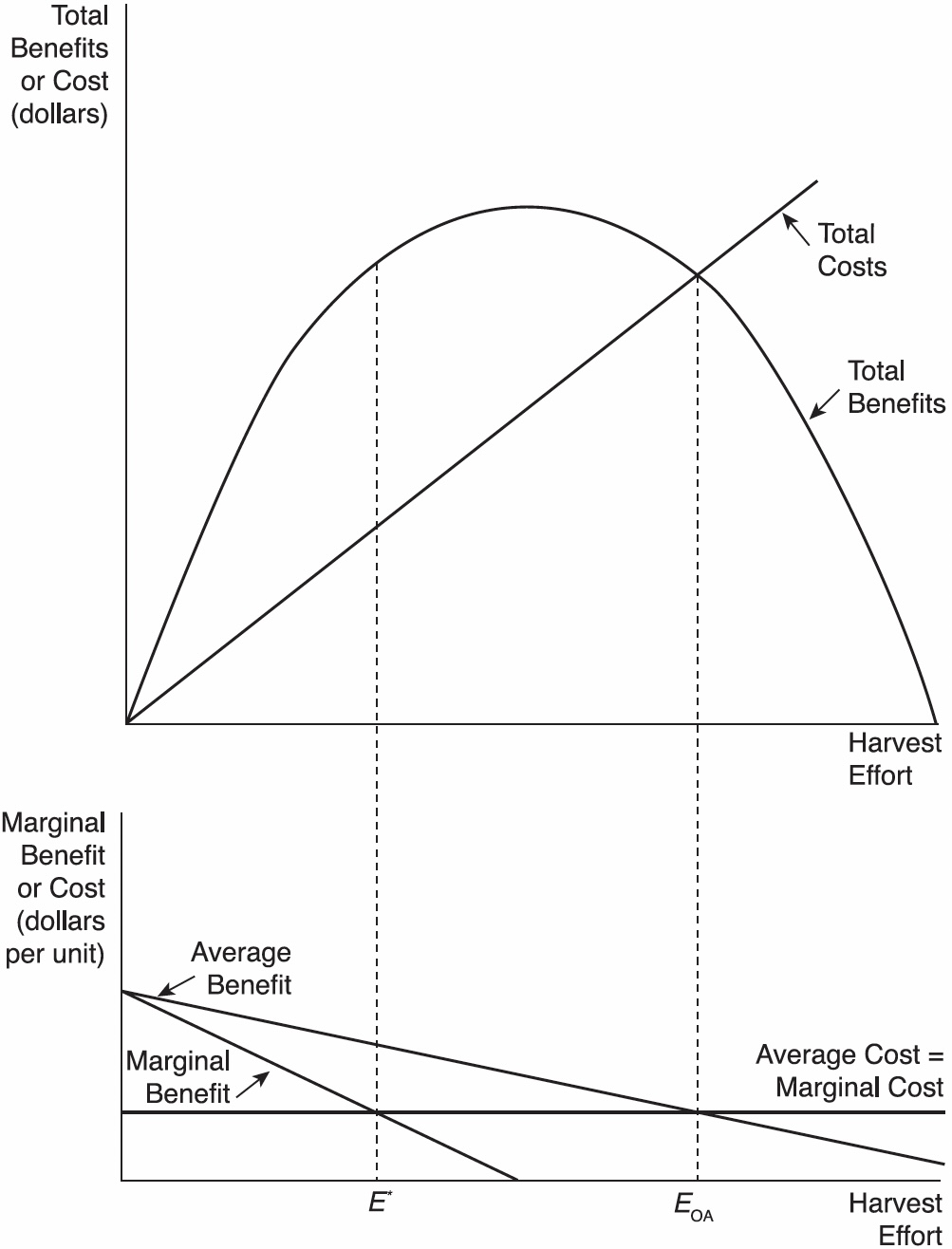

A graphical analysis clarifies how different property-rights regimes (and the harvest levels they induce) affect economic surplus (benefits to consumers and producers net of costs). In the top panel, total revenue equals the (assumed constant) bison price times harvested quantity at each effort level; the upward-sloping total cost curve reflects higher total costs as effort increases (with constant marginal cost in this example). The total surplus at any effort is the vertical gap between the total revenue and total cost curves.

In the bottom panel, the marginal revenue curve slopes downward—even though price is constant—because greater effort reduces the population, which lowers harvest per unit of effort. The efficient effort level, \(E^{*}\), maximizes surplus. That can be seen two equivalent ways: (1) in totals, \(E^{*}\) maximizes the distance between total benefits and total costs; (2) in margins, \(E^{*}\) occurs where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, with marginal cost capturing the extra cost of the last unit of effort. The lower-panel curves are derived from the relationships shown in the upper panel.

Under open access, unrestricted entry makes the outcome inefficient. Individual hunters lack an incentive to restrain effort to protect the shared surplus. Instead, they continue to harvest until total benefits equal total costs—the open-access effort \(E_{OA}\). Overuse occurs because individuals cannot appropriate the surplus; additional effort dissipates it. Losses that could be avoided by an exclusive owner—or by effective collective governance—are not avoided when access is free.

Two general features of the open-access outcome follow:

- With sufficiently high demand, overexploitation is the result.

- The surplus is dissipated: no one captures it, and it disappears.

The mechanism is straightforward: unlimited access removes the incentive to conserve. An owner able to exclude others has reason to maintain the herd at an efficient size to preserve surplus, which also reduces the time and effort needed per unit of harvest. By contrast, an open-access hunter gains little from self-restraint because any surplus preserved would be partly taken by others who keep harvesting. Hence, when resources are scarce, open access leads to inefficient allocation. In combination with habitat conversion to farms and pasture, this dynamic drove the Great Plains bison herds to the brink of extinction.

Community-Devised Governance of the Commons (Ostrom’s Insights)

An alternative to relying on private ownership or top-down regulation is for resource users to craft their own agreements to avoid the tragedy of the commons. Elinor Ostrom, who received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economics, documented how many communities govern shared resources through self-organized, cooperative arrangements without privatization or heavy state control. Local users often possess context-specific knowledge—about ecology, seasons, and customs—that regulators may lack when setting access fees or harvest limits. They also understand that short-run individual gain can trigger long-run ecological and economic collapse, so they adopt precautionary rules to sustain the resource.

Cooperative local management tends to work when most users participate in designing the rules; when monitoring is conducted by people accountable to users who regularly assess conditions and compliance; when disputes can be resolved quickly and inexpensively; when rules are adapted to local ecology, culture, and technology; and when sanctions are graduated, starting modestly and escalating for repeated violations.

Ostrom’s approach can complement government rather than replace it, especially for large-scale commons where layered institutions are helpful. A state or federal agency might administer and enforce an individual transferable quota program, while local fishers co-design allocation rules and handle day-to-day conflicts. The broader lesson is that effective resource governance is participatory, combining local (including Indigenous) knowledge, history, and culture with wider legal and scientific capacity. At national or global scales, government involvement is usually essential, but policies should still respect local variation and incorporate community voices.

References

Tietenberg T. and Lewis L., Chapter 2. The Economic Approach: Property Rights, Externalities, and Environmental Problems, Environmental and Natural Resource Economics (12th Edition)

Harris J. and Roach B., Chapter 3. Theory of Environmental Externality, Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach (5th Edition)

⚠️ Note: These contents from the above book chapter are shared under fair use for educational purposes to support your learning.

💬 Discussion

Welcome to our Week 5 Discussion Board! 👋

This space is designed for you to engage with your classmates about the material covered in Week 5.

Whether you are looking to delve deeper into the content, share insights, or have questions about the content, this is the perfect place for you.

If you have any specific questions for Byeong-Hak (@bcecon) or peer classmate (@GitHub-Username) regarding the Week 5 materials or need clarification on any points, don’t hesitate to ask here.

Let’s collaborate and learn from each other!